We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

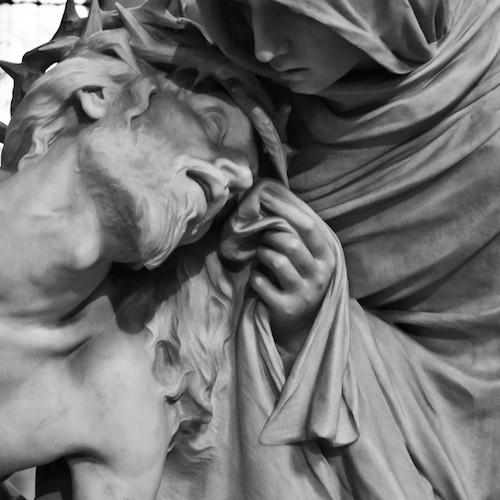

Final Thoughts on Copan’s Critique of Crucifixion of the Warrior God

I want to sincerely thank Paul Copan for his well-researched critique of Crucifixion of the Warrior God (CWG) that I’ve been responding to over the last several weeks. He exposed areas in my work that needed buttressing up and/or clarifying, and he has helped introduce my ideas into the theological and philosophical marketplace of concepts that need to be debated. I of course couldn’t respond to every detail of Copan’s critique, but I believe I’ve adequately responded to his major arguments. In any event, I thought it appropriate to wrap up this series by taking a step back and making two more general observations about Copan’s critique of my thesis.

First, most of Copan’s critique focused on my claim that the God who is supremely revealed in the crucified Christ is a God whose very essence is self-sacrificial, enemy-embracing, non-violent love. “God is love,” as John says, and he defines the kind of love God is, and the kind of love we are called to embody, by pointing us to the cross (I Jn 4:8; I Jn 3:16). Copan pushed back on this claim by citing passages in the NT that he believes directly or indirectly implicate God in violence.

Now, throughout this series I have argued that these passages do not in fact implicate God in violence, but there is a more general, and more important, point that needs to be made. Even if, for the sake of argument, I were to grant that certain NT passages implicate God in violence, this wouldn’t itself undermine my cruciform hermeneutic or the Cruciform Thesis I derive from it.

Here is why. The heart of my cruciform hermeneutic is the claim that all Scripture should be interpreted through the lens of the cross and with the assumption that all Scripture ultimately points to the cross. I spend four chapters and almost two hundred pages in Crucifixion of the Warrior God grounding this hermeneutical perspective in Scripture. Surprisingly enough, Copan didn’t offer a single argument against this claim or the material I site in support of it. Yet the case I made for the cruciform hermeneutic stands even if I were to grant that certain NT authors didn’t believe that God was altogether non-violent.

Were I to concede this perspective, I could simply apply the cruciform hermeneutic to the passages in which NT authors reflect this belief. That is, since it’s clear that NT authors didn’t grasp the full significance of what God did in the crucified Christ with equal clarity or speed, I could easily view NT passages that (allegedly) ascribe violence to God as further divine accommodations, along the lines of what God did with OT authors. In fact, I proposed this approach when I dealt with Paul’s unloving references to opponents.

But even if we were to set this strategy aside and personally accept that God is not altogether opposed to violence, this still would not undermine the cruciform hermeneutic. We would still need to grapple with the horrendously violent acts attributed to God in the OT. After all, it’s one thing to concede (for example) that God was willing to kill two adult liars and thieves (Acts 5:1-10), and quite another thing to accept that God commanded the Israelites to mercilessly slaughter multitudes of women, children and babies as a holy sacrifice to him. In short, even if we conceded that God sometimes resorts to the kinds of violence certain NT authors (allegedly) ascribe to him, we still would need to account for depictions of God commanding and engaging in the horrendous types of violence certain OT authors ascribe to God.

On top of this, we would still need to ask, “How do macabre portraits of God like this one point to the character of God revealed on the cross?” If Copan rejects my claim that horrendously violent depictions of God in the OT do this by reflecting a God who humbly stoops to bear the sin of his people, then it is incumbent upon Copan to demonstrate an alternative way in which these depictions point to the cross. If Copan instead wants to reject my claim that all Scripture is supposed to be interpreted as pointing to the cross, then his critique should have focused on the four chapters of material in which I defend this claim. But, as I said, this material goes unmentioned in his critique.

Second, another aspect of my work that went untouched by Copan’s critique is the case I make for the Cruciform Thesis throughout volume two. I offer over 700 pages of evidence and argumentation in this volume that confirms that God didn’t actually engage in the violence that OT authors ascribe to him and that God was merely stooping to accommodate his people’s culturally conditioned views of him as an ANE warrior deity. Nothing about this case is affected by whether or not we grant that certain NT authors implicate God in violence.

In short, it seems to me that Copan’s critique is to a large degree predicated on the assumption that an altogether non-violent understanding of God was the lynchpin of my entire case. I do not deny it is important, but it’s not all-important. For the case I make for the cruciform hermeneutic and the Cruciform Thesis remain strong even without it.

Photo on Visual Hunt

Category: General

Tags: Crucifixion of the Warrior God, Cruciform Theology, Paul Copan

Topics: Interpreting Violent Pictures and Troubling Behaviors

Related Reading

Atonement: What is the Christus Victor View?

Most western Christians today understand the atonement as a sort of legal-transaction that took place between the Father and the Son that got humanity “off the hook.” The legal-transaction scenario goes something like this: God’s holiness demands that all sin be punished, which in turn requires that sinners go to eternal hell. The trouble is,…

Challenging the Assumptions of Classical Theism

What came to be known as the classical view of God’s nature has shaped the common, traditional way that most people think about God. It is based in the logic borrowed, mostly unconsciously, from a major strand within Hellenistic philosophy. In sharp contrast to ancient Israelites, whose conception of God was entirely based on their…

A Cruciform Magic Eye

In this post I’d like to share the story of how I came upon the thesis I’m defending in the book I’ve been working on for the last four years entitled The Crucifixion of the Warrior God: A Cruciform Theological Interpretation of the Old Testament’s Violent Divine Portraits. It’s a much longer post than usual,…

When God Abandoned God

On the cross, Jesus’ cried out, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” – which means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? (Mt. 27:46). These are arguably the most shocking, beautiful, and profoundly revelatory words found in Scripture. The cry reveals that on Calvary, the all-holy Son of God experienced God-forsakenness as he bore the…

One Word

While I’ve lately been pretty distracted finishing up Benefit of the Doubt (Baker, 2013), my goal is to sprinkle in posts that comment on the distinctive commitments of ReKnew a couple of times a week. I’m presently sharing some thoughts on the second conviction of ReKnew, which is that Jesus Christ is the full and…

Not the God You Were Expecting

Thomas Hawk via Compfight Micah J. Murray posted a reflection today titled The God Who Bleeds. In contrast to Mark Driscoll’s “Pride Fighter,” this God allowed himself to get beat up and killed while all his closest friends ran and hid and denied they even knew him. What kind of a God does this? The kind…