We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Jesus, the New Israel

The Gospels present Jesus and the Kingdom he inaugurated as the fulfillment of Israel’s story. For example, Jesus’ birth fulfills Israel’s longing for a Messiah; his return from Egypt as a child mirrors their Exodus out of Egypt; his temptations in the desert allude to Israel’s temptations in the desert; his twelve disciples recall the 12 tribes of Israel; Jesus’ five sets of teachings in Matthew are a parallel of Moses’ Pentateuch; his sufferings fulfill the call of Israel to be a suffering servant, and his resurrection completes the hoped for resurrection of Israel. In sum, the Gospel authors see Jesus as “the appropriate ending” of the story of Israel, as NT Wright notes. Remembering that “Son of God” was a title for Israel as well as of the Messiah, the life, death and resurrection of God’s Son in the Gospels must be understood as “the climax of [Israel’s] election as well as the fullest self-revelation-in-action of the sovereign God.”[1]

All the Gospel authors, but especially Matthew, see various details of Jesus’ life as fulfilling certain details in the OT narrative. While there are a few passages in which it is clear these authors believed Jesus fulfilled something that was predicted in the OT, the vast majority of examples cannot possibly be understood along these lines. They rather reflect the thoroughly Christocentric perspective of these authors on the OT. Here I want to illustrate this point with two examples from Matthew.

Matthew’s Christocentric Interpretation of Rachel’s Weeping. The first example I want to highlight is found in Matthew 2:16-18. Here we read how Matthew interprets the wailing of mothers in Bethlehem after Herod’s massacre to be the fulfillment of parents wailing as they journeyed through Ramah as they were being deported to Babylon. This is a reference back to Jeremiah 31:15. It’s evident that Matthew was not suggesting that the Jeremiah passage predicted the Bethlehem massacre, for there is, in fact, nothing predictive about Jeremiah 31:15. Rather, reflecting an intensely Christocentric focus, Matthew understands the wailing that surrounded the birth of Jesus to be the quintessential expression of the sort of wailing Jewish mothers have often endured at the hands of Gentiles, as expressed in Jeremiah 31:15. If the application strikes us as a stretch, this simply reflects the fact that we don’t share Matthew’s interpretive strategy or the intensity of his Christocentric conviction that the real significance of every passage is the significance it has in the light of Christ.

Matthew’s Christocentric Fusion of Two Texts. The second example is found in Matthew 21:1-5, which narrates Jesus’ entrance into Jerusalem. Here Matthew sees this act as the fulfillment of two awkwardly spliced together verses from Zechariah and Isaiah (Zech. 9:9; Isa 62:11). Matthew is again not suggesting these passages predicted Jesus’ entrance, for there is in fact nothing predictive about either passage. Rather, in Jesus’ royal-yet-humble entrance into Jerusalem, Matthew sees the supreme expression of the sort of king Israel has always longed for, as reflected (in Matthew’s mind) in the two passages he splices together.

Perhaps even more significantly, we should note that the Zechariah portion of the Scripture Jesus “fulfills” in Matthew is taken from the Septuagint. While it’s apparent that the “donkey” and “colt” in the original Hebrew of Zechariah 9:9 is an example of Hebraic parallelism and thus refers to one animal, the translators of the Septuagint for some reason inserted a kia (“and”) between the donkey and colt, thereby rendering them as two different animals. Following this translation, Matthew rewrote Mark’s account (assuming Markan priority) to portray Jesus as somehow riding into Jerusalem on both animals (Mt 21:7). For the same reason Matthew modified Mark’s account of the disciples finding the donkey to include her colt (Mk 11:2-3//Mt 21:3).

From our vantage point, Matthew’s interpretive technique and the unusual depiction of Jesus that results from it can’t help but seem forced, perhaps to the extreme. For some readers, they may also raise questions about the meticulous historical accuracy of Matthew’s portrait and thus about the inspiration of his account. These questions need not detain us presently, however, for our only interest concerns the manner in which Matthew’s interpretation reflects the intensity of his Christocentric convictions.

This just illustrates how everything in Scripture—even, apparently, the insertion of a kia (“and”) in the Septuagint—is assumed to bear witness to Jesus and thus to find its fulfillment in Jesus. Jesus brings God’s dealings with Israel throughout the OT to a climatic fulfillment, and so any aspect of Jesus’ life that in any way has a parallel in the OT is seized by the Gospel writers as “fulfillment” of that parallel.

[1] N.T. Wright, “Christian Origin’s and the Question of God,” in Engaging the Doctrine of God: Contemporary Protestant Perspectives, ed. B. McCormack (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 21-36.

Photo credit: StateofIsrael via VisualHunt / CC BY-SA

Category: General

Tags: Israel, Jesus, Old Testament

Topics: Biblical Interpretation, Christology

Related Reading

The Perfect Love of God

The Father, Son and Spirit exist as the infinite intensity and unsurpassable perfection of eternal love. We know this about the triune God not by speculation but because Jesus demonstrated that love (Rom 5:8) in his willingness to go to the furthest extreme possible to save us. When the all-holy God stooped to become our…

Can You Believe It?

The origin of human sin and the world’s oppression goes back to a deceptive, untruthful picture of God given to Eve by Satan. Jesus came, in part, to finally reveal the absolute truth about God. He is the way and the truth (alethia) and the life (Jn 14:6). The word “truth,” literally means “uncovered.” And…

Was Jesus Really Human Like the Rest of Us?

Did Jesus really live as a human like you and I do? Or did he walk around with special divine powers that we don’t have? In the previous post, I introduced the question: How was God both fully God and fully man? I explained the classical model of the Incarnation which views the incarnate Jesus…

The “Christus Victor” View of the Atonement

God accomplished many things by having his Son become incarnate and die on Calvary. Through Christ God revealed the definitive truth about himself (Rom 5:8, cf. Jn 14:7-10); reconciled all things, including humans, to himself (2 Cor 5:18-19; Col 1:20-22), forgave us our sins (Ac 13:38; Eph 1:7); healed us from our sin-diseased nature (1…

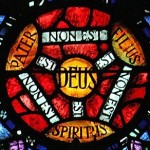

Does the Doctrine of the Trinity Matter?

Jesus reveals the greatest, most beautiful, and mysterious aspect of God when he, despite being himself God Incarnate, relates to God as his “Father” and refers to God as “the Holy Spirit.” There is, of course, only one God (1 Cor 8:6). Yet Jesus reveals that God somehow exists as Father, Son and Holy Spirit.…

Radical is in the Eye of the Beholder

Josias Hansen is a Brazilian-born, Charismatic Mennonite student at Luther Seminary in St. Paul, MN. Together with Third Way Church, Josias enjoys experimenting with what it looks like to take Jesus seriously as a jolly community of kingdom disciples. Was Jesus a radical? Did he do and teach radical things? What if I were to tell…