We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

How is the Bible “God-Breathed”?

The historic-orthodox church has always confessed that all canonical writings are “God-breathed” (1 Tim 3:16). But what exactly does this mean? How could God guarantee that the writings that his “breathing” produces are precisely what he intended without thereby undermining the autonomy of the agents he “breathes” through? In other words, did God breathe the Scriptures by unilaterally causing the authors to write what they wrote?

If God “breathed” all Scripture in the process of “breathing” Jesus, and if everything Jesus was about is thematically anchored in the cross, as I’ve argued in yesterday’s post, then I submit our understanding of the nature of “God-breathed” Scripture also be anchored in the cross. The question we must consider, therefore, is how God’s “breathing” on Calvary might inform our understanding of his “breathing” in Scripture?

The most important aspect of God’s communicative action on Calvary, I believe, is this: On Calvary, God revealed himself not just by acting toward humans, but by allowing himself to be acted on by humans as well as the fallen Powers. God certainly took the initiative in devising the plan of salvation that included the Son of God becoming human at “the right time” for him to get crucified. And God was certainly taking the initiative as Jesus taught and acted in provocative ways that were certain to get him crucified. Hence, Scripture says that part of God’s “deliberate plan and foreknowledge” was to have Jesus handed over (Ac 2:23) to wicked people to do what God’s “power and will had decided beforehand” (Ac 4:28).

At the same time, as active as God was in “breathing” his communicative action on Calvary, we must also notice that this revelatory act took place by God allowing wicked humans and forces of evil to act out their wicked and violent intentions against Jesus. Indeed, the physical and verbal assaults Jesus absorbed in the process of being crucified were actually just a microcosm of the sin of the world that Jesus absorbed on the cross, thereby allowing every human throughout history to act on him. It is within this dialectic of acting and being acted upon that God communicates his true identity, and given that his true identity is humble, self-sacrificial love, it’s hard to see how it could have been otherwise. A deity whose essence was power could reveal himself by unilaterally acting upon others, but not the one true triune God whose eternal existence is an unending act of three divine Persons giving themselves wholly over to one another.

The cross is thus the full revelation of God’s character precisely because it wasn’t a unilateral action of God toward humans but rather came about, in part, by God humbly allowing human and angelic agents to engage in hostile activity against God. For this same reason, this paradigmatic communicative act was not merely a revelation of God’s power but also of God’s wisdom, as God wisely turned the evil he absorbed for good, including the good of glorifying his Father by revealing his true self-sacrificial character as well as the good of defeating the powers of evil and the good of freeing humans from their oppression to sin and the devil.

Now, given that the paradigmatic act of self-revealing “breathing” on Calvary is the ultimate telos of all divine “breathing,” and given that this act involved agents being allowed to act on God as well as God acting on agents, how can we not assume that this holds true for all of God’s acts of self-revealing “breathing”? If we accept this, it fundamentally transforms our understanding of the “God-breathed” nature of Scripture. Among other things, it means that our confession that Scripture is divinely inspired should not be understood as suggesting that all that is written within the canon is the result of God unilaterally acting through human authors. Reflecting God’s cruciform character, these writings also reflect God humbly permitting the culturally-conditioned and sin-tainted worldviews of biblical authors to act upon him.

Moreover, as is true of God’s revelation on Calvary, this means that Scripture’s inspiration must be understood not only as a reflection of God’s power but also as a reflection of God’s wisdom. As with the cross, we must expect to see God wisely achieving his good communicative ends by utilizing the various ways he has allowed the limited and fallen worldviews of Scripture’s human authors to act upon him and to thereby condition the form his communication in Scripture takes.

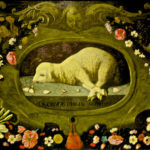

Image by Snutschi via Flickr.

Category: General

Tags: Bible, Bible Interpretation, Cross, Cruciform Theology, Inspiration, Jesus

Topics: Biblical Interpretation

Related Reading

Podcast: Where Does Forgiveness Fit in a Cruciform Theology?

Greg offers looks at forgiveness in a realm of natural consequences. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0298.mp3

Was Jesus Really Human Like the Rest of Us?

Did Jesus really live as a human like you and I do? Or did he walk around with special divine powers that we don’t have? In the previous post, I introduced the question: How was God both fully God and fully man? I explained the classical model of the Incarnation which views the incarnate Jesus…

The Incarnation: Paradox or Contradiction?

We’re in the process of flushing out the theology of the ReKnew Manifesto, and we’ve come to the point where we should address the Incarnation. This is the classical Christian doctrine that Jesus was fully God and fully human. Today I’ll simply argue for the logical coherence of this doctrine, viz. it does not involve…

Christus Victor Atonement and Girard’s Scapegoat Theory

Many of the major criticisms of Crucifixion of the Warrior God that have been raised since it was published four weeks ago have come from folks who advocate Rene Girard’s understanding of the atonement. A major place where these matters are being discussed is here, and you are free to join. Now, I have to…

Did the Father Suffer on the Cross?

When I argue that the cross is a Trinitarian event (See post), some may suspect that I am espousing Patripassionism, which was a second and third century teaching that held that God the Father suffered on the cross. While this view was often expressed as a form of heretical Modalism, and while the Patristic fathers…

The Cruciform Way of the Lamb

In this video, Greg offers insight into how to read the Bible with the cross at the center of the revelation of God, thereby reframing how we interpret the violent and nationalistic passages of the Old Testament. Travis Reed from The Work of the People did a series of interviews with Greg a while ago and…