We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

How To Talk about Theology

Social media is full of theological debate. Theological arguments that formerly took months or even years to get in print, now only takes the time to write a post or 140 characters and click “publish.” Social media is great in that it makes space for all of our voices. However, it also seems to elevate every theological argument to the same level of importance. Two things often result. First, with so many voices in play, the theological banter can eventually sound like static, too much noise that hinders us from seeing what’s important. Secondly, the rhetoric is often short, terse, and lacks nuance, therefore resulting in embattled language that sets up the conversation in “either/or” categories.

How do we sort out the voices? How do we weigh what is important to discuss and what needs to be set aside? How do we have conversations with others without viewing them as “the enemy.” In Benefit of the Doubt, Greg offers a model for how we can think theologically about the various issues and weigh the importance of the various debates. In addition, this model helps to facilitate conversations with others with whom we disagree without having to use “either/or” language. Here is Greg’s model for talking about theology:

____________________

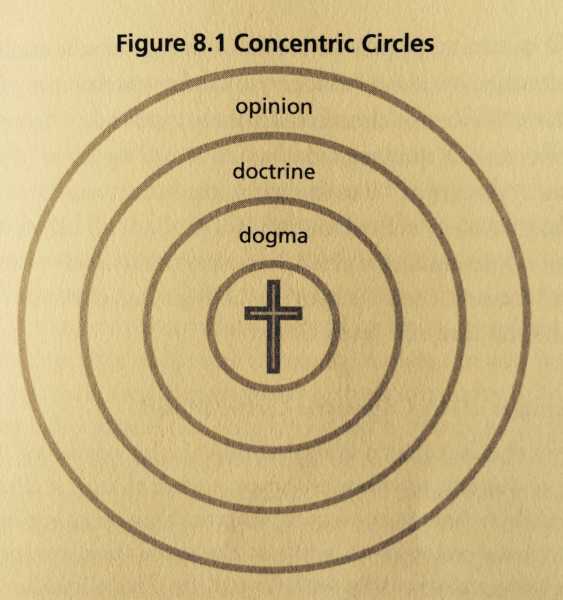

I envision my beliefs in the form of circles that are oriented around a single center. And the center is Jesus Christ, the one who perfectly reveals to us the love God eternally is, who perfectly embodies the love God has for us, who perfectly models the love we’re to have toward others, and who is the means by which we enter into a loving, covenantal, faith-based relationship with God. …

With this center always in view, I assess my beliefs in terms of their relative importance. I thus envision three concentric circles surrounding the center. The proximity of each circle to the center reflects its relative importance.

Because all followers of Jesus are called to belong to his body, the church, I believe we must carry out our assessment of our beliefs in dialogue with the historic-orthodox church tradition. For this reason, I place in the innermost ring those beliefs that have traditionally been understood to constitute orthodox Christianity. These are sometimes referred to as the “dogma” of the church, and they are reflected in our foundational ecumenical creeds (e.g., the Nicene and the Apostles’ Creed). The belief that God is a Trinity, that Christ is fully God and fully human, and that the world is created and governed by God are examples of the dogmas that compose the innermost ring.

In the next ring I place beliefs that orthodox Christians have always espoused, but over which there has been some disagreement. These are the different doctrines that distinguish various denominations, and most derive from different ways of interpreting the dogmas found in the ring just outside the core circle. For example, orthodox Christians have always believed that God governs the world, …, but at least from the fourth century on, there has been no uniform agreement as to how God does this. Some have held that God governs by controlling every event in history, while others have held that God has given a degree of free will to humans and angels. To distinguish this circle from the innermost circle, I would label the beliefs that compose this circle “doctrine.”

Finally, in the outermost ring I place beliefs that individual Christians have occasionally espoused but that have never gained widespread support and that have rarely been adopted by a recognized church body. While the circle of “doctrine” comprises the different ways Christians have interpreted “dogma,” this third circle usually comprises different ways of interpreting particular doctrines. Two examples of the innumerable beliefs that could be placed in the circle would be the “gap theory” that posits a long interval between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2 as a way of reconciling this creation account with evolution, and the “Open View of the future” that holds that the future is not fully settled. To distinguish the circle from the circle of “doctrine,” I would label it “opinion.”

There is of course plenty of room for disagreement over the details of this paradigm of three concentric circles surrounding the center, Jesus Christ. While the church uniformly agrees on what constitutes dogma, one person may regard a belief to be “opinion” that another regards as a “doctrine.” But the most important aspect of this paradigm is that they currently articulate the fact that not all beliefs are equally important while making it clear that everything revolves around, and is oriented toward, the all important, life-giving, covenantal relationship with God through Jesus Christ.

Beyond the fact that it is more biblical, this model of faith has an important number of distinct advantages. Among other things, it allows people to adjust their beliefs to accommodate their ongoing intellectual and spiritual development while at the same time grounding them in a life-giving relationship with Christ. It’s flexibility allows people, and even encourages them, to fearlessly and honestly wrestle with whatever issues come their way and, so long as their life remains anchored in Christ, to do so in a non-defensive and objective way. For the same reason, this model empowers Christians to discuss and debate issues with other Christians or with nonbelievers in loving, non-defensive, and rational ways (170-172).

Category: General

Tags: Benefit of the Doubt, Cruciform Theology, Debate, Problem of Evil, Social Media, Theology

Topics: Theological Method

Related Reading

The Greatest Mystery of the Christian Faith

God has always been willing to stoop to accommodate the fallen state of his covenant people in order to remain in a transforming relationship with them and in order to continue to further his sovereign purposes through them. Out of love for humankind, Scripture tells us, Jesus emptied himself of his divine prerogatives, set aside…

Cruciform Aikido Pt 1: Jesus and the Violent God

Note: Today, we are beginning a 4-part series on the subject of divine judgement called “Cruciform Aikido.” We will be publishing this once a week alongside Greg’s introduction to ReKnew series. When most people think of God judging sinners, they imagine an angry God who acts violently as he vents his wrath and brings vengeance on people.…

Satan or God: Who Tempted David to Sin?

The author of 2 Samuel says that Yahweh caused David to sin by taking a census of his military personnel (2 Sam 24:1) while the author of 1 Chronicles attributes this temptation to Satan (1 Chr 21:1). It is clear that the author of 2 Samuel had no problem accepting that Yahweh was capable of…

The Centrality of Christ in Hebrews, Part 1

The intense Christocentricity that the New Testament writers embrace is nowhere more clearly and consistently illustrated than in the book of Hebrews. Throughout this work we find a repeated emphasis on the many ways the revelation given to us in Christ surpasses that of the Old Testament. The author begins by stressing how the revelation…

How NOT to be Christ-Centered: A Review of God With Us – Part II

In Part I of my review of Scott Oliphint’s God With Us we saw that Oliphint is attempting to reframe divine accommodation in a Christ-centerd way. Yet, while he affirms that “Christ is the quintessential revelation of God,” he went on to espouse a classical view of God that was anchored in God’s “aseity,” not…

Would God Kill a Baby To Teach Parents a Lesson?

Question: We have a group of guys that are going through your book “Is God to Blame” and a question came up that I would be curious how you would look at it. In the beginning of the book you ask the question “do you really think that God kills babies to teach parents a lesson?”…