We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Modern Theologians and the Centrality of Christ

During the twentieth century the development of a Christocentric reading of the Scriptures—which is crucial to understanding what I argue in Crucifixion of the Warrior God—surged in the wake of Karl Barth’s publication of his Romans commentary in 1916. It was justifiably described as a “bombshell” that fell “on the playground of the theologians,” demolishing the anthropocentric and rationalistic approaches of 19th century liberal theology and replacing it with a relentless and all-encompassing Christocentric focus.

Thereafter, an ever-increasing number of theologians from a variety of traditions have espoused theologies that could be broadly classified as “Christocentric.” And the last several decades have witnessed a virtual explosion of works in hermeneutics, homiletics, and systematic theology that have been categorized as Christocentric. To illustrate this Christocentric orientation among recent theologians and biblical interpreters, it seems appropriate to begin with my former professor at Yale, Brevard Childs. This pioneer in the field of biblical theology held that Christ is “the subject matter, substance, or res” of all Scripture. For this reason, he argued, the “fundamental goal” of biblical theology must be “to understand the various voices within the whole Christian Bible, New and Old Testament alike, as a witness to the one Lord Jesus Christ…”[1]

Arguing along similar lines, Leonhard Goppelt eloquently portrays Jesus as the “the focal point” of Scripture “that gathers all the rays of light that issue from Scripture.”[2] Peter Leithart holds that “Scripture is about Christ,” adding that “[t]he Christ who is the subject matter of Scripture is the totus Christus,” while Scott Swain has recently pointed out that even with all of its remarkable diversity, “God speaks the same Word” throughout Scripture, and that word is “Christ.”[3] All the literary forms of Scripture, he contends, “constitute a harmonious witness to the glory of the Word made flesh.”[4] Vern Poythress poignantly reflects the same orientation when he contends that “[t]he alternative to a Christocentric understanding of the Old Testament is not understanding it rightly…”[5]

In the same vein, Treier sums the conviction of most who comprise the Theological Interpretation of Scripture (TIS) movement—which I employ in Crucifixion of the Warrior God—over the last two decades when he states that, “whether one is reading the Gospels or … the Old Testament … all Scripture requires interpretation with the reality of Jesus Christ as the center of its narrative world.”[6] Similarly, Miroslav Volf writes: “For Christians, Jesus Christ is the content of the Bible, and just for that reason the Bible is the site of God’s self-revelation.”[7]

Nor is this revival of Christocentric hermeneutics a strictly Protestant phenomenon. There could be no better representative of a Christocentric approach to Scripture than Pope Benedict when he boldly states that “Christ is the key to all things …. [O]nly … by reinterpreting all things in his light, with him, crucified and risen, do we enter into the riches and beauty of sacred Scripture.”[8]

Yet, so far as I can see, no contemporary scholars go further in reflecting an intense and consist consistent Christocentric orientation than Thomas Torrance and Graeme Goldsworthy. Torrance exemplified an approach to Scripture that was “deeply and carefully Christological” and that emphatically displayed the conviction that “the heart of Scripture is Jesus Christ.”[9] Christ was for Torrance “the living text we read in the Bible.”[10] The most fundamental challenge for all theological interpreters of Scripture, therefore, is to “interpret it in terms of its scopus or goal, Jesus Christ, thus seeing it in its relation of depth with its truth in his incarnate person.”[11]

Similarly, Goldsworthy has consistently maintained that the most fundamental presupposition for Christian interpreters of Scripture must be that “… all texts in the whole Bible bear a discernible relationship to Christ and are primarily intended as a testimony to Christ.”[12] Goldsworthy has argued that if Jesus is “the one mediator between God and man,” then he must function as “the hermeneutic principle for every word from God.”[13] Hence, Goldsworthy has concluded, “the prime question to put to every text is about how it testifies to Jesus.” [14]

In fact, Goldsworthy and Torrance along with several others have argued that, as the mediator, redeemer, head and goal of all creation, Jesus must be regarded as the hermeneutical key not only to all Scripture but to all reality.[15]

[1] B. Childs, Biblical Theology of the Old and New Testaments, 80, 85.

[2] L. Goppelt, Typos: The Typological Interpretation of the Old Testament in the New, 58;

[3] P. J. Leithart, Deep Exegesis: The Mystery of Reading Scripture, 173; S. Swain, Trinity, Revelation and Reading, 25.

[4] Swain, ibid., 60.

[5] Poythress, God-Centered, 60.

[6] Treier, Introducing Theological Interpretation of Scripture, 67.

[7] M. Volf, “Reading the Bible Theologically,” in Captive to the Word of God: Engaging the Scriptures for Contemporary Theological Reflection, 6.

[8] Quoted in S. W. Hahn, Covenant and Communion: The Biblical Theology of Pope Benedict XVI, 82.

[9] T. Torrance, Atonement: The Person and Work of Christ, lix.

[10] Op. cit. xxx.

[11] Torrance, Atonement, xxxiii

[12] Goldsworthy, Preaching the Whole Bible, 113

[13] Goldsworthy, Gospel-Centered Hermeneutics, 21. See Torrance, Atonement xxx.

[14] Goldsworthy, Gospel-Centered Hermeneutics, 21.

[15] Goldsworthy, ibid., 251.

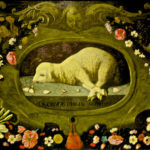

Photo credit: CharlesFred via VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Category: General

Tags: Bible Interpretation, Christocentrism, Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Cruciform Theology, Theology

Topics: Biblical Interpretation

Related Reading

Early Anabaptists and the Centrality of Christ

In a previous post, I wrote about the Christocentric interpretation of the Scriptures espoused by the magisterial Reformers, specifically Luther and Calvin. Their hermeneutic was focused on the work and the offices of Christ, but in my opinion the Anabaptists surpasses their approach because it focused on the person of Christ with an unparalleled emphasis…

Did God Give Violent Laws? A Response to Paul Copan (#13)

In his critique of Crucifixion of the Warrior God (CWG) at the Evangelical Theological Society annual meeting in November, Paul Copan takes issue with my contention that the violent dimension of OT laws reflects God accommodating the fallen and culturally conditioned perspectives of his people at this time. In my view, God was stooping to…

Christus Victor Atonement and Girard’s Scapegoat Theory

Many of the major criticisms of Crucifixion of the Warrior God that have been raised since it was published four weeks ago have come from folks who advocate Rene Girard’s understanding of the atonement. A major place where these matters are being discussed is here, and you are free to join. Now, I have to…

Podcast: Does a Jesus-Centric Theology Reduce God?

Greg challenges the traditional starting point of many theologies and defends starting our theology about God’s nature and character with what has been revealed about Jesus. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0325.mp3

The Problem with Christocentrism

As we’ve discussed in the previous posts, there has been a growing move toward a Christocentric orientation in theology since Barth, and especially over the last fifty years. I enthusiastically applaud this trend, for I’m persuaded it reflects the orientation of the NT itself, so far as it goes. The trouble is, it seems to…

What the Cross Tells Us About God

Whether we’re talking about our relationship with God or with other people, the quality of the relationship can never go beyond the level of trust the relating parties have in each other’s character. We cannot be rightly related to God, therefore, except insofar as we embrace a trustworthy picture of him. To the extent that…