We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

The Phinehas vs. Jesus Conundrum

I’ll be frank. This is not a blog that will be easy for some people to read. But it’s a blog I believe every follower of Jesus should read – even if you have to force yourself to press on. It’s about something we all wish was not true. It’s about the way the Bible has throughout history been used to justify and motivate violence – in Jesus name. I’ve also included some of my research in the footnotes, because I’ll be discussing material that is typically edited out of public education curriculum, and even more so by Christian curriculums. Hence it’s material that most know little about, so I encourage readers to dig deeper.

If you’re a follower of Jesus, please read on.

In Numbers 25 the Lord tells Moses to gather together and execute in broad daylight all the ringleaders of a group of guys who had defiled themselves by having sex with Moabite women and worshipping their idols (vs. 1-4). While the whole congregation of Israel was assembled before Moses, a man and his recently wed Moabite wife came before them weeping, apparently out of fear, hoping for mercy (v 6). Suddenly a guy named Phinehas went out, grabbed a spear, and bludgeoned both of them, apparently with one thrust (vs 8). The Lord praised the “zeal” of Phineas and thus lifted a plague that had already killed 24,000 (vs.8- 11, cf. Ps 106:29-31).

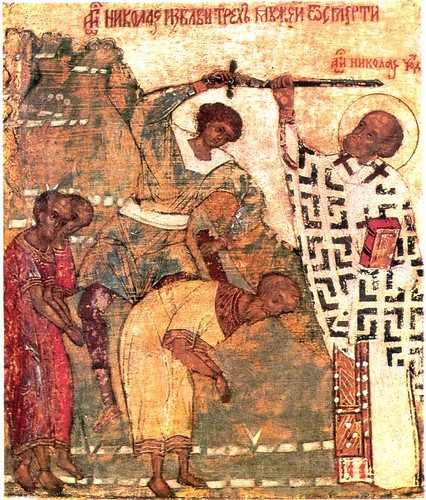

A follower of Jesus can’t help but notice the radical contrast between the portrait of God commending Phinehas for his use of the sword, on the one hand, and Jesus’ rebuke of Peter for using the sword, on the other (Mt 26:51-52). Unfortunately, it’s an undeniable truth that throughout history the example of Phinehas has exercised more influence on Christian attitudes toward violence than Jesus’. As J.J. Collin’s has demonstrated, the “zeal of Phinehas” has served as a paradigmatic slogan for religiously motivated violence in the Judeo-Christian tradition throughout history.[1]

My research for The Crucifixion of the Warrior God uncovered a wealth of scholarly research demonstrating the manner in which violent stories in the Bible and in other literature that is considered sacred has justified and motivated religious violence in all the world’s religions. The brutally violent history of the Christian Church from the fifth century on, massacring heretics, Muslims, witches, and even other Christians, all carried out with presumed biblical authority and in the name of God, bears witness to this sad truth.[2] Referring to the story of Yahweh telling the Israelites to “show no mercy” as they slaughter “everything that breathes” in Canaan (Deut. 7:2; 20:16), Kenton Sparks notes that throughout history, “Jewish and Christian readers of the Bible have used these texts to justify wholesale, violent, exterminations of their enemies.”[3] Speaking specifically of the crusades in the medieval period, Joseph Lynch reminds us that these religious massacres are simply “not comprehensible without factoring in the Old Testament, which permeated not just the language but also the self-view and behavior of the warriors.”[4]

The imagery of Israel violently invading Canaan became a motiving paradigmatic symbol in an especially strong way when Europeans conquered America. To illustrate, Sparks sites the testimony of one American colonist who, after his group had completely annihilated an entire tribe of Native Americans, testified:

Sometimes Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents…We had sufficient light from the Word of God for our proceedings….It was a fearful sight to see them frying in the fire, with steams of blood quenching it; the smell was horrible, but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice.[5]

These European invaders of America had “the zeal of Phinehas” as many explicitly identified themselves with the Israelites and the indigenous population with the Canaanites. [6] The Puritan preacher Ezra Stiles went on to depict George Washington as America’s “Joshua” theorizing that the natives were literal descendants of the Canaanites.[7] Since it’s typically edited out of all but the most academic American history books, most people are unaware of the full depth of the depravity manifested in many Europeans’ treatment of the indigenous population — all carried out under the auspices of the authority of the Bible and the Church.[8] Given what Karlheinz Deschner has called the “criminal history” of our Church, sanctioned by what some have called the Bible’s “texts of terror,” you can understand why an increasing number of westerners find themselves resonating with the opinion of Mieke Bal when she writes: “The Bible, of all books, is the most dangerous one, the one that has been endowed with the power to kill.”[9]

As followers of Jesus, we must honesty face the challenge that the ugly, violent aspects of our Bible and our history pose for us. As followers of Jesus, we are called to not only refrain from violence, but to be peacemakers (Mt 5:9) and “ministers of reconciliation” and “ambassadors” of the kingdom (2 Cor. 5:19). Yet our Bible, which we confess to be “God-breathed” (2 Tim.3:16), contains material that is violence-making rather than peace-making. To this day it continues to incite violent attitudes, if not outright violent behavior.

Just two years ago a billboard in Texas said “Pray for Your President” just under a picture of Obama, citing Psl.109:8.[10] This verse calls for the Psalmist’s enemy to die soon – “let his days be few” and goes on to pray that “his children” would be “fatherless,” “his wife a widow,” and “his children…wandering beggars” who are “driven from their ruined homes” (vs.9-10). This is a Phinehas prayer, not a Jesus prayer. Jesus rather taught us to pray for our enemies, to bless our enemies, and to follow his example of praying for the forgiveness of our persecutors (Mt 5:44; Lk. 23:34)

In light of all this, we must ask ourselves: What does it mean to be makers of peace and bringers of reconciliation when the Bible we confess to be “God-breathed” has material that continues to inspire violent attitudes, if not outright violence? Since Jesus and the earliest disciples confessed the whole Old Testament to be the inspired Word of God, I do not for a moment think that denying the Bible’s violent material is an option. Confessing Christ to be Lord entails that we cannot usurp his own teaching by cutting out material we don’t like. I don’t see how one can confess Christ to be Lord and yet correct his theology, especially about a matter as foundational as this.

At the same time, confessing Christ as Lord, and honoring his call to be peacemakers, means that we can no longer remain silent about the truth that this material contradicts the enemy-loving, non-violent attitude he commands us to have. As a number of concerned scholars have been saying, to remain silent about violence-inciting material is to condone it and to thus bear some responsibility for the violence it incites. Indeed, even Jesus renounced the Old Testament’s “eye for an eye” commands (Lev. 24:19-20; Ex. 21:24) and replaced them with his command to “turn the other cheek” and to love our enemies ( Mt 5:38-45).

The question I therefore leave you with is this: Is there a way to affirm that all Scripture, including its violent stories, violent prayers, and violent depictions of God, are “God-breathed,” while at the same time renouncing its violence? For in confessing Christ as Lord, it seems we are bound to do both. It may seem like an impossible conundrum, but I have found that impossible conundrums are sometimes an opportunity for the most profound insights.

Think about it.

Thank you for pressing through.

And until a resolution is forthcoming, I implore you to please follow the example of Jesus, not Phinehas.

Jim Forest via Compfight

Category: Essays

Tags: Cruciform Theology, Essay, Jesus, OT Violence, Phinehas, Violence

Topics: Interpreting Violent Pictures and Troubling Behaviors

Related Reading

Crucifying Transcendence

The classical view of God’s transcendence in theology is in large borrowed from a major strand within Hellenistic philosophy. In sharp contrast to ancient Israelites, whose conception of God was entirely based on their experience of God acting dynamically and in self-revelatory ways in history, the concept of God at work in ancient Greek philosophy…

Podcast: Doesn’t Claiming that the Old Testament Writers were Sometimes Wrong Inevitably Lead to a Slippery Slope?

Greg talks about cataphatic prayer and the role of the imagination. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0470.mp3

Q&A: Condemning Sin

Q: I have a question about how you answer the rare occasions when Jesus apparently felt it necessary to publicly condemn sin: like the cleansing of the temple and his very strong judgments on Pharisees and rulers in Matthew 23. Also John the Baptist who not only preached strongly regarding public sins but was imprisoned…

Why Did Jesus Curse the Fig Tree?

One of the strangest episodes recorded in the Gospels is Jesus cursing a fig tree because he was hungry and it didn’t have any figs (Mk 11:12-14; Mt 21:18-19). It’s the only destructive miracle found in the New Testament. What’s particularly puzzling is that Mark tells us the reason the fig tree had no figs…

Response to the September 11th attacks

Was God Punishing Us? Since the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11th, many people have asked the question, “Why did God allow this to happen?” In response, some Christian leaders have suggested that God was punishing our country for reaching an all-time low in moral behavior. As one well-known…

A Brief Theology of the Trinity

“The economic Trinity is the immanent Trinity, and the immanent Trinity is the economic Trinity.” This is the maxim introduced by the Catholic theologian Karl Rahner that should shape our discussion of the Trinity. It is simply a short-hand way of saying that since the way God is toward us in Christ truly reveals God,…