We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

An Alternative to Biblical Inerrancy

As with all other theological issues, when it comes to affirming that Scripture is “God-breathed,” everything hangs on where one starts. A dominant strand of the Evangelical tradition started with the assumption that, if God is perfect, and if Scripture is “God-breathed,” then Scripture must also be perfect or “inerrant.” Other “progressive” evangelicals have responded by observing that, as a matter of empirical fact, the Bible contains numerous discrepancies, historical inaccuracies, scientific errors and a host of other very-human imperfections. They have thus argued for a “limited inerrancy” position, contending that Scripture is “inerrant” only on matters of faith and practice or only on matters that it intends to teach.

Others offer alternative views, but it’s beyond the primary point of this post to assess the relative merits and difficulties of each of these views. The only relevant question for our purposes is: What warrants the starting point of each of these views?

For example, regarding the traditional evangelical argument for the inerrancy of Scripture what warrants the assumption that God’s “breathing” of Scripture must transfer his perfection? Since we have no a priori knowledge of what it means for God to “breath” something or of what a “God-breathed” book should look like, we are hardly in a position to insist that this process must result in a collection of writings that share God’s perfection.

The “limited inerrancy” camp that argues we must start with the Bible as it actually is and who thus conclude that it is only inerrant on matters of “faith and practice” are to be commended for at least starting with the Word God has in fact given us rather than one some assumed he should have given us. As a result, they have the distinct advantage over the inerrantists of not needing to engage in exegetical gymnastics to get around a veritable “encyclopedia” of “difficulties” in Scripture. The “limited inerrancy” group faces other problems, however. Not only is it not always easy to distinguish faith and practice from other “less spiritual” matters in Scripture, as critics have frequently noted, but more importantly, since we have no a priori knowledge of what a “God-breathed” book should look like, how do we know that God’s perfection is transferred when he “breathes” through human authors on matters of faith and practice?

Something similar could be asked of the other assessments of biblical inspiration and/or revelation. What warrants starting our reflections on God’s Word with a particular conception of God’s revelatory actions in history, or a particular anthropological or philosophical assessment of the human situation, etc.? This is not to say that insights cannot be gleaned from these various perspectives. But regardless of what insights they afford, this does not give them any distinct authority to provide a definitive assessment of what it means to confess Scripture as a “God-breathed” written revelation.

It’s my conviction that the only place to begin our reflections on the “God-breathed” nature of Scripture that can claim a trans-human authority is Jesus Christ. As with everything else pertaining to God, I submit that to understand the nature of biblical inspiration we must adopt Paul’s humble mindset and start with the confession that we “know nothing … except Jesus Christ and him crucified ” (1 Cor 2:2). From beginning to end our thinking about the nature of Scripture should be centered on the crucified Christ. Jesus is not one of God’s words; Jesus, as the God-become-human, is the Word to which all the words of Scripture bear witness. As such, we should regard him to be the essential content and controlling center of all “God-breathed” words.

In this light, we might analogically express the relationship between the diverse words of Scripture and God’s one and only Incarnate Word by comparing it to the way syllables and letters relate to words we utter or write. That is, just as syllables and letters find their sole function in forming the words we utter or write, so the diverse words of Scripture find their sole function in uttering the name “Jesus.”

Jesus is thus the truth of all truths, the Word that is spoken in all true words, and the revelation in all that is revelatory in Scripture. Despite it’s remarkable diversity, when read through the lens of Christ, “the whole of scripture is one book,” as Hugh of St. Victor expressed it, “the whole of scripture is one book, and that one book is Christ.”

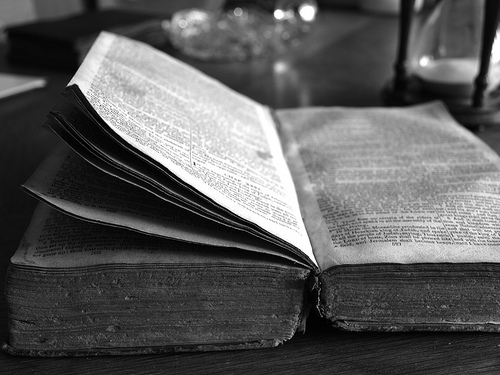

Image by __o__ via Flickr.

Category: General

Tags: Bible, Bible Interpretation, Cruciform Theology, Inerrancy

Topics: Biblical Interpretation

Related Reading

Who Rules Governments? God or Satan? Part 2

In the previous post, I raised the question of how we reconcile the fact that the Bible depicts both God and Satan as the ruler of nations, and I discussed some classical ways this has been understood. In this post I want to offer a cross-centered approach to this classical conundrum that provides us with…

“You” Means “Y’all”

Mrs Logic via Compfight Justin Hiebert over at Empowering Missional wrote a piece last week titled The Bible isn’t for you. Justin rightly points out that our individualistic mindset has caused us to misread huge portions of the Bible. He challenges us to read the Bible as a community rather than as individuals. It seems…

The Cruciform Center Part 4: How Revelation Reveals a Cruciform God

I’ve been arguing that, while everything Jesus did and taught revealed God, the character of the God he reveals is most perfectly expressed by his loving sacrifice on the cross. Our theology and our reading of Scripture should therefore not merely be “Christocentric”: it should be “crucicentric.” My claim, which I will attempt to demonstrate…

Podcast: Crucifixion of the Warrior God—The MennoNerds Interview

Paul Walker begins his interview with Greg about Crucifixion of the Warrior God. Paul Walker can be found at MennoNerds. Follow MennoNerds on Twitter. PART ONE: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0131.mp3 PART TWO: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0132.mp3 PART THREE: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0133.mp3 PART FOUR: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0134.mp3 PART FIVE: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0135.mp3 PART SIX: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0136.mp3 PART SEVEN: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0137.mp3 PART EIGHT: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0138.mp3 PART NINE: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0139.mp3 PART TEN: http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0140.mp3 PART…

The Heavenly Missionary

In his second sermon introducing the ideas in Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Greg suggests a metaphor to help us frame the things we encounter in the Old Testament that seem at odds with the God we find in the life and death of Jesus. God is a heavenly missionary who stoops to accommodate our…

Podcast: Must We Believe in the Historicity of the OT Stories to Trust in the Bible and in Jesus?

Things get deep, literarily, as Greg discusses deep literalism. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0384.mp3