We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

The Final Battle in Revelation

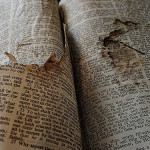

I will conclude this series on the violent imagery in Revelation by addressing the infamous eschatological battle scene found in 19:11-21, for it is this graphically violent section of Revelation that is most frequently appealed to by those who argue against the claim that Jesus reveals an enemy-loving, non-violent God that is unconditionally opposed to violence. (You can find part 1 of this series here, part 2 here, and part 3 here.)

Revelation 19 begins, not with an army preparing for battle, but with an army celebrating God’s victory in a battle that has already been fought (19:1-4). The inhabitants of heaven proclaim the truth that God has already defeated the prostitute (representing “the arrogance of the earthly power”) and has thereby already avenged the shed blood of his servants (19:1-4).

The only thing resembling a battle is one regarding the truth of the Lamb’s victory, known by the inhabitants of heaven (as we discussed in Part 3 of this series), to once-and-for-all vanquish the demonic deception that continues to oppress the inhabitants of the earth. The irony is that, while Revelation 19 is frequently appealed to as the clearest example of Jesus engaging in literal violence, in reality it does not depict a single violent act.

John utilizes traditional warfare imagery to imaginatively express this final battle between truth and deception, but, as usual, he completely transforms this imagery in the process. To cite one example, John applies to Jesus Isaiah’s macabre vision of Yahweh as a warrior wearing robes that are covered with blood (Isa 63:1-3; Rev. 19:13). In Isaiah’s vision, however, Yahweh is stained with the blood of his enemies whom he has trampled like grapes in a winepress in his “day of vengeance.” By contrast, Jesus’ robes are blood stained before he goes into battle, and the stains are from his own spilled blood as well as the blood of his martyred servants. It represents, once again, that Christ and his followers win by having their own blood shed rather than by shedding the blood of others.

Also in keeping with traditional apocalyptic symbolism, John depicts Christ wielding a “sharp sword” to “strike down the nations” (19:15). But it is extremely important to notice that the sword that Jesus wields comes out of his mouth (Rev. 19:15, 21; cf. 1:16; 2:26; 3:26). His weapon, clearly, is nothing other than the truth he speaks, which is why the title he rides into battle with is “Faithful and True” (19:11).

Finally, a word should be said about John’s lurid depiction of Jesus on a white horse “treading on the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty” (19:15). This is not John’s first use of this winepress imagery. The “great winepress of God’s wrath” is first mentioned in chapter 14 (vv. 19-20), and in this context John has significantly nuanced the details of the traditional imagery (See Is 63). While the traditional imagery depicts sinners being crushed like grapes because of their wickedness, John here depicts grapes being crushed simply because they are ready to be harvested (vv. 15,18). Moreover, while the traditional imagery identifies God’s judgment with the crushing of wicked grapes, John identifies God’s judgment with people drinking the wine that is formed from ripened crushed grapes (v.10). The crushed grapes express the wrath of God not because they are crushed, but because they form “the wine of God’s fury, which has been poured full strength into the cup of his wrath” (14:10; cf. 14: 8-9; 16:6; 17:6). God’s wrath is thus directed not toward the grapes, as it is in the traditional use of this imagery, but toward the unrepentant who are made to drink the wine that is a by-product of these grapes being crushed.

When we put this together with John’s pervasive theme that believers overcome by their willingness to be martyred, it suggests that the blood that flows from the winepress of God’s fury is not the blood of God’s enemies, but the blood of his servants whom these enemies murdered.

John’s use of the traditional winepress imagery provides yet another stunning example of how John turns violent imagery on its head by radically reinterpreting it through the lens of the self-sacrificial Lamb. Followers of the Lamb are called to participate in the war and to share in the victory of the Lamb, and we are called to do it the way the Lamb himself did it; namely, by choosing to love our enemies and suffer at their hands rather than to take up arms against them.

To conclude, John’s revision of traditional warfare imagery, with its stunning reassessment of power, “is so contrary to normal human practice that most churches throughout history have not agreed with John…”[1] I suspect that this is at least part of the reason why the genius of John’s transformation of violent imagery and the beauty of his non-violent, self-sacrificial message, have so rarely been grasped throughout history. To this day, it seems, the majority of Christians are more comfortable with a militant Messiah who slays our enemies than they are with a loving Messiah who would rather die out of love for his enemies and who calls us to do the same. For Christ’s sake and for the future of his church, one can only pray that the heart of this faith-professing majority would begin to change.

[1] S. Friesen, Imperial Cults and the Apocalypse of John: Reading Revelation in the Ruins (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 216.

Photo credit: Lawrence OP via Visual hunt / CC BY-NC-ND

Related Reading

Old Testament Support for the Warfare Worldview

Rebuking Hostile Waters Satan plays a minor role in the Old Testament relative to the New Testament. Instead, the warfare worldview in the Old Testament is expressed in terms of God’s conflict with hostile waters, cosmic monsters, and other gods.Like their Ancient Near Eastern neighbors, ancient Jews believed that the earth was founded upon and…

The Longing of Advent

The Advent season is a time of anticipating the coming of God, in Christ, a time of turning our imagination toward the revelation of God’s love for us. This after all is the deepest longing of our heart, and our natural longings always point us to something real. We grow hungry only because there’s such…

Does the Old Testament Justify “Just War”?

Since the time of Augustine, Christians have consistently appealed to the violent strand of the Old Testament to justify waging wars when they believed their cause was “just.” (This is Augustine’s famous “just war” theory.) Two things may be said about this. First, the appeal to the OT to justify Christians fighting in “just” wars…

The Politics of Jesus, Part 2

Even in the midst of politically-troubled times, we are called to preserve the radical uniqueness of the kingdom. This, after all, is what Jesus did as he engaged the first century world with a different kind of politics (see post). To appreciate the importance of preserving this distinction, we need to understand that the Jewish…

Part 2: Disarming Flood’s Case Against Biblical Infallibility

Image by humancarbine via Flickr In this second part of my review of Disarming Scripture I will begin to address its strengths and weakness. [Click here for Part 1] There is a great deal in Disarming Scripture that I appreciate. Perhaps the most significant thing is that Flood fully grasps, and effectively communicates, the truth that…

Reflecting on the Lord’s Prayer

Jesus begins the instruction on prayer (Matthew 6:9-13) by telling his disciples to pray for the Father’s name to be “hallowed,” for his kingdom to come, and for his will to be established on earth as it is in heaven. He is, in effect, telling them to pray for the fulfillment of everything his ministry,…