We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Early Anabaptists and the Centrality of Christ

In a previous post, I wrote about the Christocentric interpretation of the Scriptures espoused by the magisterial Reformers, specifically Luther and Calvin. Their hermeneutic was focused on the work and the offices of Christ, but in my opinion the Anabaptists surpasses their approach because it focused on the person of Christ with an unparalleled emphasis on the call to obey his teachings and follow his example.

In addition, because Luther and Calvin remained within the Constantinian ecclesial paradigm, and thus assumed a just-war perspective on the use of violence, they failed to appreciate the centrality of the enemy-loving non-violence in Jesus’ kingdom ethic. They thus failed to appreciate the full depth of the tension between the Christ who was at the center of their hermeneutic, on the one hand, and OT’s violent divine portraits and violent moral codes, on the other. By contrast, the distinctive emphasis on the enemy-loving, non-violence of Jesus’ teaching and example gave the Christocentric hermeneutic of the Anabaptists a sharper edge as it highlighted the difference between the Old and New Testaments on the use of violence.

I argue that Christ was actually a more significant controlling principle in the Anabaptist hermeneutic and theology than in Luther and Calvin. As Kassen notes, because “Christ was…the center of Scripture” for Anabaptists, “[a]ny specific word in the Bible stands or falls depending upon whether it agrees with Jesus Christ or not.” Hence, “[a]nything which stands in opposition to Christ’s word and life is not God’s word for Christians even if it is in the Bible.” [1] While Anabaptists were as unwavering in their commitment to the plenary inspiration of Scripture as were the magisterial Reformers, they did not hesitate to state that aspects of the OT reflected an incomplete revelation and were no longer binding on Christians.

Another aspect of the Anabaptist approach to Scripture that set them apart was their “hermeneutics of obedience.” The Anabaptists held that understanding and a willingness to obey are closely related. We might compare the way the Bible functioned within the Anabaptist hermeneutic to a Rorschach test: what one discerns when they look at Scripture reflects the condition of their heart at least as much as it reflects what is actually in Scripture.

This conviction, which I introduce here, was by no means an Anabaptist innovation. It’s deeply rooted in Scripture, and one finds it reflected in a variety of ways throughout the Church tradition. What was distinctive about the Anabaptists’ use of this insight, however—and what set them at odds with their Protestant and Catholic contemporaries—was that this insight was fused with their distinctive emphasis on the importance of obeying the teachings and example of Jesus. Some Anabaptists thus insinuated that the reason magisterial church leaders failed to see the centrality of non-violence in Jesus’ teaching and example was not because it is objectively ambiguous but because it’s impossible to correctly interpret Scripture unless one is willing to obey it.

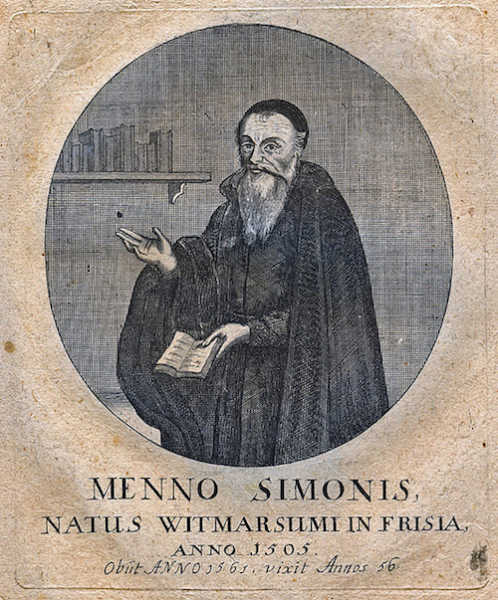

One final aspect of the Christocentric hermeneutic of Anabaptists should be noted. While they were notoriously literalistic when it came to interpreting the NT, there is some evidence that Menno Simons and possibly other Anabaptists were beginning to pick up Origen’s project of reinterpreting or “spiritualizing” aspects of the OT that seemed to contradict the revelation of Christ. Unfortunately, because virtually all of the educated leaders of this fledgling movement were executed before it got off the ground, a distinctly Anabaptist theological reinterpretation of the OT was never explored. We of course cannot say where things might have gone had these leaders survived and/or had a tradition of rigorous theological wrestling with Scripture been established within this movement. Yet, when we consider the centrality of Christ and of non-violence in this movement, together with the fact that some openly acknowledged the contradiction between Christ’s kingdom ethic and aspects of the OT, it doesn’t seem entirely unreasonable to speculate that this group might very well have continued to explore a reinterpretation approach to the problem of violence in the OT, had circumstances allowed for it.

In any event, what I argue in Crucifixion of the Warrior God could justifiably be understood as an attempt to recover and build upon not only the reinterpretation approach of Origen and other early church fathers that was aborted in the fifth century, but also upon the aborted trajectory of early Anabaptists thinking on this problem as well.

[1] W. Klassen, “Bern Debate of 1558: Christ the Center of Scripture,” W. Swartley, ed. Essays on Biblical Interpretation: Anabaptist-Mennonite Perspectives (Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 1984), 106-114 [111].

Photo credit: Stifts- och landsbiblioteket i Skara via Visualhunt.com / CC BY

Category: General

Tags: Anabaptists, Cruciform Theology, Menno Simons

Topics: Biblical Interpretation

Related Reading

Do the Gospels Fabricate Prophetic Fulfillment?

Skeptically-inclined scholars, and especially critics of Christianity, frequently argue that the Gospel authors created mythological portraits of Jesus largely on the basis of OT material they claim Jesus “fulfilled.” In other words, they surveyed the OT and fabricated stories about how Jesus fulfilled those prophecies. In response, it’s hard to deny that there are certain…

Can You Hold a Cruciform Theology AND a Penal Substitution View of Atonement? (podcast)

If you view the cross as the outlet of God’s wrath, then the violence in the Old Testament seems to make perfect sense. Greg responds. Episode 614 http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0614.mp3

Classical Theism’s Unnecessary Paradoxes

The traditional view of God that is embraced by most—what is called “classical theology”—works from the assumption that God’s essential divine nature is atemporal, immutable, and impassible. The Church Fathers fought to articulate and defend the absolute distinction between the Creator and creation and they did this—in a variety of ways—by defining God’s eternal nature…

The Cross and the Witness of Violent Portraits of God

In my previous post I noted that the prevalent contemporary evangelical assumption that the only legitimate meaning of a passage of Scripture is the one the author intended is a rather recent, and very secular, innovation in Church history. It was birthed in the post-Enlightenment era (17th -18th centuries) when secular minded scholars began to…

To What Extent is the Old Testament a Sufficient Revelation of God? (podcast)

Greg considers the relationship between the testaments. Episode 548 http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0548.mp3

Podcast: Has Greg ‘Gone Liberal’ in His Cruciform Hermeneutic?

Greg consoles a disappointed fan and discusses Cruciform Hermeneutics. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0365.mp3