We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

How Should We Do Theology?

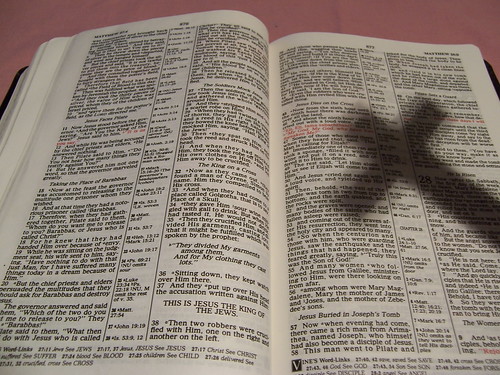

A central debate among evangelical theologians concerns the question of theological method. In other words, how should we “do” theology?

All evangelical Christians believe the Bible is God’s inspired revelation. Thus, evangelicals agree that Scripture must form the foundation for theological thought. But Scripture is not the only factor to consider when doing theology. Many evangelicals have adopted the Wesleyan quadrilateral (named after the eighteenth-century British revivalist and founder of Methodism, John Wesley) as a way to explain the various sources of theology and how they relate to each other. The quadrilateral, as the name suggests, presents theology as rooted in four sources: Scripture, Church tradition, reason, and experience. Scripture is viewed as the foundation of theology, with each of the other three aspects helping to clarify and interpret Scripture in a faithful manner for the purpose of doing theology.

The debate arises when the question is asked: How are we to balance the four aspects of the quadrilateral, and to what degree do tradition, reason, and experience shape and determine our understanding of the Bible? Although there is a spectrum of views on how to answer this question, two basic models can be described as follows.

According to the traditional evangelical model, the task of theology is to systematize and articulate the doctrinal truths found in the Bible. The emphasis is on the Bible as the unchanging, transcultural revelation of God. In the words of Carl F. H. Henry, “Divine revelation is the source of all truth, the truth of Christianity included…The task of Christian theology is to exhibit the content of biblical revelation as an orderly whole.” (C.Henry, God, Revelation, and Authority, vol. 1 [Waco: Word, 1976], 215). This view of the theological task is rooted in an understanding of the Bible known as propositionalism. For those who hold to a propositionalist understanding, the Bible is seen primarily as containing and offering information about God. In Henry’s words, “Scriptures contain a body of divinely given information actually expressed or capable of being expressed in propositions.”(Ibid., vol. 3, 457).

In contrast to the traditional view is the postfoundationalist evangelical model. Like other expressions of the postmodern perspective, the postfoundationalist approach emphasizes the culturally conditioned nature of all human intellectual enterprises—theology included. Simply put, the postfoundationalist method, while still recognizing the Bible as the primary theological norm, places greater emphasis on the way human reason and experience structure and shape any given theology. Stanley Grenz expresses this conviction when he writes that “the categories we employ in our theology are by necessity culturally and historically conditioned, and as theologians each of us is both ‘a child of the times’ and a communicator to those times.”(S. Grenz, Revisioning Evangelical Theology: A Fresh Agenda for the Twenty-first Century [IVP, 1993] 83).

While the fundamental Christian faith-commitment does not change, the conceptualization and articulation of this faith-commitment does change over time and across cultures. Thus, there is no expectation of ever arriving at a single evangelical “theology”; there will always be a number of diverse evangelical “theologies.” This is true both because God, the primary object of theology, is beyond any human system of thought, and because every human theological system will always be conditioned by its cultural context.

From a postfoundationalist perspective, the Bible is the inspired narrative of the saving acts and message of God. This means that the central locus of revelation is the narrative itself, not a set of propositions that can be distilled from and expressed outside of that narrative. The truths of God and his character are expressed in the unchanging story of Christian faith. A systematic theology, then, being necessarily and dramatically shaped by the components of human reason and experience, is always a culturally conditioned conceptualization and articulation of the implications of the unchanging biblical narrative for a particular people at a particular time and place.

For my part, I am convinced the traditional evangelical model of treating Scripture as a body of timeless truths is misguided. With the postfoundationalist camp, I see the Bible as an inspired narrative of God’s saving acts in history. But I am also wary of the postfoundationalist camp inasmuch as it can easily slip into a relativism that undermines the absoluteness of the truth claims of the Christian faith. Postfoundationalism can be interpreted to mean there is no foundation. In this case, people can never claim that the narrative (worldview) they choose to embrace and live by actually reflects the way things are. We can testify to the value the Christian story holds for us, but we cannot say it is more true than any other story.

I thus hold that Christian theology needs a foundation by which its truth claims can be anchored and assessed. Unlike the traditional evangelical model of Carl Henry, I do not see this foundation as being a body of revealed information. I rather see this foundation as being the historical witness to Jesus Christ as the definitive revelation of God. All theology is to be centered on Christ and epistemically anchored in historical considerations that ground the claim that he was, and is, the revelation of God to humanity. (On this, see P. Eddy and G. Boyd, The Jesus Legend [IVP, 2007]). The whole of the biblical narrative is centered on him and finds its legitimization in him.

Category: General

Tags: Approaches to Theology, Bible, Revelation, Scripture, Theology, Wesleyan Quadrilateral

Topics: Theological Method

Related Reading

The Cross and the Witness of Violent Portraits of God

In my previous post I noted that the prevalent contemporary evangelical assumption that the only legitimate meaning of a passage of Scripture is the one the author intended is a rather recent, and very secular, innovation in Church history. It was birthed in the post-Enlightenment era (17th -18th centuries) when secular minded scholars began to…

The One True Image of God: God’s Self-Portrait, Part 4

This point is emphasized throughout the New Testament because, if we don’t get this, we are left to our own imaginations about God, and we’ll draw from a multitude of different sources to construct a mental picture of God that will, to one degree or another, fall short of the beauty of the true God…

What About the Contradictions Found in the Gospels?

It’s quite common for people to question the veracity of the Gospels because there are contradictions between them. In fact, an interaction between Steven Colbert and Bart Erhman, a scholar who makes a big deal of these contradictions, has become quite popular. While Colbert’s comedic response is entertaining, we must say more. And Greg has done…

Crucifixion of the Warrior God Update

Well, I’m happy to announce that Crucifixion of the Warrior God is now available for pre-order on Amazon! Like many of you, I found that the clearer I got about the non-violent, self-sacrificial, enemy-embracing love of God revealed in Christ, the more disturbed I became over those portraits of God in the Old Testament that…

The Cruciform Center Part 4: How Revelation Reveals a Cruciform God

I’ve been arguing that, while everything Jesus did and taught revealed God, the character of the God he reveals is most perfectly expressed by his loving sacrifice on the cross. Our theology and our reading of Scripture should therefore not merely be “Christocentric”: it should be “crucicentric.” My claim, which I will attempt to demonstrate…

For the Bible Tells Me So?

Oh, those pesky fundamentalists are at it again. Should it be legal for parents to execute their rebellious children based upon Deut 21:18-21? This guy thinks so. And he’s a Bible-believing Christian who is a candidate for his state’s legislature, so it must be true, right? Of course, under this proposed legislation, parents would need to…