We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Part 2: Disarming Flood’s Case Against Biblical Infallibility

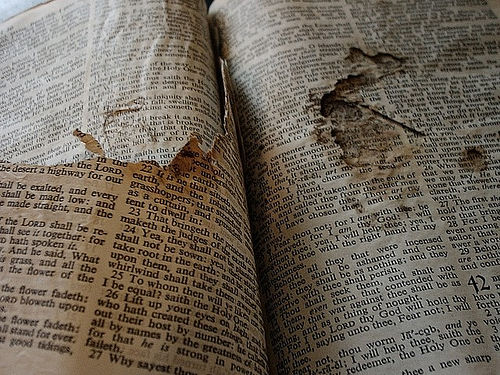

Image by humancarbine via Flickr

In this second part of my review of Disarming Scripture I will begin to address its strengths and weakness. [Click here for Part 1]

There is a great deal in Disarming Scripture that I appreciate. Perhaps the most significant thing is that Flood fully grasps, and effectively communicates, the truth that Jesus, Paul, and in varying degrees the entire New Testament, reveal a God who loves enemies and who is altogether non-violent (23-33). Indeed, he rightly notes that enemy love and non-retaliation constitutes “the core narrative of the New Testament” (123). It is for this reason that Flood feels the full gravity of the problem posed by the Old Testament’s violent portraits of God and violence-advocating narratives. And given the centrality of love and non-violence in the New Testament, I can only applaud Flood’s denouncement of Christian violence as the worst heresy imaginable (77).

Unfortunately, I don’t believe Flood’s treatment of the centrality of enemy-loving non-violence in the New Testament will persuade many dissenting scholars, for in the course of making his case, Flood failed to engage in the multitude of disputed exegetical and historical issues that surround the biblical material he cites. Indeed, while it is understandable given that this book was written for a popular audience, this is a vulnerability that characterizes a good deal of Disarming Scripture.

For example, I do not know if Flood was aware of this or not, but by claiming that Paul simply rejected violent material in the Old Testament because he employed a hermeneutic of love, Flood waded into a veritable minefield of contemporary scholarly debates surrounding Paul’s hermeneutic and its relationship to other interpretive strategies that were employed by Jews as well as pagans at the time. Disarming Scripture would have been academically stronger had Flood forged his position in dialogue with dissenting academics voices, but, of course, this also would have made his book less accessible to a lay audience.

Another feature of Disarming Scripture that I enthusiastically applaud is that Flood doesn’t try to minimize or excuse the violence that is held up as godly or that is attributed to Yahweh in the Old Testament. He boldly demonstrates that “[g]enocide, cannibalism, and rape are all attributed to God in the Old Testament” (5), and he forthrightly denounces these actions as evil. Not only this, but Flood shows how these violent portraits of God and of his people are dangerous, for they have been used by Christians throughout history to justify genocide and other barbaric forms of violence (10-4, 85). Flood correctly notes that when conservative Christian apologists condone these violent portraits, they are allowing them to continue to influence believers toward violence.

I also appreciate the fact that Flood contends that we cannot simply ignore this violent material. Flood argues against liberal Christians who cherry-pick their way through Scripture, acting as if the horrendous actions and attitudes that are sometimes attributed to God and his people in the Old Testament didn’t exist (13-8). For example, how often do we hear preachers and writers appeal to the Exodus narrative to proclaim that God is a liberator of oppressed people without acknowledging that this story was anything but a story of liberation for the Canaanites! While we may thankfully celebrate the profoundly beautiful aspects of the biblical narrative, Flood is right in arguing that we must also honestly wrestle with its “texts of terror” (105).

Having said this, I must admit that I am very concerned with the high theological price tag that Flood’s approach requires, for, as I noted in the first part of this review, it requires that we deny biblical infallibility. I understand and appreciate why Flood felt he had to move in this direction. And if we were forced to chose between compromising the revelation of God in Christ by embracing the surface meaning of the Old Testament’s violent portraits of God, on the one hand, or comprising the traditional view of Scripture, on the other, then I believe Flood made the right choice. I simply don’t believe these are our only two options, as I’ll argue in Part IV of this review.

Flood offers several arguments against the concept of biblical infallibility. First, he argues that this concept is not only mistaken, it is actually irrelevant, for “[e]ven if the Bible is infallible, we are not” (230). This is reflected in the fact that “there are so many conflicting interpretations of the Bible.” From this Flood concludes that, “if those who affirm that the Bible is infallible in what it teaches can’t agree on what exactly it is that the Bible in fact teaches…how then can we practically say that the Bible is our ‘supreme and final authority’ on these matters” (231-2, cf., 255)?

This doesn’t strike me as a particularly compelling argument, for Flood is conflating the interpretation of an authority with the stature of the authority. These are two very different things. To illustrate, the nine judges who comprise America’s Supreme Court are legally bound to esteem the Constitution as their supreme authority in deciding legally disputed cases. Yet, they hardly ever have full agreement on how to interpret and apply this supreme authority. And this simply demonstrates that the stature of an authority is not affected by disagreements about its interpretation. The same holds true for all of us who consider Scripture to be our infallible supreme authority.

In fact, not only do disagreements about an authority not render its supreme status moot, as Flood claims, but disagreements over the interpretation of an authority are only meaningful, and progress is only possible, when the stature of the authority in question is agreed upon. Imagine how chaotic and dysfunctional the Supreme Court would be if each judge was allowed to reject whatever aspects of the Constitution they disapproved of? It is only because these judges are legally bound to agree that the supreme authority of the Constitution is not up for dispute that they can have any hope of persuading one another of their various interpretations.

Throughout the Church tradition, Scripture has functioned very much like the Constitution functions in the Supreme Court. All hermeneutic and theological disputes were traditionally predicated on the assumption that the supreme authority and infallibility of the entire canon is not up for dispute. And, as we have seen in liberal theological circles over the last two centuries, cutting the tether with this tradition has the same effect on the theology of the Church as denying the supremacy of the Constitution would have for our Supreme Court.

Flood appeals to a second and “more substantial” criticism of the concept of biblical infallibility, but I’m afraid it suffers from the same confusion as his first. He writes:

[T]he problem is not simply that people cannot agree on what the Bible says, but that the Bible—when it is interpreted in an unquestioning way—inevitably leads to violence and abuse….[I]t is…an empirical historical fact that an unquestioning reading of the Bible has a long history of people endorsing things like slavery, child abuse, and genocide – all in the name of an ‘infallible” Bible (232-3).

It is of course true that there is a long history of Christians doing diabolic things “in the name of the ‘infallible’ Bible.” And I will even grant that this was due to Christians “interpreting the Bible in an unquestioning way.” But this violence was not because belief in an infallible Bible “inevitably leads to violence and abuse,” but because of the “unquestioning” and violent way certain Christians interpreted the infallible Bible. If the problem was the belief in biblical infallibility itself, how would Flood explain people like myself whose faith in the infallibility of Scripture leads them to unconditionally refrain from violence and to instead commit to loving enemies? It seems Flood has once again conflated the Bible’s infallible stature with the “unquestioning” violent way some interpret it.

This confusion unfortunately runs throughout Disarming Scripture. Flood regularly moves from talking about the need to question and/or reject interpretations of Scripture to talking about the need to question and/or reject passages of Scripture. To cite just one example, at one point Flood states that, “[n]ot only does Jesus reject these narratives (that justify violence), he attributes them to the way of the devil” (42, cf., 43-4). But immediately after this Flood notes that, “Jesus made a habit of questioning and rejecting how Scripture was read and applied (44).” Jesus questioned “hurtful interpretations of Scripture” (33). And for Jesus, according to Flood, any “reading that leads to harm rather than love is…a wrong reading” (45). But there is surely an important distinction to be made between questioning hurtful interpretations of Scripture and rejecting Scripture itself when one thinks it is hurtful.

Along the same lines, Flood at one point notes that “the focus…in Jesus and Paul is on interpreting the biblical text in such a way that it leads to love and compassion,” for “Scripture, when right, must lead to love” (69). So too, he argues that Paul had a “transformative hermeneutic” that sought to “redeem…rather than reject” violent passages (58). Yet, just after talking about Jesus’ and Paul’s focus on interpreting the Bible, Flood goes on to say, “we may not dare to cross out violent passages with our pens as Paul did” (69).

Now, it’s not clear to me why we dare not cross out violent passages since Flood believes “Jesus expects his disciples—expects you and me—to be…knowing what to embrace in the Bible and what to reject” (43). Nor is it clear to me how Flood can claim that Paul “redeemed” rather than rejected violent passages while also stating that Paul crossed out violent passages. Is there a distinction between “crossing out” and “rejecting” I’m not picking up on? But the more important confusion is that there is a world of difference between interpreting biblical texts in a way that “leads to love and compassion,” on the one hand, and crossing out texts because you think they can’t lead to love and compassion, on the other. Yet, Flood speaks as if they were at least overlapping endeavors. Given my conviction that a great deal hangs in the balance on distinguishing between Scripture and the interpretation of Scripture, I found this constant conflating of the two to be very frustrating.

In my estimation, it is this ambiguity more than anything else that required Flood to diminish the divine stature of Scripture in the process of arguing against violent ways of interpreting it. I completely agree that we must, in the light of Christ, reject violent interpretations of Scripture. But rather than denying the divine authority of a passage that is interpreted violently, I will later argue that we should feel compelled to continue to consider non-violent ways of interpreting the passage, precisely because it has divine authority. And I will argue that such interpretations open up for us when we read the Old Testament through the lens of the cross.

Having responded to Flood’s arguments against biblical infallibility, I will tomorrow turn to critique Flood’s revised understanding of the inspiration and authority of Scripture.

Category: General

Tags: Bible, Biblical Authority, Book Reviews, Derek Flood, Disarming Scripture, Jesus, OT Violence, Paul

Related Reading

When You Doubt the Bible

Kit via Compfight Many people enter into conversations with ReKnew and Greg’s writings because they have questions and doubts about the Bible which they do not feel they can ask within their current church tradition. When they arise, and they will, what do we do with them? How do we process them in a healthy…

A Dialogue with Derek Flood: Is the Bible Infallible?

I’m happy to see that Derek Flood has responded to my four part review of his book, Disarming Scripture. His response—and, I trust, this reply to his response—models how kingdom people can strongly disagree on issues without becoming acrimonious. And I am in full agreement with Derek that our shared conviction regarding the centrality of…

On Biblical Inerrancy

Matthew Kirkland via Compfight In this essay, Peter Enns explains his views on Biblical inerrancy and the complexities encountered as evangelicals attempt to define the term. From the essay: Speaking as a biblical scholar, inerrancy is a high-maintenance doctrine. It takes much energy to “hold on to” and produces much cognitive dissonance. I am hardly…

When God is Revealed

Whether we’re talking about our relationship with God or with other people, the quality of our relationships can never go beyond the level of trust the relating parties have in each other’s character. We cannot be rightly related to God, therefore, except insofar as we embrace a trustworthy picture of him. To the extent that…

Not the God You Were Expecting

Thomas Hawk via Compfight Micah J. Murray posted a reflection today titled The God Who Bleeds. In contrast to Mark Driscoll’s “Pride Fighter,” this God allowed himself to get beat up and killed while all his closest friends ran and hid and denied they even knew him. What kind of a God does this? The kind…

When the Bible Becomes an Idol

In John 5, we read about Jesus confronting some religious leaders saying, “You study the Scriptures diligently because you think that in them you have eternal life. These are the very Scriptures that testify about me, yet you refuse to come to me to have life” (John 5:39-40). These leaders thought they possessed life by…