We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

How To Talk about Theology

Social media is full of theological debate. Theological arguments that formerly took months or even years to get in print, now only takes the time to write a post or 140 characters and click “publish.” Social media is great in that it makes space for all of our voices. However, it also seems to elevate every theological argument to the same level of importance. Two things often result. First, with so many voices in play, the theological banter can eventually sound like static, too much noise that hinders us from seeing what’s important. Secondly, the rhetoric is often short, terse, and lacks nuance, therefore resulting in embattled language that sets up the conversation in “either/or” categories.

How do we sort out the voices? How do we weigh what is important to discuss and what needs to be set aside? How do we have conversations with others without viewing them as “the enemy.” In Benefit of the Doubt, Greg offers a model for how we can think theologically about the various issues and weigh the importance of the various debates. In addition, this model helps to facilitate conversations with others with whom we disagree without having to use “either/or” language. Here is Greg’s model for talking about theology:

____________________

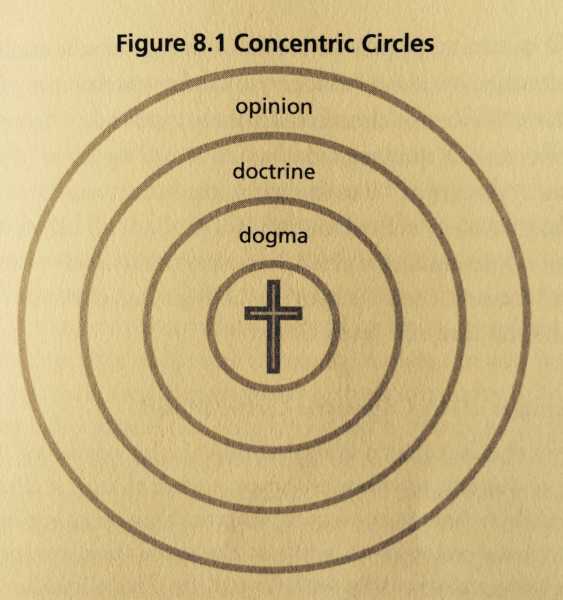

I envision my beliefs in the form of circles that are oriented around a single center. And the center is Jesus Christ, the one who perfectly reveals to us the love God eternally is, who perfectly embodies the love God has for us, who perfectly models the love we’re to have toward others, and who is the means by which we enter into a loving, covenantal, faith-based relationship with God. …

With this center always in view, I assess my beliefs in terms of their relative importance. I thus envision three concentric circles surrounding the center. The proximity of each circle to the center reflects its relative importance.

Because all followers of Jesus are called to belong to his body, the church, I believe we must carry out our assessment of our beliefs in dialogue with the historic-orthodox church tradition. For this reason, I place in the innermost ring those beliefs that have traditionally been understood to constitute orthodox Christianity. These are sometimes referred to as the “dogma” of the church, and they are reflected in our foundational ecumenical creeds (e.g., the Nicene and the Apostles’ Creed). The belief that God is a Trinity, that Christ is fully God and fully human, and that the world is created and governed by God are examples of the dogmas that compose the innermost ring.

In the next ring I place beliefs that orthodox Christians have always espoused, but over which there has been some disagreement. These are the different doctrines that distinguish various denominations, and most derive from different ways of interpreting the dogmas found in the ring just outside the core circle. For example, orthodox Christians have always believed that God governs the world, …, but at least from the fourth century on, there has been no uniform agreement as to how God does this. Some have held that God governs by controlling every event in history, while others have held that God has given a degree of free will to humans and angels. To distinguish this circle from the innermost circle, I would label the beliefs that compose this circle “doctrine.”

Finally, in the outermost ring I place beliefs that individual Christians have occasionally espoused but that have never gained widespread support and that have rarely been adopted by a recognized church body. While the circle of “doctrine” comprises the different ways Christians have interpreted “dogma,” this third circle usually comprises different ways of interpreting particular doctrines. Two examples of the innumerable beliefs that could be placed in the circle would be the “gap theory” that posits a long interval between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2 as a way of reconciling this creation account with evolution, and the “Open View of the future” that holds that the future is not fully settled. To distinguish the circle from the circle of “doctrine,” I would label it “opinion.”

There is of course plenty of room for disagreement over the details of this paradigm of three concentric circles surrounding the center, Jesus Christ. While the church uniformly agrees on what constitutes dogma, one person may regard a belief to be “opinion” that another regards as a “doctrine.” But the most important aspect of this paradigm is that they currently articulate the fact that not all beliefs are equally important while making it clear that everything revolves around, and is oriented toward, the all important, life-giving, covenantal relationship with God through Jesus Christ.

Beyond the fact that it is more biblical, this model of faith has an important number of distinct advantages. Among other things, it allows people to adjust their beliefs to accommodate their ongoing intellectual and spiritual development while at the same time grounding them in a life-giving relationship with Christ. It’s flexibility allows people, and even encourages them, to fearlessly and honestly wrestle with whatever issues come their way and, so long as their life remains anchored in Christ, to do so in a non-defensive and objective way. For the same reason, this model empowers Christians to discuss and debate issues with other Christians or with nonbelievers in loving, non-defensive, and rational ways (170-172).

Category: General

Tags: Benefit of the Doubt, Cruciform Theology, Debate, Problem of Evil, Social Media, Theology

Topics: Theological Method

Related Reading

The Cruciform Center Part 4: How Revelation Reveals a Cruciform God

I’ve been arguing that, while everything Jesus did and taught revealed God, the character of the God he reveals is most perfectly expressed by his loving sacrifice on the cross. Our theology and our reading of Scripture should therefore not merely be “Christocentric”: it should be “crucicentric.” My claim, which I will attempt to demonstrate…

Part 4: An Alternative Cross-Centered Approach

Image by Karl Pang via Flickr As I mentioned in Part II of this review, I am deeply appreciative of the fact that Flood grasps the centrality of enemy-loving non-violence in Jesus’ revelation of God. And while many, if not most, of the depictions of Yahweh in the Old Testament are consistent with this revelation, I…

Lighten Up: Ball and Chain Theology

Let’s not allow our theology to keep us from encountering one another in meaningful ways.

Podcast: How Do You Make Sense of the Killing of Ananias and Sapphira?

Greg considers: “Who actually killed Ananias and Sapphira.” This ancient murder mystery has enormous theological implications! Listen as Inspector Boyd hunts for clues and builds a most compelling case. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0108.mp3 Photo credit: jean louis mazieres via VisualHunt.com / CC BY-NC-SA

Free Will: The origin of evil

In this continuing series on free will, Greg discusses how evil can only be accounted for if we acknowledge free will. This is especially true if you believe that God is good.

To What Extent is the Old Testament a Sufficient Revelation of God? (podcast)

Greg considers the relationship between the testaments. Episode 548 http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0548.mp3