We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

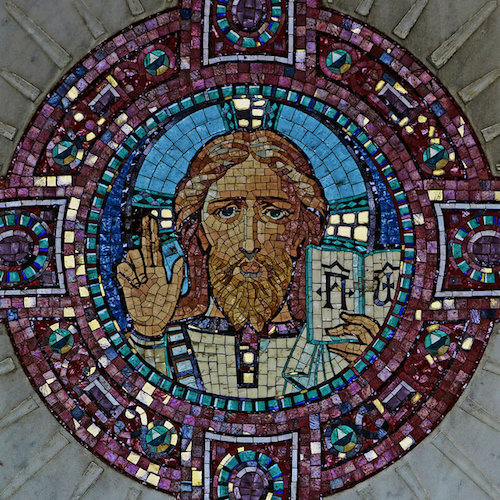

Jesus, the Word of God

“[T]he standing message of the Fathers to the Church Universal,” writes Georges Florovsky, was that “Christ Jesus is the Alpha and Omega of the Scriptures both the climax and the knot of the Bible.”[1] It was also unquestionably one of the most foundational theological assumptions of Luther and Calvin as well as other Reformers. Hence, for example, Luther argued that, “the function of all interpretation is to find Christ.”[2] In contrast to the so-called “objective” historical-critical approach, certain advocates of the Theological Interpretation of Scripture movement are exploring what it means to affirm that “… all texts in the whole Bible bear a discernible relationship to Christ and are primarily intended as a testimony to Christ,” as Graeme Goldsworthy put it.[3] Hence, “The prime question to put to every text is about how it testifies to Jesus?”[4]

We might say that Jesus is “the Word” of the words. T.F. Torrance succinctly captures the Christocentric focus both of a proper understanding of inspiration and of hermeneutics when he writes:

Since the Scriptures are the result of the inspiration of the Holy Spirit by the will of the Father through Jesus Christ, and since the Word of God who speaks through all the Scriptures became incarnate in Jesus Christ, it is Jesus Christ himself who must constitute the controlling centre in all right interpretation of the Scriptures.[5]

We might view the relationship between the diverse words of Scripture and God’s one and only Incarnate Word by comparing it to the way syllables and letters relate to words we utter or write. Just as syllables and letters find their function in forming the words we utter or write, so the diverse words of Scripture find their sole function in uttering the name “Jesus.” Vern Poythress comes close to this perspective when he states: “The Bible contains many distinct truths in the distinct assertions of its distinct verses.” Yet, in light of the fact that Jesus presented himself as the truth, Poythress adds, “all these cohere in the One who is truth.”[6]

Scott Swain reflects this view when he notes that, while God speaks in a wide diversity of ways throughout the progress of revelation, “ultimately God speaks the same Word … the word Christ.”[7] He continues, “God communicates his Incarnate Word (Jesus Christ) through his inscribed Word (Holy Scripture) for the sake of covenantal communication and communion.”[8]

In this light, we might say that Jesus is thus the truth of all truths, the Word that is spoken in all true words, and the revelation in all that is revelatory in Scripture. Despite its remarkable diversity, when read through the lens of Christ, as Hugh of St. Victor expressed it, “the whole of scripture is one book, and that one book is Christ.”

[1] G. Florovsky, Aspects of Church History, Vol.IV (Belmont, Mass: Nordland Pub. Co., 1975), 38

[2] Dockery, “Christological Hermeneutics,” 191. F.W. Farrar, History of Interpretation (London: Macmillan, 1886), 232.

[3] Goldsworthy, Gospel-Centered Hermeneutics, 252; cf. idem, Preaching the Whole Bible, 21. For an excellent defense of a Christocentric approach to Scripture that is oriented toward its practical significance, see Smith, Bible Made Impossible, 93-126.

[4] Goldsworthy, Gospel-Centered Hermeneutics, 252; cf. idem, Preaching the Whole Bible, 21.

[5] T. F. Torrance, The Trinitarian Faith: The Evangelical Theology of the Ancient Catholic Faith (Edinburgh: Clark, 1988), 39.

[6] V. Poythress, God-Centered Biblical Interpretation (Pillipsburg, NJ, 1999), 58.

[7] S. Swain, Trinity, Revelation and Reading: A Theological Introduction to the Bible and Its Interpretation (New York: T & T Clark, 2011), 25. See ibid., 37.

[8] Swain, ibid., 60.

Photo credit: Leo Reynolds via Visualhunt / CC BY-NC-SA

Category: General

Tags: Bible Interpretation, Cruciform Theology, Jesus

Topics: Biblical Interpretation

Related Reading

When Jesus Questioned the Father

Though the sinless Son of God had perfect faith, we find him asking God the Father to alter the plan to redeem the world through his sacrifice—if it is “possible” (Matt. 26:42). As the nightmare of experiencing the sin and God-forsakenness of the world was encroaching upon him, Jesus was obviously, and understandably struggling. So,…

Did Yahweh Crush His Son?

Though Isaiah was probably referring to the nation of Israel as Yahweh’s “suffering servant” when these words were penned, the NT authors as well as other early church fathers interpreted this servant to be a prophetic reference to Christ. Speaking proleptically, Isaiah declares that this suffering servant was “punished” and “stricken by God” (Isa 53:4,…

How can you believe Matthew’s report about the Jewish cover up of the resurrection?

Question: In Matthew it’s reported that Jewish authorities tried to cover up the resurrection of Jesus by saying the disciples stole the body while the guards were sleeping. I don’t buy it. How would Matthew know about this story, since it was a secret conversation the authorities had with the guards? And how could they…

Are You Guilty of Marcionism?

Greg responds to the question of whether or not his cruciform hermeneutic is anything like the heresy of Marcion, who basically advocated throwing out the Old Testament. (Spoiler: it’s not.)

Something Else is Going On

The violent portraits of God in the Old Testament are a stumbling block for many. In this short clip, Greg introduces the idea that “something else is going on” in these passages, and that we can begin to see this something else when we put our complete trust in the character of God as fully revealed in…