We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Does Following Jesus Rule Out Serving in the Military if a War is Just?

Jesus and Military People

Some soldiers responded to the preaching of John the Baptist by asking him what they should do. John gave them some ethical instruction, but, interestingly enough, he didn’t tell them to leave the army (Lk 3:12-13). So too, Jesus praised the faith of a Centurion and healed his servant while not saying a word about the Centurion’s occupation (Mt 8:5-13; Lk 7:1-10). Another Centurion acknowledged Christ as the Son of God at the cross (Mk 15:39) without any negative comment being made about his military involvement. And the first Gentile to receive the Good News of the Gospel was a centurion described as a God-fearing man (Acts 10:22, 34-35). Clearly none of these texts endorse military involvement. But just as clearly, they don’t condemn it. For these and other reasons, most American Christians accept that the New Testament does not forbid serving in the military.

While I respect that people will have differing convictions about this, I must confess that I myself find it impossible to reconcile Jesus’ teaching (and the teaching of the whole New Testament) concerning our call to love our enemies and never return evil with evil with the choice to serve (or not resist being drafted) in the armed forces in a capacity that might require killing someone. The above cited texts show that the Gospel can reach people who serve in the military. They also reveal that John the Baptist, Jesus and the earliest Christians gave military personal “space,” as it were, to work out the implications of their faith vis-à-vis their military service. But I don’t see that they warrant making military service, as a matter of principle, an exception to the New Testament’s teaching that kingdom people are to never return evil with evil.

What About “Just Wars”?

The traditional response to the tension between the New Testament’s teaching and taking up arms to defend one’s country is to argue that fighting in the military is permissible if one’s military is fighting a “just war.” As time honored as this traditional position is, I’m not at all convinced it is adequate.

For one thing, why should kingdom people assume that considerations of whether violence is “justified” or not have any relevance to whether a kingdom person engages in violence? Jesus is our Lord, not a human-constructed notion of justice. And neither Jesus nor any other New Testament author ever qualified their prohibitions on the use of violence. As George Zabelka remarked, the just war theory is “something that Christ never taught or even hinted at.” (1) We are not to resist evildoers or return evil with evil – period. We are to love our enemies, turn the other cheek, bless those who persecute us, pray for people who mistreat us and return evil with good – period. On what grounds can someone insert into this clear, unqualified teaching the massive exception clause – “unless violence is ‘justified’”?

Many have argued that such grounds are found in Romans 13. Since Paul in this passage grants that the authority of government ultimately comes from God and that God uses it to punish wrongdoers (Rom. 13:1-5), it seems permissible for Christians to participate in this violent activity, they argue, at least when the Christian is sure it is “just.” The argument is strained on several accounts, however.

First, while Paul encourages Christians to be subject to whatever sword-wielding authorities they find themselves under, nothing in this passage suggests the Christians should participate in the government’s sword wielding activity. Second, Romans 13 must be read as a continuation of Romans 12 in which Paul tells disciples to (among other things) “bless those who persecute you”( vs. 14); “do not repay anyone evil for evil” (vs. 17); and especially “never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord’” (vs. 19). Leaving vengeance to God, we are to instead feed our enemies when they are hungry and give them water when they are thirsty (vs. 20). Instead of being “overcome by evil,” we are to “overcome evil with good” (vs. 21).

Now, in the next several verses, Paul specifies that sword-wielding authorities are one means by which God executes vengeance (13:4). Since this is the very same vengeance disciples were just forbidden to exercise (12:19, ekdikeo) it seems to follow, as Yoder argues, that the “vengeance” that is recognized as being within providential control when exercised by government is the same “vengeance” that Christians are told not to exercise. (2) In other words, we may acknowledge that in certain circumstances authorities carry out a good function in wielding the sword against wrongdoers, but that doesn’t mean people who are committed to following Jesus should participate in it. Rather, it seems we are to leave such matters to God, who uses sword-wielding authorities to carry out his will in society.

How do we know when a war “just”?

Thirdly, even if one concludes that a follower of Jesus may participate in violence if it is “just,” we have to wonder how a kingdom person could confidently determine whether a war is “just” or not. Few battles have been fought in which both sides didn’t believe their violence was “justified.” The reality is that the criteria one uses to determine what is and is not “just” is largely a function of where one is born and how one is raised. How much confidence should a kingdom of God citizen place in that?

For example, unlike most other people groups throughout history and yet today, modern Americans tend to view personal and political freedom as an important criteria to help determine whether a war is “just” or not. We kill and die for our freedom and the freedom of others. But why should a kingdom person think killing for this reason is a legitimate exception to the New Testament’s command to love and bless enemies? Can they be certain God holds this opinion?

Of course it seems obvious to most Americans that killing to defend and promote freedom is justified, but fundamental aspects of one’s culture always seem obviously right to people embedded in the culture. This criterion certainly hasn’t been obvious to most people throughout history, including most Christians throughout history. And it’s “obviously” wrong to many non-Americans — including Christians — around the globe today. Even more importantly, it certainly isn’t obvious in Scripture. In this light, kingdom people in all countries need to seriously examine the extent to which the ideal that leads them to think a war is or is not “just” is the result of their own cultural conditioning.

Assessing this is no easy matter. It helps to be mindful of the fact that the person you may end up killing in war probably believes, as strongly as you, that they are also fighting for a “just” cause. It also helps to consider the possibility that they are disciples of Jesus just like you, perhaps even mistakenly thinking their cause is a function of their discipleship just as some American soldiers believe. You have to believe that all of their thinking is merely the result of their cultural conditioning — for you obviously believe they’re wrong to the point of being willing to kill them — while also being convinced that your own thinking is not the result of cultural conditioning. Can you be absolutely sure of this? Your fidelity to the kingdom of God, your life and the lives of others are on the line.

But suppose, for the sake of argument, we grant that political freedom is a just cause worth killing and dying for. This doesn’t yet settle the matter for a kingdom person contemplating enlisting in war (or not resisting being drafted into war), for one has to further appreciate that there are many other variables alongside the central criterion of justice that affect whether or not a particular war is “just.”

Do you know – can you know – the myriad of personal, social, political and historical factors that have led to any particular conflict and that bear upon whether or not it is “justified?” For example, do you truly understand all the reasons your enemy gives for going to war against your nation, and are you certain they are altogether illegitimate? Are you certain your government has sought out all possible non-violent means of resolving the conflict before deciding to take up arms? Are you certain the information you’ve been given about a war is complete, accurate and objective? Do you know the real motivation of the leaders who will be commanding you to kill or be killed for “the cause” (as opposed to what the national propaganda may have communicated)? Are you certain that the ultimate motivation isn’t financial or political gain for certain people in high places? Are you certain that the war isn’t in part motivated by personal grievances and/or isn’t being done simply to support or advance the already extravagant lifestyle of most Americans? Given what we know about the corrupting influence of demonic powers in all nations, and given what we know about how the American government (like all other governments) has at times mislead the public about what was “really” going on in the past (e.g. the Vietnam war), these questions must be wrestled with seriously.

Yet, even these questions do not resolve the issue for a kingdom person, for a kingdom person must know not only that a war is “justified” but that each and every particular battle they fight, and the loss of each and every life they may snuff out, is justified. However “justified” a war may be, commanders often make poor decisions about particular battles they engage in that are not “just” and that gratuitously waste innocent lives. While militaries sometimes take actions against officers who have their troops engage in unnecessary violence, the possibility (and even inevitability) of such unjust activity is typically considered “acceptable risk” so long as the overall war is “just.” But on what grounds should a person who places loyalty to Jesus over their commander accept this reasoning?

The fact that a war was “justified” means nothing to the innocent lives that are wasted, and the question is: How can a kingdom person be certain in each instance that they are not participating in the unnecessary and unjust shedding of innocent blood? It’s questionable enough that a follower of Jesus would kill their national enemy rather than bless them simply because it’s in the interest of their nation for them to do so. But what are we to think of the possibility that a follower of Jesus would kill someone who is not an enemy simply because someone higher in rank told them to?

The tragic reality is that most people contemplating entering the armed forces (or contemplating not refusing the draft), whether they be American or (say) Iraqi, North Korean or Chinese, don’t seriously ask these sorts of questions. Out of their cultural conditioning, most simply assume their authorities are trustworthy, that their cause is “justified,” and that each person they are told to kill is a justified killing. They unquestioningly believe the propaganda and obey the commands they’re given. Throughout history, soldiers have for the most part been the unquestioning pawns of ambitious, egotistical rulers and obedient executors of their superior’s commands. They were hired assassins who killed because someone told them to and their cultural conditioning made it “obvious” to them that it was a good and noble thing to do. So it has been for ages, and so it will be so long as people and nations operate out of their own self-interest.

The Kingdom Alternative

But there is an alternative to this ceaseless, bloody, merry-go-round: it is the kingdom of God. To belong to this kingdom is to crucify the fleshly desire to live out of self-interest and tribal interest and to thus crucify the fallen impulse to protect these interests through violence. To belong to this revolutionary kingdom is to purge your heart of “all bitterness and wrath and anger and wrangling and slander, together with all malice” (Eph 4:31)—however “justified” and understandable these sentiments might be. To belong to this counter-kingdom is to “live in love, as Christ loved you and gave his life for you” (Eph 5:1-2). It is to live the life of Jesus Christ, the life that manifests the truth that it is better to serve than to be served, and better to die than to kill. It is, therefore, to opt out of the kingdom-of-the-world war machine and manifest a radically different, beautiful, loving way of life. To refuse to kill for patriotic reasons is to show “we actually take our identity in Christ more seriously than our identity with the empire, the nation-state, or the ethnic terror cell whence we come,” as Lee Camp says.

Hence, while I respect the sincerity and courage of Christians who may disagree with me and feel it their duty to defend their country with violence, I myself honestly see no way to condone a Christian’s decision to kill on behalf of any country.

Endnotes

(1) G. Zebelka, “I Was Told It Was Necessary,” [Interview] Sojourners, 9/8/80, p.14.

(2) J. Yoder, The Politics of Jesus (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2nd ed. 1994 [1972]), 198. See also Hays, Moral Vision, 320-31.

Further Reading

Beller, K. H. Chase, Great Peacemakers (LTS 2008)

Brimlow, R. What About Hitler? (Brazos, 2006)

Eller, V. War & Peace (Wipf & Stock, 2003 [1981])

Roth, J. Choosing Against War (GoodBooks, 2002)

Trocme, A. Jesus and the NonViolent Revolution (Wipf & Stock, 2003 [1973])

Trznya, T. Blessed are the Pacifists (Herald, 2006)

Category: Q&A

Tags: Kingdom Living, Non-Violence, Q&A

Topics: Enemy-Loving Non-Violence, Ethical, Cultural and Political Issues

Related Reading

Christians and Creation Care

Image by Ali Inay While the mustard seed of the Kingdom has been planted, it obviously hasn’t yet taken over the entire garden (Matt 13:31-42). We continue to live in an oppressed, corrupted world. We live in the tension between the “already” and the “not yet.” Not only this, but we who are the appointed landlords…

Why do you argue that discipleship and politics are rooted in opposite attitudes?

Question. At a recent conference I heard you argue against the idea that there could ever be a distinctly “Christian” political position by contending that political disputes are premised on a claim to superiority while discipleship is fundamentally rooted in humility. I don’t think I get what you mean. Can you explain this? Answer: In…

Can you have an Anabaptist Mega-Church?

Several times over the last few years I’ve heard statements like this: “Boyd may embrace an Anabaptist theology, but his church (Woodland Hills) cannot be, by definition, an Anabaptist church because an Anabaptist church can’t be a mega-church.” I’ve heard similar things about our sister church, The Meeting House, in Toronto Canada. The reasoning behind these…

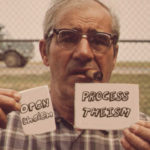

Process Theology & Open Theism: What’s the Difference?

Question: When ReKnew talks about Open Theism is it a mistake for people to equate it with Process theology, and if so what are the defining differences? I guess I am starting to lean toward Dr. Boyd’s thoughts for all things theologically egg-heady, so I thought I would ask the question. Your ministry has been freeing…

What Would You Propose To Do To Stop Hitler?

In this episode Greg talks about the Christian call to love our enemies–even Hitler. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0007.mp3

How Much Is Enough?

Richard Beck over at Experimental Theology wrote a reflection on insights he gained from the book How Much is Enough?: Money and the Good Life by Robert Skidelsky and Edward Skidelsky. He points out how the advent of money changed the way we view our needs and made it easier to hoard without noticing it. It’s a…