We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Redefining Transcendence

God is transcendent, which basically means that God is “other” than creation. The problem is that classical thinking about God’s “otherness” has been limited to what reason can discern about God. As a result, all that can be said about his transcendence is what God is not. We are thus unable to acquire a positive conception of a wholly simple, purely actual, immutable, timeless, limitless, perfect being that exists, not over-and-against the world as a particular deity, but as the cause and “transcendental unity” of all existing things in the world. As such, there is a kind of agnosticism about this view of because we are unable to say anything concrete or positive about who God is.

By relying heavily on the negative approach of Hellenistic philosophy, the classical tradition ended up defining God’s transcendence over-and-against revelation, which is why this tradition assumed the revelation of God in Christ and in Scripture had nothing to say about the nature of God’s transcendent attributes that reason couldn’t discern on its own. It is claimed that revelation is also bound to the finite categories of human thinking and speaking, and therefore “revelation does not tell us what God is.” Instead, it simply “joins us to him as if to an unknown…”[1]

By limiting itself to what reason can discern about what God is not, classical theology failed to explore the even more mysterious, and the much more beautiful, “otherness” of what God reveals himself to be.

I argue that the “otherness” of God is only properly exalted, and God’s self-revelation on the cross is only properly honored, when God’s transcendence is most fundamentally defined by means of what is revealed in the crucified Christ rather than in contrast to what is revealed in the crucified Christ.

Could anything be more incomprehensible and more exalting of God’s mysterious “otherness” than the depth of love that motivated the Son to set aside the bliss of his communion with the Father and Spirit and to dive into the self-created hell of a race of rebels? Could any mere philosophical negation be more mysterious than the God who manifested his greatness by becoming a microscopic zygote in the womb of an unwed Jewish peasant girl? And could there be any greater indicator of the unfathomable nature of God’s transcendence than the fact that God’s holiness was most perfectly displayed when God became our sin (2 Cor 5:21) or the fact that God’s perfect loving unity was most perfectly displayed when God experienced our God-forsakenness (Gal 3:13)?

While God’s transcendence is certainly incomprehensible, I submit that God’s ability and loving willingness to radically change for us — to the point of becoming that which he is not when he hung on the cross — is even more beautifully unfathomable and even more exalting of God’s “otherness.” While God’s eternal character and being are certainly mysterious, I contend that God’s ability and loving willingness to nevertheless be deeply impacted and moved by us, and even to suffer hell on our behalf, is even more beautifully mysterious and exalting of God.

In short, my argument is that the transcendent moral character of God revealed in the crucified Christ and witnessed to in biblical depictions of God being in sequence with us, changing plans in response to us, and being impacted and moved by us, should be regarded as more fundamental to our appreciation of God’s transcendence than the metaphysical transcendence of God that can be discerned by reason.

God becoming human and suffering on the cross do not compromise divine transcendence. To the contrary, depictions of God along these lines reflect the kind of incomprehensibly loving divine transcendence that is revealed in the crucified Christ.

[1] Aquinas, Summa Contra Gentiles, Q 12, art. 13, 136.

Category: General

Tags: Classical Theism, Cruciform Theology, Revelation

Topics: Attributes and Character

Related Reading

Does God Have a Dark Side?

In the previous post, I argued that we ought to allow the incarnate and crucified Christ to redefine God for us rather than assume we know God ahead of time and then attempt to superimpose this understanding of God onto Christ. When we do this, I’ve argued, we arrive at the understanding that the essence…

What to Do If You See God as Violent

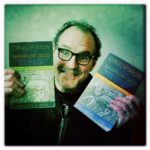

God really is as beautiful as he is revealed to be on Calvary. Communicating this is my goal in everything I write—especially Crucifixion of the Warrior God and Cross Vision. But for many, to see him as being that loving, is not easy. We have to make a concerted effort for our brains to adjust…

How to Interpret the Law of the Old Testament

While there are multitudes of passages in the OT that reflect an awareness that people are too sinful to be rightly related to God on the basis of the law, there is a strand that runs throughout the OT that depicts Yahweh as “law-oriented.” This label is warranted, I believe, in light of the fact…

Cross Centered Q&A

For those within driving distance of Saint Paul, MN, we invite you to join us for a free event. Greg will be discussing his new book Crucifixion of the Warrior God with Bruxy Cavey (Pastor of The Meeting House in Toronto) and Dennis Edwards (Pastor of Sanctuary Covenant Church in Minneapolis). Don’t miss this opportunity to hear Greg…

The Starting Point for “Knowing God”

While it makes sense that Hellenistic philosophers embraced knowledge of God as the simple, necessary and immutable One in an attempt to explain the ever-changing, composite, contingent world (see post here for what this means), it is misguided for Christian theology to do so. By defining knowledge of God’s essence over-and-against creation, we are defining God’s essence…

A Cruciform Dialectic

One of the most important aspects of God’s action on Calvary, I believe, is this: God revealed himself not just by acting toward humans, but by allowing himself to be acted on by humans as well as the fallen Powers. God certainly took the initiative in devising the plan of salvation that included the Son…