We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

The Point of the Book of Job

The point of the book of Job is to teach us that the mystery of evil is a mystery of a war-torn and unfathomably complex creation, not the mystery of God’s all-controlling will.

Given how Christians are yet inclined to look for a divine reason behind catastrophes and personal tragedies, I think it’s a point we have yet to learn.

In this essay I’ll flesh out my reading of this incredibly profound book.

The Prologue

The genre of this book is epic poetry. As is customary with epic poems, it begins with a prologue that sets up the story line (chs 1-2). In Job, this prologue serves as a literary device to give the reader a perspective that the characters in the story lack. This is important, for the point of the whole narrative, we shall see, is to expose the vast ignorance of the characters involved.

The prologue centers on a chance dialogue that takes place between God and a certain rebel angel called (literally in Hebrew) “the satan,” meaning “the adversary.” At this early stage of revelation (many scholars believe that Job is the oldest book in the Bible) this figure had not yet acquired “Satan” as a personal name. Though he is not yet seen as the altogether sinister cosmic force we find him to be in later biblical revelation, he is nevertheless depicted as somewhat outside of, and in opposition to, Yahweh’s authority.

The rebellious nature of the satan alluded to in the prologue is evidenced by the fact that he is not one of the invited guests at the council meeting of the “sons of God” (Job 1:6-7; 2:1). The chance nature of the confrontation between the satan and Yahweh is captured in the fact that Yahweh seems surprised to see him. He has to ask him, “Where have you been?” To which the satan answers, “From going to and fro on the earth, and from walking up and down on it” (Job 1:7; 2:2). We see that the satan is not a being who operates under Yahweh’s authority, as do the regular council members. He was not carrying out assignments from God. Rather, he randomly walks to and fro on the earth on his own. Indeed, Yahweh has to protect people from him (1:10).

The satan assails God’s wisdom and character in running the universe by alleging that people only serve him because of what they get out of it. God protects them from him and blesses them in other ways. Their obedience, he is suggesting, isn’t really a free choice. There is no genuine virtue in the world, the satan is claiming. There are only self-serving bargains, and obedience for the sake of being protected and blessed is one of them. Hence, true holiness and virtuous obedience are an illusion. Take away a person’s protection, the satan insists, and let him have his way with people, and they will stop living for God (Job 1:9-11; 2:4-5).

The adversary, we see, was assailing God’s integrity and wisdom in overseeing the creation. He was, in effect, accusing him of being a Machiavellian ruler. In the context of this narrative, it was an assault that could only be refuted by being put to a test.

Had Yahweh simply forced the satan into silence, without proving him wrong, it would have simply confirmed the accuracy of the satan’s charge. It would have shown that there is no integrity or wisdom in how God runs the universe after all. There is only the exercise of power, used to manipulate beings into obeying him. People serve God only as a bargain, not out of genuine love.

No, the challenge had to be answered by having it put to a test. The most righteous man on the earth was thus chosen to be tested. If Job failed, the narrative suggests, then the satan will have made his point. If he succeeded, however, then God’s wisdom and integrity in running the cosmos will have been vindicated. Hence, the protective fence around Job is removed and the satan is allowed to afflict him.

One final word about the prologue should be noted before we discuss the body of this work. Since we are dealing with an epic poem, most Old Testament scholars agree that it is misguided to press this prologue for literal details about God’s general relationship to Satan. The literary point of the prologue is not to answer questions like, “Does Satan always have to get specific permission every time he does something?,” or “Is every affliction the result of a heavenly challenge to God’s authority?” As with Jesus’ parables, the central point of the prologue is the only point the reader is supposed to get. We misunderstand Jesus’ parable about Lazarus, for example, if we wonder whether people in hell can literally talk to people in paradise (Lk 16:19-31). This is simply a literary prop to allow Jesus to make the point that if people don’t repent now on the basis of the revelation they’ve already received, they wouldn’t respond even if someone (like Larzarus) came back from the dead (Lk 16:31).

So it is in the prologue of Job. The purpose of the prologue is to set up a specific episode that will vindicate God’s wisdom and integrity. It serves this function by bringing the readers in on the satan’s assault on God’s wisdom and character while leaving the actors in this drama in the dark. It thus highlights the ignorance of the actors as they each put forth their theological perspectives. It shows that things happen to people on earth because of chance encounters in heaven, about which these people know nothing. And, as we shall see, this is the central point of the whole epic drama.

Is Job to Blame ?

The bulk of the narrative is formed around Job’s conversations with his friends. Though his friends initially do the right thing and sit in silence (Job 2:11-13), when Job begins to express his pain, his friends begin to correct his theology. Sounding remarkably like many Christians today when they confront people in pain, and illustrating perfectly the complaint the satan originally raised against God, his friends insist that since God is perfectly just, Job must deserve what God is dishing out to him. People who serve God are protected and blessed, they assume. So they feel justified in concluding that those who clearly have not been protected and are not being blessed — people like Job — simply haven’t been serving God. They are, therefore, being disciplined.

Eliphaz is representative of this sort of blueprint wisdom when he says to Job:

“Think now, who that was innocent ever perished?

Or where were the upright cut off?

As I have seen, those who plow iniquity

and sow trouble reap the same.

By the breath of God they perish,

and by the blast of his anger they are consumed. ” (Job 4:7-9)

Of course, we all know that innocent and upright people are “cut off” all the time. Sometimes babies die in the birthing process! Eliphaz’s statements illustrate the remarkable capacity some people have to ignore reality for the sake of preserving a formulaic theology that serves their own purposes. As Job himself recognizes, his friends put forth their theology as a way of reassuring themselves that what happened to Job couldn’t happen to them (Job 6:20-21). They were theologizing out of their own fears and to meet their own needs, not as a way of ministering to Job in the midst of his needs. Surely the universe can’t be as arbitrary as it seems, Job’s friends insist. And in the process of reassuring themselves, they are indicting Job, for his unfortunate life doesn’t conform to his friends’ wishful-thinking theology.

Nevertheless, Eliphaz continues, since God always does the right thing, and since both Job and his friends are assuming that God is directly behind what is happening to Job, Job should actually be happy about his plight. For it means that God is disciplining him for a good reason:

“How happy is the one whom God reproves;

therefore do not despise the discipline of the Almighty.

For he wounds, but he binds up;

he strikes, but his hands heal.” (Job 5:17-18)

This “encouragement” is being given to a man who just lost everything he owned, his health and his family! Yet, they insist, if Job would simply acknowledge that he is being justly disciplined he would get his protection and blessing back from God:

“[God] will deliver you from six troubles;

in seven no harm shall touch you.

In famine he will redeem you from death,

and in war from the power of the sword. ” (Job 5:19-20)

“At destruction and famine you shall laugh,

and shall not fear the wild animals of the earth.

You shall know that your tent is safe,

you shall inspect your fold and miss nothing.

You shall know that your descendants will be many,

and your offspring like the grass of the earth.

You shall come to your grave in ripe old age,

as a shock of grain comes up to the threshing floor in its season.

See, we have searched this out; it is true.

Hear, and know it for yourself.” (Job 5:22,24-27)

As cliché assurances often are, these words are self-serving and wounding. Promising a father who just lost all his children (Job 1:18-19) that if he will only get right with God his “tent” will be safe, his children will not be missing and his offspring will be like “the grass of the earth” is not just hollow: it is positively cruel. It is what Job’s friends want to believe, for they want assurance that what happened to Job can’t happen to them. But their wish-based theology is out of sync with reality and completely unhelpful to their suffering friend.

One of the central points of this profound book is to expose the shallowness of this popular theology. When God shows up to reveal the truth in several speeches at the end of the book (chs 37-41), he does not concede that what happened to Job had anything to do with disciplining or punishment. Indeed, God angrily rebukes Job’s friends for speaking erroneously about God (Job 42:7).

This is not to say that everything Job’s friends say about God is incorrect. This book is far too subtle to paint everything in either-or terms. It artfully paints a thoroughly ambiguous picture of the cosmos where those who are basically in the wrong sometimes speak right, and those whose hearts are basically right (Job) nevertheless speak many untruths, as we shall see (see Job 42:7). Yet the central point of the book’s portrayal of the friends’ “wisdom” to Job is that they speak out of massive ignorance.

Did Yahweh Bring About Job’s Trouble?

The theology of Job’s friends isn’t the only theology this book aims at correcting. Though it is often missed, this book also is intent on refuting Job’s theology. Against his friends, Job insists that he is not more blameworthy than they or any other human being. But since he shares his friends blueprint assumption that God is behind all that has happened to him, the only alternative conclusion available to him is that God is in fact arbitrary. When Yahweh appears at the end of this book, he no more agrees with Job’s theology than he agrees with the theology of his friends (Job 38-42).

One verse toward the end of this book has caused many to miss the point that this work intends to refute Job’s theology as well as that of his friends. When Yahweh is done speaking, the author notes that his friends consoled him for “the trouble (rah) the Lord had brought on him” (Job 42:11, NIV). Several considerations should prevent us from concluding that this verse implies that Job was correct in seeing God as the cause of all his suffering.

First, while everyone else at the time the Old Testament was written believed that the world was fashioned and ruled by many conflicting gods, the Old Testament emphasizes that everything ultimately comes from one Creator God. To drive home this highly distinctive belief, Old Testament authors consistently emphasize God as the ultimate source of everything that happens in creation. Even the consequences of free decisions are in a sense brought about by the Creator, in their view, for he alone created the people (or angels) who make their own decisions.

More specifically, Yahweh is depicted in terms of an ancient Near Eastern monarch who takes responsibility for what his delegates do, even if they do not carry out his own wishes in the process of doing it. An authority’s delegates are, in a sense, an extension of himself. In a context where the singularity of the cosmic monarch needs to be emphasized, such as we have in the Old Testament, the autonomy of the subordinate delegates is minimized and the Creator as the ultimate source of their authority is maximized. It is in this sense that everything humans and angels do is seen as coming from God.

But understood in an Ancient Near East context, this doesn’t entail that everything human or angelic agents do happens in accordance with God’s will, or that God is himself morally responsible for what the agents he creates choose to do. The heavenly and human agents Yahweh creates are the originators of their own free decisions and are morally responsible for these decisions. Yahweh is the ultimate source of their freedom, and he takes responsibility for the cosmos as a whole. But the agents themselves decide how they will use this God-given freedom. Hence, in this context, to say that something came from Yahweh, via another agent, is not to say that this thing was part of Yahweh’s own plan, that he directly brought it about, or that he in any sense wills it (though as the Creator he wills and brings about the possibility of evil deeds by creating agents free).

Second, and closely related to this, Job 42:11 needs to be interpreted in light of the prologue which clearly shows that it was the satan, not God, who afflicted Job. True, God entered into the wager with the satan and allowed him to afflict Job in order to answer the satan’s assault on his integrity. In this sense he brought Job’s troubles on him. But he did not himself plan or cause these afflictions, as Job later alleges. Indeed, as we noted above, the prologue goes out of its way to emphasize the haphazard nature by which Job’s life was turned upside down. The satan , who wanders about on his own while causing mischief (which Yahweh has to protect people from, Job 1:10), just happens to show up at a heavenly council meeting. What happened to Job was certainly not part of Yahweh’s perfect plan for his life!

Third, and even more importantly, we need to interpret this verse in the light of Jesus’ ministry, for Jesus is the central place where God’s character and will are revealed. In Jesus’ ministry, people who suffered the sort of afflictions Job suffered were diagnosed as being the direct or indirect victims of Satan’s warfare against God. God’s will was revealed not in the afflictions Jesus encountered, but in his loving and powerful response to these afflictions.

Along the same lines, Christ’s incarnation, death and resurrection reveal that though God is not culpable for the evil in the world, he nevertheless takes responsibility for the evil in the world. And in taking responsibility for it, he overcomes it. On the cross God suffers at the hands of evil. And in this suffering, and through his resurrection, he in principle destroys evil. Through the cross and resurrection, God unequivocally displays his loving character and establishes his loving purpose for the world, despite its evil resistance. He thereby demonstrates that evil is not something he wills into existence: it is something he wills out of existence.

Fourth, the most decisive indicator that the author of this book intends to refute Job’s theology is that Yahweh never acknowledges that he was the one behind Job’s suffering in his climatic speeches at the end of this book. As we shall see, he rather appeals to factors in creation to explain to Job why he can’t understand his suffering.

Job gets the point, for when God is done talking he repents (42:6) and confesses, “I have uttered what I did not understand” (Job 42:3). However we interpret Job 42:11, therefore, it can’t be taken to endorse a theology Yahweh refutes and Job repents of.

Job’s Misguided Theology.

A final clear indication that the author does not intend to endorse Job’s theology is that many of the things Job says throughout this work are things no one would recommend that people embrace – though they are, in fact, logical consequences of the assumption that God is behind Job’s suffering. For example, throughout the narrative Job depicts God as a cruel tyrant who controls everything in an arbitrary fashion. “When disaster brings sudden death,” Job exclaims,

“[God] mocks at the calamity of the

innocent.

The earth is given into the hand of the

wicked;

He covers the eyes of its judges –

If it is not he, who then is it?” (Job 9:23-24, cf. 21:17-26, 30-32; 24:1-12)

God laughs at the misfortunes of the innocent and causes judges to judge unjustly! Can anyone imagine a biblical author endorsing this perspective? Of course not. But it gets worse:

“Why are times not kept by the

Almighty?

And why do those who know him

never see his days?” (Job 24:1)

“What is the Almighty, that we should serve him?

And what profit do we get if we pray to him?” (Job 21:15)

“From the city the dying groan,

And the throat of the wounded cries

for help;

Yet God pays no attention to their

prayer.” (Job 24:12)

The victims of injustice – which God himself is bringing about – cry for help, but God pays no attention to their prayers. Are we to believe that this is the view the author is recommending, in contrast to the theology of Job’s friends?

Yet Job’s depiction of God is even harsher when he considers the injustice of his own state. For example, Job cries out to the Lord,

“Your hands fashioned and made me;

And now you turn and destroy me” (10:8).

“Bold as a lion you hunt me;

And repeat your exploits against me…

Let me alone; that I might find a little

comfort” (10:9, 20).

“You have turned cruel to me;

and with the might of your hand you

persecute me” (30:21).

And to his friends Job testifies,

“…God has worn me out;

he has made desolate all my

company.

And he has shrivelled me up…

He has torn me in his wrath, and

hated me;

He has gnashed his teeth at me;

my adversary sharpens his eyes

against me” (16:7-9, cf. 11-17).

“With violence he seizes my garment;

He grasps me by the collar of my

tunic…” (30:18).

Are we to believe that these are theological insights the author of this work is recommending to his readers? Are we to view God as our “adversary” instead of our “advocate” (cf. Jn 14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7; I Jn 2:1)? Are we to believe that our comfort is to be found when God leaves us alone (Job 10:20) rather than when he is with us? Doesn’t the God Job describes in these passages sound much more like “a roaring lion… looking for someone to devour” – in other words, “your adversary the devil” (I Pet 5:8)? Of course it does, which is why Job later confesses “I have uttered what I did not understand” (Job 42:3) and proclaims, “I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes” (Job 42:6).

In times of tragedy, people often quote Job’s words “the Lord gave and the Lord has taken away” (Job 1:21) when someone has lost something or someone precious to them. The irony is that, though they are spoken from an honest and upright heart, these words are part and parcel of a theology Job repents of. Though Job initially “did not sin or charge God with wrong-doing” (Job 1:22), this theology ultimately led Job to complete despair. Before long Job would work out with ruthless clarity the implications of what he believed, as we saw above.

When the despairing Job complained, “Your hands fashioned and made me; And now you turn and destroy me” (10:8), was he not articulating, in less pious terms, the same view of God when he earlier said, “the Lord gave and the Lord has taken away”? Though his willingness to submit changed to rage as his despair deepened, his view of God remained the same. As we have seen, for Job, the God who arbitrarily gives and takes away is a capricious destroyer, a vicious predator, an adversary of humanity, the source of all suffering and injustice, a mocker of the innocent, and a God who doesn’t heed the prayers of those in need.

This is definitely not the view of God the author of this inspired book is commending to his readers. But it is the view of Job, and is completely consistent with the assumption, shared by his friends, that God is behind each and every adversity in life.

The Straightness of Job’s Heart.

When God shows up to set the record straight, providing us with a three chapter climax of this book, he corrects the thinking of both Job and his friends (chs 38-41). Job passed his test not because his theology was correct, but because he did not reject God even when his theology told him he should. Despite his theological misconceptions, and despite his impious ranting throughout the narrative, Job’s heart remained honest with God. His friends’ theology usually sounded much more pious, but their hearts were actually farther from God than was Job’s. In the words of John Gibson,

“Of course God did not approve of everything that his proud and litigious servant had said about him (his speeches from the whirlwind have made that abundantly clear), but he infinitely preferred Job’s attacks on him to the friends’ defense of him” (1)

Job spoke straight (kûn) about God, from the heart, while his friends spoke in self-serving ways (Job 42:7). Not only this, but Job worked out his theology with ruthless consistency. If God were in fact the all-controlling deity Job assumed him to be, then the terrible conclusions he drew about God were “right.” Yet, despite this conception of God, Job did not reject him in his heart. Against the charge of the satan, he thereby proved that people can worship God of their own free will, just because he is God, and not because there’s something in it for them when they do so.

Vastness and Complexity of Creation.

Still, God wanted to correct Job’s theology as much as that of his friends. Hence, in the concluding speeches, God no more acknowledges Job’s perspective than he does the friends’ perspective. Rather, he refutes both perspectives by alluding to two facts: human ignorance about the vastness and complexity of the cosmos; and human ignorance about the enormity of the powers of chaos that God must contend with.

To highlight the first fact, the Lord asks Job, “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?” (Job 38:2). “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?” (Job 38:4). And he continues:

.

“Who determined its measurements—surely you know!

Or who stretched the line upon it?

On what were its bases sunk,

or who laid its cornerstone

when the morning stars sang together

and all the heavenly beings shouted for joy?” (Job 38:5-7).

“Have you comprehended the expanse of the earth?

Declare, if you know all this” (Job 38:16-18).

“What is the way to the place where the light is distributed,

or where the east wind is scattered upon the earth”? (Job 38:24).

“Do you know the ordinances of the heavens?

Can you establish their rule on the earth?” (Job 38:33).

The point of these questions is to expose the massive ignorance of Job and his friends. The Lord is putting all of them in their place to demonstrate how arrogant it is for Job’s friends to accuse him or for Job to accuse God. Since we know so little about the vastness, complexity, and ordinances of creation, we are in no position to accuse anyone. But note, the ignorance the Lord highlights in this passage is an ignorance about creation. Job’s friends accuse Job, and Job accuses God, because they fail to a humbly acknowledge the complexity of the world God has created and their vast ignorance about it.

Decision Making and Chaos Theory

A recent development in science helps illustrate the point God is making to Job, for it highlights the interconnected complexity of life and the impossibility of our ever exhaustively comprehending it. It is called chaos theory.

Put in simplest terms, it has recently been demonstrated that the slightest variation in a sufficiently complex process at one point may cause remarkable variations in that process at another point. The flap of a butterfly wing in one part of the globe can, under the right conditions, be the decisive variable that brings about a hurricane in another part of the globe several months later. (Hence this has been called “the butterfly effect.”) To exhaustively explain why a hurricane (or any weather pattern for that matter) occurs when and where it does, therefore, we’d have to know every detail about the past history of the earth – including every flap of every butterfly wing that ever existed! We of course cannot ever approximate this kind of knowledge, which is why weather forecasting will always involve a significant degree of guesswork.

By analogy, this insight may be applied to free decisions. Because love requires choice, humans and angels have the power to affect others for better or worse. Indeed, every decision we make affects other agents in some measure. Sometimes the short-term effects of our choices are apparent, as in the way the decisions of parents immediately affect their children or the way decisions of leaders immediately affect their subjects. The long-term effects of our decisions are never obvious, however. They are like ripples created by a rock thrown into a pond. They endure long after the initial splash, and they interact with other ripples (consequences of other decisions) in ways we could never have anticipated. And in certain circumstances, they may have a “butterfly effect.” They may be the decisive variable that produces significant changes in the pond.

We might think of the over-all state of the cosmos at any given moment as the total pattern of ripples of a constant stream of rocks thrown into a pond. Each ripple interacts with other ripples, creating interference patterns. Every event and every decision that takes place in history is such an interference pattern. They are the result of multitudes of decisions intersecting with one another in various ways. And once each event or decision occurs, they then contribute to all subsequent interference patterns.

Each individual influences the whole by how they use their morally responsible “say-so,” creating ripples that affect other agents. And as the originators and ultimate explanation for their own decisions, they assume primary responsible for the ripples they create. Yet each individual is also influenced by the whole. Decisions others have made have affected their life, and these people were themselves affected by decisions others made. In this sense every event and every decision is an “interference pattern” of converging ripples extending back to Adam, and each decision we make influences the over-all interference pattern that affects subsequent individuals.

From this it should be clear that to explain in any exhaustive sense why any particular event took place just the way it did, we would have to know the entire history of the universe. Had any agent, angelic or human, made any decision different than it did, the world would be a slightly different – or perhaps significantly different – place. But we, of course, can never know more than an infinitesimally small fraction of these previous decisions, let alone why these agents chose the way they did. Add to this our massive ignorance of most natural events in history — which also create their own “ripples” — combined with our ignorance of foundational physical and spiritual laws that are operative in the cosmos, and we begin to see why we invariably experience life as mostly ambiguous and highly arbitrary. We are the heir to an incomprehensibly vast array of human, angelic, and natural “ripples” throughout history about which we know next to nothing but which nevertheless significantly affect our life.

Using a language Job could understand, this was essentially the point God was making in his first speech. We finite humans have no means of knowing the innumerable variables that would explain why things happen the precise way they happen. Whether we are speaking of human decisions, angelic decisions, or the flap of butterfly wings, the creation is too vast and complex for us to get our minds around. Yet every detail affects the course of things in at least a small way. Hence we experience life as largely arbitrary.

In the end, the question, “Why me?” — or “Why Job?” — is unanswerable. It is a mystery. But the point of the book of the Job — and a lesson we can appropriate from chaos theory – is that this is not a mystery about God’s will or character. It is a mystery surrounding the vastness and complexity of creation. We experience life as arbitrary simply because we are finite. And when we try to arrogantly deny this finitude by ignoring all we do not know about creation, we end up either indicting people (as Job’s friends did) or indicting God (as Job did). What we learn from this profound book is that the reason why Job – as opposed to someone else – suffered as he did had nothing to do with his sinful character or God’s arbitrary character. It rather had to do with a haphazard confrontation in the heavenly realm between God and an adversary that no one in the context of the narrative ever knew anything about.

When all is said and done, the mystery of why any particular misfortune befalls one person rather than another is no different than the mystery of why any particular event happens the way it does. Every particular thing we think we understand in creation is engulfed in an infinite sea of mystery we can’t understand. The mystery of the particularity of evil is simply one manifestation of the mystery of every particular thing.

The War That Engulfs Creation.

The second fact God alludes to in his correction of Job and his friends concerns the warfare that engulfs the creation. Ancient Near Eastern people depicted cosmic evil either as hostile waters that encircled and threatened to destroy the earth, or as cosmic creatures (identified as “Behemoth” in ch. 40 and “Leviathan” in ch. 41) who threatened to destroy the world. This was their way of thinking about demonic “principalities and powers,” and it is found throughout the Bible (e.g. Job 3:8, 9:13; 26:12; Psl 74:14; Psl 87:4, 89:10; Isa 27:1; 51:9). In order to make his point to Job, in a language Job could understand, Yahweh reminds him of his battle with both the raging sea and the cosmic monsters.

Regarding the cosmic sea the Lord says,

“…who shut in the sea with doors

when it burst out from the womb…

and prescribed bounds for it,

and set bars and doors,

and said, “Thus far shall you come, and no farther,

and here shall your proud waves be stopped?” (38:8, 10–11).

Yahweh is reminding Job of the proud and hostile sea which, all Ancient Near Eastern people believed, must be kept at bay if the order of the world is to preserved. Until Job thinks he can do a better job at this that God, he should be reticent to follow the satan’s lead and challenge God’s character and ability in running the cosmos.

Concerning Leviathan, the Lord asks Job, “Can you draw out Levia¬than with a fishhook, or press down its tongue with a cord?” (41:1). Only the Lord can contend with this malevolent creature (though even he needs a sword! [40:19]), for this cosmic beast is indeed ferocious:

“Its sneezes flash forth light,

and its eyes are like the eyelids of the dawn.

From its mouth go flaming torches;

sparks of fire leap out.

Out of its nostrils comes smoke,

as from a boiling pot and burning rushes.

Its breath kindles coals,

and a flame comes out of its mouth…

It counts iron as straw,

and bronze as rotten wood…” (41:18–21, 27).

This cosmic beast fears nothing (41:33). It cannot be captured or domesticated (41:1–8). Even “the gods” are “overwhelmed at the sight of it” (41:9, 25). And no one “under heaven” can “confront it and be safe” (41:11). Yahweh emphasizes the ferociousness of this beast not to call into question his own ability to handle it, but to stress to Job that this foe is indeed formidable. The battle Yahweh is engaged in is not a charade.

By reminding Job of the cosmic forces he must contend with, God again exposes the presumptuousness of the simplistic theologies of both Job and his friends. Neither considered the warfare that engulfs creation. Both simply assumed that things unfold the way Yahweh wants them to. Yahweh’s appeal to the battle he’s involved in alters these theologies considerably. It means that not everything happens exactly as Yahweh would wish. He himself must battle forces of chaos.

Fredrik Lindstöm, an eminent Old Testament scholar, sums up the matter well when he writes:

“[Yahweh] in fact partially admits to Job that there are parts of Creation which are indeed chaotic; here we catch sight of an understanding of the world in which evil… neither comes directly from God, as Job maintains, nor can it be accommodated to a world order in which it is ultimately related to human behavior, as Job’s friends claim.” (2)

And again,

“Job explicitly held [Yahweh] responsible for all the evil of existence, so [Yahweh] rebuts this charge by pointing to his own continuous combat with evil as manifested in these chaos creatures.” (3)

The cosmos is far more complex and combatant than either Job or his friends had assumed.

Another eminent Old Testament scholar, John Gibson, expresses the point even more forcefully. He notes that “[C]hapters 40 and 41 do not mention an open victory of God over Behemoth and Leviathan, but simply describe them as they are in their full horror and savagery.” From this he concludes that the central point of these chapters is to draw attention

“…to the Herculean task God faces in controlling these fierce creatures of his in the here and now. They are in fact set forth as worthy opponents of their Creator. They are quite beyond the ability of men to take on and bring to book. On the contrary, they treat men with scorn and derision, delighting to tease and humiliate and terrorize them….even God has to watch for them and handle them with kid gloves. It takes all his ‘craft and power’ to keep them in subjection and prevent them from bringing to naught all that he has achieved…. It is of this divine risk as well as of the divine grace and power that Job is… being given an intimation in Yahweh’s second speech: of the terrible reality of evil and (as Job himself was now only too well aware) of the dangers it presents to men…”(4).

The point of Yahweh’s second speech — the foundation of which was laid in the prologue, as we have seen — is that things go on “behind the scenes” that are not part of God’s plan, are not directly under God’s control and in fact that resist God’s providential control, but which nevertheless affect human lives. We know next to nothing and can do next to nothing about these happenings. Hence we experience life as an arbitrary flux of fortune and misfortune.

The fact that neither Job nor his friends are ever told about the satan who began the whole mess reinforces this point. After the prologue the satan is not mentioned again. The main characters of this epic poem never learn what the reader knew all along. And this is precisely the point of the book. We don’t know and can’t know why particular harmful events unfold exactly as they do. What we can know, however, is why we can’t know. And the reason we can’t know is not because God’s plan or character is mysterious, but because we are finite humans who exist in an incomprehensibly vast creation that is afflicted by forces of chaos. The mystery of the particularity of evil, which is no different than the mystery of the particularity of everything, is located in the mystery of creation, not the mystery of God. And given this mystery, we must refrain either from blaming each other, or blaming God, when misfortunes arise. Rather, following the example of Jesus, we must simply ask, What can we do in response to the evil we encounter?

Western Christians rarely take seriously the reality of the spirit world as a variable that affects their lives. We ordinarily assume that God’s will and human faith are the only two relevant variables that decide what comes to pass. So, for example, if we pray for something and it doesn’t come to pass, Christians typically conclude that it must not have been God’s will or that the person praying lacked faith, didn’t pray hard enough, or some such issue. The book of Job, the ministry of Jesus, and the Bible in general suggest that such formulaic thinking misses the complexity of the real world and is dangerous for just this reason.

A Delay in Daniel’s Prayer

One of the most intriguing and graphic illustrations of the significance of the spirit world in understanding what comes to pass is found in the book of Daniel. For three weeks Daniel fasted and prayed to hear from God, with no answer (Dan 10:3). Finally, an angel appeared to him and said,

“Do not fear, Daniel, for from the first day that you set your mind to gain understanding and to humble yourself before your God, your words have been heard, and I have come because of your words. But the prince of the kingdom of Persia opposed me twenty-one days. So Michael, one of the chief princes, came to help me, and I left him there with the prince of the kingdom of Persia” (Dan. 10:12-13).

The delay in answering Daniel’s prayer had nothing to do with God’s will or Daniel’s lack of faith or piety. It was rather due to the interference of a demonic spirit called “the prince of the kingdom of Persia.” As we have seen, because God’s purpose in creation is love, he wants to carry out his will through agents who choose to love and obey him. Hence he usually works through mediators, both on a physical and spiritual level. And what happens to these mediators affects the way God’s will is carried out through them. When they align themselves with God’s purposes, things go smoothly. But when they set themselves in opposition to God’s will, such as this territorial spirit had done, God’s will is disrupted. Only when the angel Michael could help him out was this angel who was dispatched to answer Daniel’s prayer freed to do so.

Not only this, but after arriving the angel tells Daniel why he has to leave quickly.

“Now I must return to fight against the prince of Persia, and when I am through with him, the prince of Greece will come…There is no one with me who contends against these princes except Michael, your prince” (Dan. 10:20-21).

It seems that Michael was now in need of his help in battling the spiritual powers that opposed God. Perhaps there were no other angels on God’s side available to aid him. People often assume that God has an unlimited number of angels available to him. But Scripture suggests that the nature of things in the spiritual realm is not that different from the nature of things in our physical realm. Because God has chosen to work through physical and spiritual mediators who are finite in number and strength, the way battles progress is influenced by the number and strength of agents fighting for or against his purposes.

Through this episode we gain a rare glimpse of the sorts of things that go on behind the scenes that affect our lives. Had the angel not revealed this information to Daniel, Daniel would never have known why it took twenty-one days for his prayer to be answered. It would have seemed totally arbitrary. No doubt some would have followed Job’s lead and said, “It must not be God’s will” or “God’s timing is the best timing.” Others would have followed his friends lead and concluded, “Daniel must lack faith or must not be righteous.”

In point of fact, the delay had nothing to do with either of these variables. It rather had to do with agents in the spiritual realm who possess “say-so” and who use it to either further or resist Gods’ purposes. Like humans, angels create ripples that create interference patterns with other ripples, for better or for worse. Yet we can know even less about angelic ripples than we can about human ripples.

Conclusion

Most of us do not like ambiguity. Life is generally easier if we convince ourselves that everything is clear and simple. This, I believe, is part of our legacy of eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen 3:1-7). In our fallen delusion, we feel it our right, and within our capacity, to declare unambiguously who and what is “good” and who and what is “evil.” We are not omniscient, but having eaten from the forbidden tree, we have a fallen misguided impulse to judge matters as though we were. We have difficulty accepting our finitude and the massive ignorance and ambiguity that necessarily attaches to it.

In point of fact, however, the creation could only be experienced by finite beings such as ourselves as unfathomably complex and therefore mostly ambiguous. We have no means of ascertaining more than a minute fraction of the variables that factor into each and every event within this unfathomably complex creation. This is not because we are fallen: it is simply because we are finite. This is why our original job description – a job description God is yet calling on us to fulfill – involves very little knowing but a great deal of loving. Our limited domain of responsibility is primarily to love God and others as we are ourselves filled with God’s love. Hence the Bible repeatedly calls on us to love and refrain from judgment (Mt 7:1-5; Rom 2:1-5; Jame 4:11-12).

Because of our fallen addiction to the forbidden tree, however, we want to know and judge. If our finite knowledge can’t adjust to the complexity of reality, we simply try to readjust the complexity of reality to our finite capacity to know. Hence we bracket off the complexity of reality and act like things are simple enough for us to understand.

This is why many of us are compulsively inclined to judge people on the basis of the surface behavior we see, bracketing off the vast complexity of variables that affect and perhaps explain this perceived behavior. Though the Bible expressly forbids it, pretending like we can know and judge a person’s heart gives us a sense of ethical superiority and personal security. And this is also why we are inclined toward simplistic, formulaic theologies . Like Job’s friends, and like Job himself, we feel secure and justified when we bracket off the complexity and ambiguity of reality and convince ourselves that the world unfolds according to a divine blueprint. We assume that everything can be explained simply by appealing to God’s will and/or the will of people.

Yet, this theology works only so long as we can in fact bracket off reality. But when reality in all its unfathomable complexity and war torn horror encroaches in on us, our theology suffers and victims suffer. When we compromise what we do know because we forget what we don’t know — when we make the mystery of evil a mystery about God rather than creation — we tarnish God’s character and indict victims of war. As depicted in the book of Job, some blame God, others blame people. But, as the book of Job teaches us, both responses are fundamentally mistaken.

A healthier perspective, and a perspective which both honors God’s character as it is revealed in Christ and refrains from indicting people, is one that acknowledges the ambiguity and the warfare up front. We must with confidence anchor ourselves in what we can know – that God looks like Jesus – and simply confess ignorance about everything else.

If we are going to blame anyone, the book of Job and the ministry of Jesus would have it be Leviathan, Behemoth, hostile cosmic waters or (what comes to the same thing) the devil. Though we can’t know the “why” of any particular instance of suffering, we can and must know that our whole environment is under siege by forces that hate God and hate all that is good. We are by our own rebellion caught in the crossfire of a cosmic war, and we suffer accordingly.

End Notes

(1) J.C.L. Gibson, “On Evil in the Book of Job,” in Ascribe to the Lord: Biblical and Other Studies in Memory of Peter C. Craigie, eds. L. Eslinger & G. Taylor, JSOT Sup. 67 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1988), 265.

(2) F. Lindstöm, God and the Origin of Evil: A Contextual Analysis of Alleged Monistic Evidence in the Old Testament, trans. F. H. Cryer (Lund: Gleerup, 1983), 154.

(3) Lindström, God and the Origen of Evil, 156.

(4) J. C. L. Gibson, “On Evil in the Book of Job,” in Ascribe to the Lord: Biblical and Other Studies in Memory of Peter C. Craigie, eds. L. Eslinger & G. Taylor, JSOT Sup. 67 (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1988), p. 412. See also idem., Job, pp. 225-56, and idem., Language and Imagery in the Old Testament (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1998), 99-103. Other scholars who share this general perspective are, O. Keel, Jahwes Entgegung an Ijob; FRLANT 121 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1978); J. Day, God’s Conflict with the Dragon and the Sea (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 62-87, and T. Mettinger, “The God of Job: Avenger, Tyrant, or Victor?,” in The Voice from the Whirlwind: Interpreting the Book of Job, eds. L. G. Perdue and W. C. Gilpin (Nashville: Abingdon, 1992), 39-49.

_______ _______

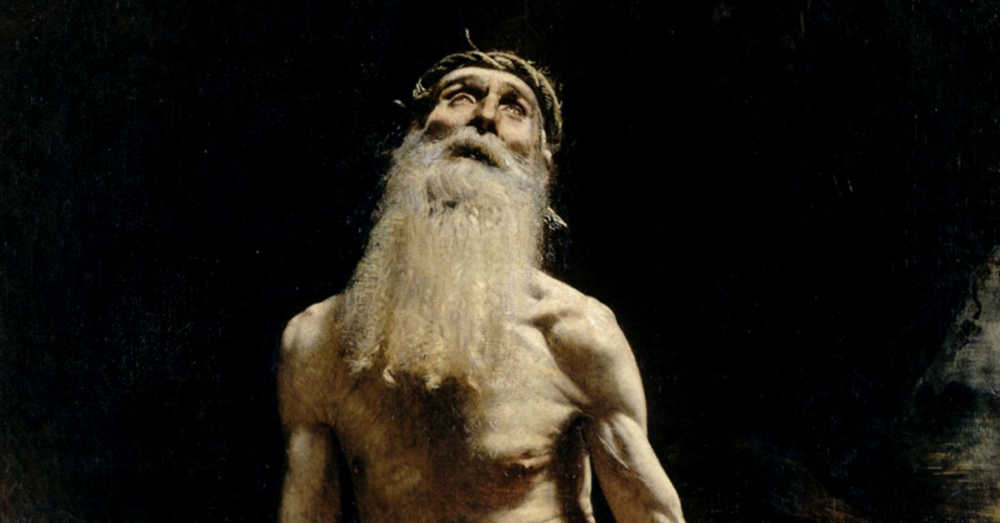

Art: “Job”

By: Leon Bonnat

Category: Essays

Tags: Apologetics, Bible, Essay, Old Testament, Problem of Evil

Topics: The Problem of Evil

Related Reading

Imaging God Rightly: God’s Self-Portrait, Part 3

In the previous two blogs I noted that the vision of God in our minds is the single most important vision in our lives, for it completely determines whether we’ll have a relationship with God and what kind of relationship this will be. A. W. Tozer once wrote, “What comes into our minds when we…

Is the Bible History?

Even though I argued for interpreting the final form of the biblical canon as opposed to using the history behind the text in my post yesterday, I am not endorsing the radical post-modern view that biblical texts possess “semantic autonomy” and thus lack any historical referentiality. While I have no problem whatsoever accepting that God used folklore and myth…

How To Talk about Theology

Social media is full of theological debate. Theological arguments that formerly took months or even years to get in print, now only takes the time to write a post or 140 characters and click “publish.” Social media is great in that it makes space for all of our voices. However, it also seems to elevate…

What’s the Purpose of the Old Testament Law?

Whereas the old covenant was rooted in the law, the new covenant is rooted in simple faith, such as Abraham had. Whereas the old covenant was forged with one particular nation, the new covenant is available to all who are willing to accept it, regardless of their ethnicity and nationality. Whereas forgiveness of sins within…

When the Bible has Errors

In the previous post, we dealt with the question of why we are able to trust Scripture. But we need to explore this further because if you read the Bible carefully, you will find parts that look erroneous. Some aspects of the Bible don’t line up with what we know from history and science. Let’s…

Past Sermon Series: Faith & Doubt

Faith is sometimes understood as the lack of doubt. As a result, doubt can be seen as the enemy of faith. But Biblical faith can withstand doubt and even be strengthened by it. God wants His people to wrestle with Him on the things that matter in their lives. We must not be afraid of struggling with deep…