We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Reviewing the Reviews: Rob Grayson (Faith Meets World)

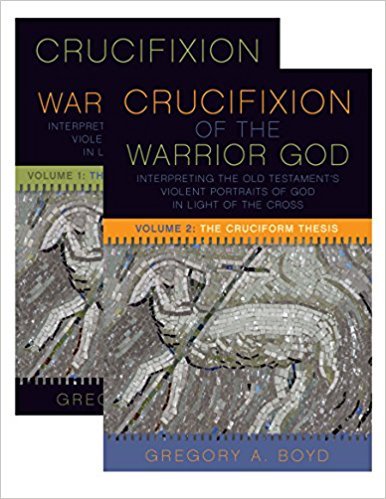

Well folks, Crucifixion of the Warrior God (CWG) has been out three weeks and it’s already in its third printing!

That blows me away! Thank you!!

We’re already getting deeply moving testimonies of how this book – or how messages about the book — are freeing people to better see and trust the beauty of the God revealed in the crucified Christ.

And, of course, people are beginning to write reviews. So I thought it might be fun and informative for me to do an occasional “review of the reviews.” As reviews are brought to my attention, I’ll report on what they say and, most importantly, respond to whatever criticisms and/or objections they raise.

Today I’d like to respond to an excellent three-part review offered by Rob Grayson on his blog, Faith Meets World.

In Part 1 Rob does a good job of setting up the “daunting task” I’m embarking on: namely, “to lay out a hermeneutical and exegetical framework that allows troubling Old Testament texts depicting divine violence to be interpreted in such a way that they faithfully point to Christ on the cross, and thus to God’s essential nature of self-giving love.” He then proceeds to give an accurate, clear, and insightful overview of the three major sections of volume 1.

He does the same for volume 2 in Part 2 though his review of this volume was even more detailed and probing than his review of the first volume. This is because Rob provided an excellent overview of each of the four theses that comprise my Cruciform Thesis. Each of these principles reflects an aspect of the revelation of God on the cross, and each allows us to discern the cross-centered meaning of different aspects of the Old Testament’s violent portraits of God.

In Part 3 Rob provides his assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of this book. He applauds the clarity of my writing and the central place I give the cross. Indeed, he considered the first part of CWG in which I make this case “a joy to read.” Rob also liked the ruthless way I exposed the ugliness of some of the divine portraits in the OT. He says I deserve “great respect for having the cojones to take on this massive issue so willingly, openly and thoroughly.”

Thanks Rob!

But Rob also expresses three concerns about CWG. First, he says that, while I strongly emphasize the divine inspiration of all Scripture, “it never actually becomes totally clear just what [my] model of inspiration is.” This surprised me, since I spend a good amount of time in volume 1 carving out a cross-centered model of inspiration (vol. 1, 481-502). I’ll be interested in seeing if other reviews express the same concern.

The second and “biggest theological concern” Rob has with CWG concerns my concept of “divine withdrawal.” This concept is anchored in the fact that when Jesus stood in our place and bore the judgment of sin that we deserved, the Father merely “delivered him over” to wicked people, operating under the influence of fallen powers, to do what they wanted to do. From this I conclude that God’s judgment never involves God acting violently: it merely involves God withdrawing his presence, which in turn allows sin to run its self-destructive course. This is why Jesus cried out, “Why have you forsaken me?” when he bore the sin and curse of the world.

Rob is concerned that this experienced separation introduces a division into the Trinity. He grants that I argue that it does not, but he says my argument was “difficult to follow and evaluate,” and it left him “with the feeling that it was more of an assertion than a solidly argued and defended case.”

Allow me to try again, because this is actually a very important point. As paradoxical as it sounds, I argue that the point at which the Father and Son experience separation from each other is actually the supreme revelation of their perfect unity. For the unity of the Trinity is other-oriented love, and the only reason the Father and Son are experiencing this separation is because of their perfect other-oriented love for humanity.

In other words, the triune God so loved the fallen world that he was willing to go to the unsurpassable extreme of experiencing his own antithesis – separation from him — as Jesus stood in the place of all condemned sinners. And the unsurpassable extremity to which God was willing to go on our behalf expresses the unsurpassable perfection of the other-oriented love that God eternally is.

This is precisely why the cross is the supreme revelation of God’s perfectly loving character.

Another aspect of the concept of divine withdrawal that Rob takes issue with is that, “if people and groups come under judgment when God withdraws his protective presence, this implies that in all other cases (where people are seemingly not coming under judgment), God is busy ensuring that they remain under his protection.” Do we really want to say that when people experience misfortunes it’s because God is judging them?

As I express in volume 2, chapter 18, my answer is, ABSOLUTELY NOT!!! God’s presence, protection and withdrawal are not the only variables that affect what comes to pass. In reality, there are innumerable unknown variables that affect every particular detail of what comes to pass, including the degree to which people experience good or bad fortunes. The only reason we can assess the disasters that happened to various groups in the Old Testament to be divine judgments is because Scripture (and in some cases Jesus himself) reveals this to us. Without divine revelation, however, we are in no position to judge – as Jesus himself teaches (Lk 13:1-5). (I discuss this at much greater length in Is God to Blame? and Satan and the Problem of Evil.)

Rob’s final concern is that the third of the four principles that comprise the Cruciform Thesis is “The Principle of Cosmic Conflict,” which requires that we believe in the reality of Satan and other principalities and powers. If one doesn’t accept this, Rob notes, there is “a gaping hole in Boyd’s overall thesis.” Rob believes this is a liability, for “within the bounds of Christian orthodoxy, a broad range of views on the nature of evil and the existence or otherwise of angels and demons.” For this reason, he adds, “any robust theology and/or hermeneutic should…be tenable wherever one sits along that spectrum of views.”

Rob is right about the “gaping hole” that denying the reality of angels and demons would create in my hermeneutic. For in this hermeneutic, whenever humans are not the agents that bring about whatever violence is involved in a divine judgment, this violence must be attributed to principalities and powers. And the warrant for this is that principalities and powers were involved in the judgment of sin on the cross. Not only this, but as I argue at length in volume 2, when we assume this posture as we interpret Scripture, we find an abundance of evidence in the narratives themselves and/or elsewhere in Scripture that confirms that it was cosmic agents, not God, that brought about the violence in divine judgments in which humans play no role.

Rob is thus correct in noting that my third principle is not “tenable” with the wide “spectrum of views” that people have on angels and demons. But, while I obviously cannot do so now, I would respond by defending the reality of angels and demons against the “spectrum” of alternative views. And one of the arguments I’d offer in favor of acknowledging their existence is that doing so allows us to affirm the full inspiration of Scripture without accepting that God actually engaged in the violence that OT authors sometimes ascribe to him.

Robs objections aside, he concludes his review by kindly affirming that CWG is “superbly well written, mind-boggling in its breadth and depth, and dazzling in its portrayal of Christ crucified as the acme of God’s self-revelation.” So, despite the fact that Rob does “not see eye to eye” with me “in a number of areas,” he “would not hesitate to recommend CWG as a book that any serious theology enthusiast should have on their shelves.”

Thanks Rob. I appreciate the endorsement!

Category: General

Tags: Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Reviews, Rob Grayson

Topics: Biblical Interpretation

Related Reading

Greg’s Interview on The Christian Transhumanist Podcast

Here is an interview I did for The Christian Transhumanist Podcast that I wanted to share with all of you. Micah Redding and I discuss everything from Relativity Theory to Politics. I think you’ll find it interesting, but I want to offer a word of clarification before you listen. At one point in this interview…

Podcast: Is Open Theism an Accommodation?

Or for that matter is accommodation an accommodation? Greg talks about things that impact God. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0407.mp3

Crucifixion of the Warrior God Update

Well, I’m happy to announce that Crucifixion of the Warrior God is now available for pre-order on Amazon! Like many of you, I found that the clearer I got about the non-violent, self-sacrificial, enemy-embracing love of God revealed in Christ, the more disturbed I became over those portraits of God in the Old Testament that…

The “Third Way”: Seeing God’s Beauty in the Depth of Scripture’s Violent Portraits of God

A publishing house recently sent me an advance copy of a book written by a well known scholar on the topic of the non-violent God revealed in Jesus, asking me to endorse it. (Publishing protocol stipulates that endorsers not critique a book before it’s released, so I will not mention the name of the author…

Does Hebrews 11 Praise Violence? A Response to Paul Copan (#2)

Once or twice a week, as time allows, I will be responding to criticisms of Crucifixion of the Warrior God (CWG) that were raised by Paul Copan in a recent paper that he delivered at the Evangelical Theological Society. In my first post in this series I responded to Copan’s claim that Paul’s quotation from…

What I Am, and Am Not, Doing In These Blog Posts

In this post I’d like to try to help some potentially frustrated readers by explaining what I am, and am not, trying to accomplish in this series on the violent portraits of God in the OT. First let me explain something. My forthcoming book, The Crucifixion of the Warrior God, fleshes out and defends a…