We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

How People Misunderstand Open Theism

Open theism holds that, because agents are free, the future includes possibilities (what agents may and may not choose to do). Since God’s knowledge is perfect, open theists hold that God knows the future partly as a realm of possibilities. This view contrasts with classical theism that has usually held that God knows the future exclusively as a domain of settled facts. There are no “maybes” for God.

The debate is not about the scope and perfection of Gods’ knowledge, for both open theists and classical theists affirm God’s omniscience. God always knows everything. The debate, rather, is about the content of the reality God perfectly knows. It comes down to the question of whether or not possibilities are real.

I’m always puzzled as to why many defenders of the classical theism spin the debate with open theists as a disagreement over the perfection of God’s knowledge. For example, they publish books with titles like How Much Does God Know? (Steven Roy) and What Does God Know and When Does He Know It? (Millard Erickson). Since open theists believe God always knows everything, why do they continue to argue as if we don’t?

Part of the explanation, of course, may be simple propaganda. My sense is that, while spinning the debate as about God’s knowledge rather than the nature of reality certainly is advantageous for the purpose of propaganda, the critics who argue this way also seem to sincerely believe what they’re saying. How can this be?

While researching some ancient philosophers who influenced theologians like Augustine and Boethius, I uncovered something that may help explain this curious phenomenon. Let me briefly explain.

First, Plato argued that we see not by light entering our eyes (as we now know is the case) but by light proceeding out of our eyes (Timaeus 45b). For Plato, seeing is an active, not a passive, process. Since knowledge was considered to be a kind of seeing, Plato also construed knowing as acting on something rather than being acted upon (Sophist 248-49). I’ve discovered that this mistaken view of seeing and knowing is picked up and defended by a host of Hellenistic philosophers.

Second, several Neoplatonistic philosophers (Iamblichus, Proclus and Ammonius) used this theory of eyesight and knowing to explain how the gods can foreknow future free actions. They argued that the nature of divine knowledge is determined not by what is known but by the nature of the knower. Since they assumed the gods were absolutely unchanging, they concluded that the gods knew things in an absolutely unchanging manner, despite the fact that the reality the gods know is in fact perpetually changing. This allowed them to affirm that the future partly consisted of indefinite (aoristos) truths (viz. open possibilities) while nevertheless insisting that the gods knew the future in an exhaustively definite, unchanging way.

The view is, I’m convinced, completely incoherent. But one can understand how these philosophers arrived at it in light of their mistaken assumptions about seeing and knowing as wholly active processes. What the gods see when they look at the future conforms to the unchanging nature of the gods rather than the changing nature of the future they see. Through the influence of Augustine and especially Boethius (who explicitly espoused the ancient view of seeing and knowing and repeated some of the Neoplatonic arguments), this way of “reconciling” foreknowledge and free will quickly established itself as the dominant view in the Christian tradition.

And it is, I suspect, this same mistaken tradition that at least in part explains why many contemporary defenders of classical theism today instinctively assume the debate over open theism is a debate about the nature and perfection of God’s knowledge rather than a debate about the nature of the future.

Once we abandon the ancient view of seeing and knowing as active processes, it becomes clear that God’s knowledge is perfect if, and only if, it perfectly conforms to the nature of what is known. So if possibilities are real, then God’s knowledge is perfect if, and only if, God knows them as possibilities. Contrary to what critics of open theism claim, open theists affirm that God always knows everything perfectly. It’s just that we have reason to believe a partly open future is part of what God perfectly knows.

Image by SortOfNatural via Flickr

Category: General

Tags: Calvinism, Divine Foreknowledge, Free Will, freedom, Future, Open Future, Open Theism

Topics: Free Will and the Future, Open Theism What it is and is not

Related Reading

The Lego Movie & Free Will

Last week Greg tweeted about two movies that have themes related to human free-will and God’s control of the world. They were: @greg_boyd: Does God want a permanently frozen “perfect” world or an open-ended world filled with wildly imaginative people? Watch “The Lego Movie”! @greg_boyd: Meantime, me & some peeps are going to watch (again!)…

God’s Moral Immutability

Classical theologians from the fourth and fifth centuries on were very concerned with protecting their understanding of the metaphysical attributes of God—like timelessness, immutability, impassibility—by assessing biblical portraits that conflicted with these attributes to be accommodations. However, once we resolve that all our thinking about God must be anchored in the cross, our primary concern…

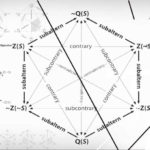

The Logical Hexagon Made Simple

by: Greg Boyd The Hexagaon in a Nutshell For those of you who don’t have the twenty to thirty minutes it will probably take to read this essay but who nevertheless would like to have some idea of what the Logical Hexagon is all about, here is my two sentence elevator speech: The Logical Hexagon…

Resisting Evil

The New Testament refers to Satan as the “god of this age” and the “ruler of the power of the air” (2 Cor 4:4; Eph.2:2). In the first century Jewish worldview, “air” referred to the domain of spiritual authority over the earth. The author, Paul, was thus saying that the spiritual environment of the earth…

Revelation 13:8 refers to “everyone whose names have not been written before the foundation of the world in the book of life.” How does that square with open theism?

Three possibilities exist in terms of reconciling Revelation 13:8 with open theism. 1) First, the “from the foundation of the world” clause can attach to either “everyone whose names have not been written” or to “the lamb that was slain.” For example, the TNIV translates this passage “All inhabitants of the earth will worship the…

What is the significance of Acts 27:10-44?

This is the passage deal with Paul’s ill-fated voyage to Italy as a prisoner. The ship ran into very bad weather and Paul announced, “Men, I can see that our voyage is going to be disastrous and bring great loss to ship and cargo, and to our own lives also” (vs. 10). As he reminded…