We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

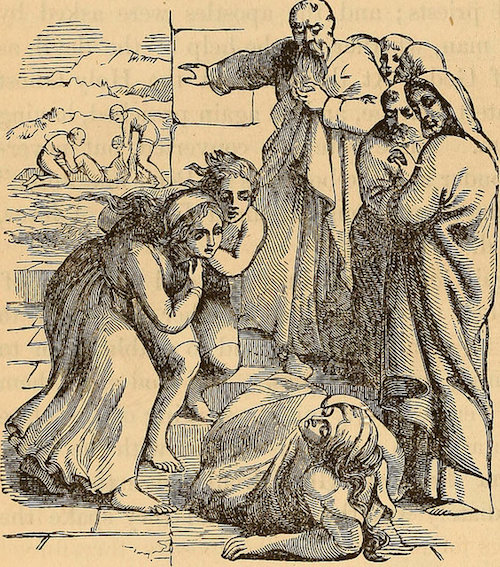

Who Killed Ananias and Sapphira? A Response to Paul Copan (#6)

In his critique of Crucifixion of the Warrior God (CWG), Paul Copan makes a concerted effort to argue that the God revealed in Jesus Christ and witnessed to throughout the NT is not altogether non-violent. One of the passages Copan cites against me is the famous account of Ananias and Sapphira falling down dead immediately after Peter exposes their lie about a donation they made to the kingdom community (Acts 5:1-11). Copan argues that this deceptive couple was “struck down by God, it appears.”

As a matter of fact, the text nowhere says that God slew Ananias and Sapphira. It only “appears” this way to Copan because, like most western believers, he assumes that every supernatural feat that is associated with one of God’s people was carried out by God and therefore reflects God’s will. This is an unwarranted assumption, however. As I argue at length in CWG, the NT shares the widespread ancient conception of divine power as something that God (or a god) could cause to reside in a person, to the point that its use was subject to the person’s own will. I refer to this as the “semi-autonomous conception of divine power.”

We see this illustrated, for example, when Peter encounters a lame man begging for money at the Temple. Peter says, “I do not possess silver and gold, but what I do have I give to you, in the name of Jesus Christ: Walk!” (Acts 3:6). Notice that Peter didn’t pray to God for this man to be healed, as most of us would do today. Rather, Peter knew he had already been given the power to heal people in Jesus name, so he simply commanded the man to start walking. We find the disciples repeating this pattern through the book of Acts (e.g., Acts 9:32-35, etc.).

In responding to infirmities this way, the early Christians were simply following Jesus’ example, for Jesus consistently healed and delivered people not by praying for the Father to heal and deliver them, but simply by speaking healing and deliverance words to them. They also were obeying Jesus’ instructions. For example, Jesus told his disciples; “if you say to this mountain, ‘Be taken up and thrown into the sea,’ and if you do not doubt in your heart, but believe that what you say will come to pass, it will be done” (Mark 11:23). Notice that Jesus did not tell them that if they prayed with faith, God would move the mountain. He rather told them that they themselves will move mountains by speaking to them with faith. The assumption is that the divine power to move mountains resided within them and was released through faith-filled authoritative words.

What is important for us to grasp is that, because this divine power was subject to the will of the person who was endowed with it, people were able to use this power in ways that did not necessarily reflect God’s will. We might think of the divine power that God gave the early disciples along the lines of the power that government gives to police officers. Government of course gives officers this power with the intent that they will use it for the common good. But as we all know, officers occasionally use this power in ways that harm innocent people and conflict with the intention of the government that trusted them with it.

The Bible contains a number of examples of people misusing divine power. For example, God gave Moses the power to use his staff to make water flow from rocks (Exodus 17:6) as well as to perform other supernatural feats. But when Moses once used this divinely empowered staff in an angry way that conflicted with God’s will, the staff still worked (Numbers 20:6-12).

Similarly, when the Apostle Paul instructs the Corinthians about the right way supernatural gifts of the Spirit are to be used in church, he assumes that the way these gifts are manifested is subject to the will of the people who have them. Indeed, he wrote I Corinthians 12-14 precisely because the Corinthians were misusing these supernatural gifts. So, for example, to those who had the gift of prophecy, Paul said: “The spirits of prophets are subject to the control of prophets,” and since “God is not a God of disorder but of peace,” he instructs prophets to use this gift in an orderly way (I Cor 14:32-33).

We find the semi-autonomous conception of divine power in Jesus’ ministry as well. Jesus “knew that the Father had put all things under his power “(Jn 13:3; cf. Matt 11:27), which is why Jesus had to choose to submit his will to the Father and use the divine authority he’d been given in accordance with the Father’s will (Matt 26:42Jn 4:34; 6:38). It was only because the use of divine power was subject to his own will that the devil could tempt him to use this power in ways that conflicted with the Father’s will (Matt 4:1-10).

Moreover, after Peter had lopped off a guard’s ear with his sword, Jesus rebuked him and told him that he could call on “twelve legions of angels” to defend him if that is what he wanted to do, and he assumes that had he done this, the angels would have come (Matt 26:53). And yet, such a display of supernatural power would have conflicted with the Father’s will.

I submit that when Ananias and Sapphira fall down dead in response to Peter’s words, we are seeing semi-autonomous divine power at work. And there is no indication in this passage that Peter’s lethal display of divine power was in accordance with God’s will. As is Luke’s custom, he simply reports what happened without commenting on whether or not this is what should have happened.

As a final word on this passage, I think it’s significant that Ananias and Sapphira had allowed Satan to fill their hearts (Acts 5:3). It’s also significant that the Semitic concept of “curse” had the connotation of lifting protection off of someone to render them vulnerable to hostile agents, whether human or spiritual. In this light, we might understand Peter to be using his apostolic authority to remove whatever divine protection Ananais and Sapphira had, thereby handing them over to the “thief who comes only to kill and to steal and to destroy” (Jn 10:10) and “who holds the power of death” ( Heb 2:14).

Since Jesus came to bring fullness of life, not death (Jn 10:10), and since Jesus is the full revelation of exactly what God is like (Heb 1:3) I submit that it makes better sense to understand Satan to be the agent who brought about the death of Ananais and Sapphira, with Peter’s misuse of his divine authority being the means, than it is to assume their death was an act of God.

Photo by Internet Archive Book Images on VisualHunt.com / No known copyright restrictions

Category: General

Tags: Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Cruciform Theology, Non-Violence, Paul Copan, Power

Topics: Interpreting Violent Pictures and Troubling Behaviors

Verse: Acts 5

Related Reading

A Dialogue with Derek Flood Part 2: Is ALL of the Bible Inspired?

Image by TheRevSteve via Flickr Yesterday, I offered the first part of my response to Flood’s comments regarding my review of his book. Today I’ll finish up my thoughts. Scripture and Its Interpretation Flood confesses that he is confused as to how I can claim that “in the light of Christ, we must reject violent interpretations of Scripture”…

Why NO Violence in Jesus’ Name is Justified

Image by papapico via Flickr On Friday, Greg posted a response to Obama’s speech about religiously-inspired violence. Here are some further thoughts on why violence in the name of Jesus—no matter whether we call it just, redemptive, or defending ourselves—is just another form of kingdom-of-this-world living. The love we are called to trust and emulate is supremely…

Podcast: Is Cruciform Hermeneutics Simply Midrash?

Greg considers whether Cruciform Hermeneutics is just a complicated way of seeing what I want to see in the text, and offers nuanced thought for our more complicated hermeneutical challenges. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0307.mp3

Crucifixion of the Warrior God Update

Well, I’m happy to announce that Crucifixion of the Warrior God is now available for pre-order on Amazon! Like many of you, I found that the clearer I got about the non-violent, self-sacrificial, enemy-embracing love of God revealed in Christ, the more disturbed I became over those portraits of God in the Old Testament that…

Where Does Jesus Affirm the Principle of Accommodation? (podcast)

Greg looks at Jesus as a perfect revelation of God, and considers how Jesus himself reveals an accommodating God in the Old Testament. Episode 598 http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0598.mp3

A Revelation of Beauty Through Ugliness

In my recent post, Getting Honest About the Dark Side of the Bible, I enlisted no less an authority than John Calvin to support my claim that we need to be forthright in acknowledging that some of the portraits of God in the OT are, as he said, “savage” and “barbaric.” What else can we…