We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Four Principles of the Cruciform Thesis

In the second volume of Crucifixion of the Warrior God, I introduce how four dimensions of the revelation of God on the cross (as introduced in this post) lead to four principles that show us how to unlock aspects of the OT’s violent divine portraits and thus disclose how a given portrait bears witness to the cross. Taken together, these four principles comprise the Cruciform Thesis. This post provides a brief introduction to these four principles.

The Principle of Cruciform Accommodation

This principle holds that the cross, rather than a presupposed philosophical conception of what a “perfect being” should be like, must serve as the primary criterion by which we access the degree to which any biblical portrait of God is and is not a divine accommodation. Any divine portrait that reflects the character of God revealed on the cross is a direct revelation of God’s true character and will. Any that fall beneath what is revealed on the cross must be considered an accommodation of a stooping God.

The biblical narrative reflects God’s willingness to bend his ideals to accommodate the fallen and culturally conditioned state of his people. God is consistently depicted as a heavenly missionary who must temporarily appear to condone grotesque practices and beliefs that he actually deplores if he intends to gradually influence his people away from these practices and beliefs. This is illustrated by the shared assumption of the OT authors with their ANE neighbors that they were exalting a national warrior deity by giving credit to their god for the ruthless bloodletting. In this light, the OT’s depictions of Yahweh as a violent warrior testify to God’s covenantal faithfulness. These portraits demonstrate just how low God was willing to stoop remain in covenant with, and to continue to work through, his fallen and culturally conditioned people.

The Principle of Redemptive Withdrawal

The second principle is that the cross reveals the way that Jesus suffered the “wrath” that we deserved. To bring about judgment of sin, the Father did not need to become angry with Jesus or to act violently toward Jesus. Nor did he need to cause anyone else to act violently toward Jesus. Instead, the Father merely withdrew his protective presence, thereby delivering Jesus over to wicked people and fallen powers that were already “bent on destruction” (Isa 51:13). God wisely used the self-acquired evil character of Satan and other fallen powers against them, causing the kingdom of darkness to self-implode.

We see this principle at work as biblical authors reflect the understanding that punishment is related to sin in the same way that effects are related to causes. The punishment for sin is intrinsic to the sin that is being punished, which is precisely why God need not act violently when he allowed intractable sinners to fall under judgment. When God sees that his merciful protection of people from the destructive consequences of their choices is only serving to further harden these people in their sin, God has no choice but to withdraw his protection and allow their sin to ricochet back on them as a divine judgment.

Judgment is not God’s last word, however. When the Father allowed his Son to suffer the death-consequences of our sin, it was with a view toward his resurrection and the ultimate restoration of humanity and the whole creation. Whenever God sees he must withdraw his protective presence to allow people to suffer the destructive consequences of their choices, he does so with a grieving heart and with redemptive rather than vengeful motives.

The Principle of Cosmic Conflict

The NT understands Jesus’s crucifixion to be God’s decisive battle against, and victory over, the powers of darkness. We must, therefore, read Scriptures with the awareness that humans are not the only violent agents at work when God sees he must withdraw his protection to allow rebels to come under judgment.

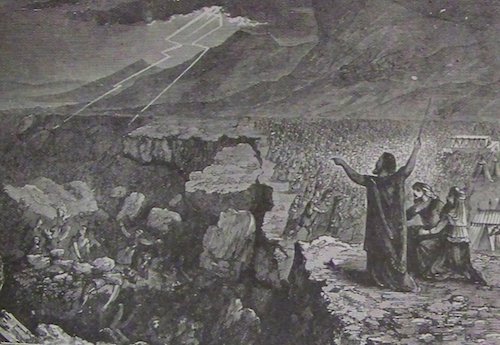

There is extensive confirmation of this throughout the Scriptures. To cite one example, Paul mentions that “grumblers” in the OT were destroyed by “the destroying angel” (1 Cor 10:10) despite the fact that there was no “destroying angel” mentioned in the narrative describing the judgment of Korah’s grumbling rebellion (Num 16). However, when we read Numbers 16 within the ANE worldview, we find indications in the narrative itself that the judging agents—the swallowing earth, the fire, and the plague—would have been understood by the original audience to be malevolent cosmic forces of destruction. Paul’s introduction of the “destroying angel” finds support in the narrative itself, which confirms our cross-based assumption that destructive cosmic agents are always at work.

The Principle of Semiautonmous Power

The revelation of God on the cross depended upon Jesus obeying the will of the Father. Therefore, we must take seriously the fact that Jesus could have used the divine authority that had been trusted to him to call down legions of angels to his defense (Matt 26:52), which would have been contrary to the will of the Father. Based on this, whenever God grants a degree of divine power to human agents, they possess some degree of “say-so” over how this authority is used. This is why God cannot be held responsible when servants he endows with extraordinary divine power end up using this power in destructive ways.

This is illustrated in a variety of places in the Scripture. For example, based on this principle, we cannot assume that the curse of Elisha that resulted in 42 young men being mauled by bears was in accordance with God’s will (2 Kings 2:23-24). Nor should we assume that the supernatural fire that Elijah used to incinerate 100 innocent messengers reflects God’s will (2 Kings 1:10-12). The fact that Jesus rebuked his disciples for wanting to repeat this destructive miracle was enough to prove that it did not reflect God’s will (Luke 9:51-57). When God endows people with degree of supernatural power, they possess some degree of influence over how this power is used.

________

These four principles disclose how the slain lamb unlocks the secret cross-centered meaning of violent divine portraits of God within the Bible. But this “secret” can only be discerned by faith, which is why the slain lamb only discloses it if we remain confident that he is in fact the all-surpassing revelation of God’s eternal character. Out of fidelity to Christ crucified and to our call to be peacemakers, and for the sake of a world that continues to perpetuate the same mindless cycle of violence that has imprisoned it since the Fall, it is imperative that Jesus-followers today renounce this warrior god once and for all and regard it to be the “nothing” that the cross made it to be.

—Adapted from Crucifixion of the Warrior God, pages 1252-1261

Image: Destruction of Korah Dathan and Abiram (illustration from the 1890 Holman Bible)

Category: General

Tags: Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Cruciform Theology

Topics: Interpreting Violent Pictures and Troubling Behaviors

Related Reading

Why Are Jesus’s Parables So Violent? (podcast)

Greg pops the hood to offer a helpful tutorial on how parables operate. Episode 609 http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0609.mp3

Jesus Refuted Old Testament Laws

Although it’s clear that Jesus regarded the Old Testament as the inspired word of God, he also directly challenged aspects of the Old Testament law. To illustrate, Jesus was repudiating Sabbath law when he defended his disciples’ harvesting of food on the Sabbath (Mt 12:1-14; cf. Ex. 34:21). Some scholars argue that the disciples were…

Podcast: The Making of the Cross Vision Study Guide

Deacon discusses the Cross Vision Study Guide. Book is available HERE: Cross Vision Study Guide http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0409.mp3

Divine Accommodation in the Early Church

One of the basic points made in The Crucifixion of the Warrior God is that the Old Testament reveals how God adjusts his revelation and instructions to accommodate the weakness of his covenant people. This is actually not a new observation as is reflected in a variety of ways throughout Church history. For example, in…

Is the Bible History?

Even though I argued for interpreting the final form of the biblical canon as opposed to using the history behind the text in my post yesterday, I am not endorsing the radical post-modern view that biblical texts possess “semantic autonomy” and thus lack any historical referentiality. While I have no problem whatsoever accepting that God used folklore and myth…

Podcast: Does the Cruciform Hermeneutic Sabotage Open Theism?

Greg plays Peek-a-Boo with God and considers whether those verses Open Theists use to support Open Theism might simply be times when God is accommodating for us. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0236.mp3