We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Challenging the Assumptions of Classical Theism

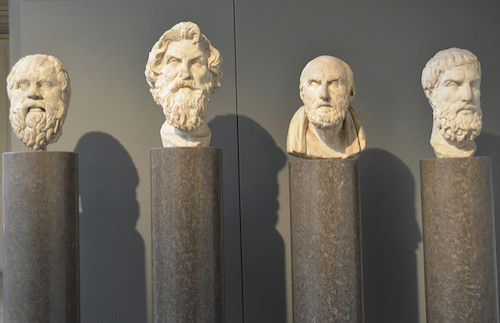

What came to be known as the classical view of God’s nature has shaped the common, traditional way that most people think about God. It is based in the logic borrowed, mostly unconsciously, from a major strand within Hellenistic philosophy. In sharp contrast to ancient Israelites, whose conception of God was entirely based on their experience of God acting dynamically and in self-revelatory ways in history, the concept of God at work in this strand of ancient Greek philosophy was most fundamentally a concept that explained all that was not self-explanatory—namely, the contingent, ever-changing, limited, compound world.

This ultimate explanation, these philosophers generally assumed, must constitute the antithesis of all that needs to be explained, for otherwise we would end up in an infinite regress. Hence, for all the significant differences among the Platonic, Stoic, and Peripatetic philosophers who comprise this strand, at the core of their program was a logic that moved away from contingency, change, and composite being and moved toward a reality that was altogether necessary, unchanging, and simple. They commonly called this ultimate explanation “the One.”

For this and other reasons, contingency, change, and composite being came to be viewed as inferior, and in the platonic school, less real, than that which is necessary, unchanging and simple. And the dominant way the philosophers in this strand worked toward their ultimate explanation was via negativa—a way of describing “the One” by what he is not. They attempted to form a conception of a reality that remains when all that is not self-explanatory is stripped away.

The first unambiguous example of this via negativa was Anaximander’s concept of aperion—the “indefinite.” Following this, the conception of the ultimate reality that explains all things developed and evolved in a number of ways within the different streams of the Hellenistic philosophical tradition. By the second and third centuries, it was widely assumed in Hellenistic philosophical circles that God (or “the One”) was altogether simple and “above” contingency, becoming, limitations, emotions, rational thought, and possibly time.

The literature debating the extent to which early Church Fathers were or were not influenced by this concept of God is massive. Here I will simply make one observation to illustrate my point. Contemporary defenders of the early Fathers tend to argue that the specific and particular theological concepts that have parallels in Hellenistic philosophy are significantly modified when appropriated by church fathers. In addition, they produce statements by these Fathers that reflect a rather hostile attitude toward pagan philosophy. I believe these defenses are, to a large degree, successful, but they fail to see the forest through the trees in terms of the kind of influence I’m asserting.

My contention is that the important line of influence isn’t at the level of any particular ideas. It concerns the most fundamental logic that is at work in this strand of Hellenistic philosophy. It concerns the fundamental difference between the Hellenistic conception of God that is arrived at by moving away from the contingent world and the Hebraic conception of God that is received as a revelation as God moves toward, interacts with, and eventually unites himself to the contingent world in the person of Jesus Christ. It’s my contention that, if people start and orient all their theological reflection around the One in whom God united himself to the world of contingent becoming, it would never occur to them to arrive at a conception of God’s nature that is the negation of contingency and becoming—viz., a conception of God as essentially atemporal, immutable, and impassible.

Let’s consider a few questions:

- If we resolve that all our reflections about God are to be anchored in the one in whom God became a man, would it ever occur to us to think that God’s essence is devoid of becoming?

- If our thinking about God never veers from the one who was tortured and crucified at the hands of wicked agents, would it ever occur to us to imagine that God’s essence can’t be affected by anything outside of God?

- If our thinking about God remains steadfastly focused on the one who suffered a hellish death on the cross, would it ever occur to us to think that God’s essence never suffers?

- If all our thinking is oriented around the crucified Christ, would we ever imagine that a God whose essence had no “before “ or “after” and whose essence had no potential to change, or to be affected, or to suffer was more glorious than a God who in his very essence experienced sequence and had the potential to change, be affected and suffer?

So far as I can see, the answer to all such questions is a definitive “no.” If all our reflections on God’s being are, from start to finish, focused on the crucified Christ, I believe we are rather empowered to discern God’s true nature not over-and-against the Crucifixion, but in the Crucifixion itself.

Photo credit: tnchanse via Visualhunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Category: General

Tags: Classical Theism, Cruciform Theology, Platonism

Topics: Attributes and Character

Related Reading

Do the Gospels Fabricate Prophetic Fulfillment?

Skeptically-inclined scholars, and especially critics of Christianity, frequently argue that the Gospel authors created mythological portraits of Jesus largely on the basis of OT material they claim Jesus “fulfilled.” In other words, they surveyed the OT and fabricated stories about how Jesus fulfilled those prophecies. In response, it’s hard to deny that there are certain…

Christ-Centered or Cross-Centered?

The Christocentric Movement Thanks largely to the work of Karl Barth, we have over the last half-century witnessed an increasing number of theologians advocating some form of a Christ-centered (or, to use a fancier theological term, a “Christocentric”) theology. Never has this Christocentric clamor a been louder than right now. There are a plethora of…

The Cross Above All Else

The way to know what a person or people group really believes is not to ask them but to watch them. Christians frequently say, “It’s all about Jesus,” but our actions betray us. Judging by the amount of time, energy, and emotion that many put into fighting a multitude of battles, ranging from the defense…

The Rule of Love

The traditional confession that Scriptura sacra sui ipsius interpres (“Sacred Scripture is its own interpreter”) presupposes that there is one divine mind behind Scripture, for example. Moreover, Church scholars have traditionally assumed that Scripture’s unity can be discerned in a variety of concepts, motifs, themes and theologies that weave Scripture together. And to speak specifically of the…

Something Else is Going On

The violent portraits of God in the Old Testament are a stumbling block for many. In this short clip, Greg introduces the idea that “something else is going on” in these passages, and that we can begin to see this something else when we put our complete trust in the character of God as fully revealed in…