We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

What Motivates Torture “In Jesus’ Name”?

Why has the church, at times, tortured and murdered people? What motivates killing and persecution “in the name of Jesus” or “for the glory of God”? (See the post from yesterday about how the church has tortured people.) A variety of political, social, and theological explanations could be offered, and they might all be valid. But the core motivation for this barbarism is the same as it is for all other forms of barbarism: idolatry.

This idolatry surfaced when Christian leaders derived some element of their core worth from the rightness of their beliefs—along with, no doubt, the value of their nationalism, the prestige of their positions, the luxury of their wealth and the power of their offices. Whatever affirmed, protected and advanced these idols was judged “good,” while whatever negated, threatened, or hindered these idols was judged “evil.” And since the stakes are often eternally high in religious idolatry, it seemed obvious to these leaders that they needed to glorify God by exterminating their enemies—Christ’s teachings about blessings and doing good to them notwithstanding.

As church history clearly demonstrates, unless self-sacrificial love is made the all-important doctrine that teaches us how to hold all of the rest of our orthodox beliefs, being orthodox provides no more protection against idolatry, judgment, and violence than does being unorthodox. This, again, simply illustrates the point that the Kingdom cannot be identified merely with orthodox religion, or any religion.

Jesus exposed this idolatry in a parable about a Pharisee and a tax collector at the temple (Lk 18:10-14). A Pharisee was inside the temple praying. He thanked God that he was “not like other people—robbers, evildoers, adulterers”—or like a certain tax collector standing outside the temple. In contrast to these sinners, the Pharisee reminded God that he fasted “twice a week” and gave “a tenth” of his income to the temple.

On the other hand, a tax collector stood outside the temple. He didn’t think himself worthy enough to even go inside. In fact, he didn’t even dare lift his face toward heaven when he prayed. He merely “beat his breast” and muttered, “God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

Jesus said that the tax collector rather than the Pharisee “went home justified before God.” And so it will be, Jesus concludes, that “all those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.”

The “holiness” of the Pharisee was a religious “holiness” that exalted itself by contrasting itself with others. The Pharisee—and this epitomizes all idolatrous religion—tried to ascribe worth to himself by detracting worth from others and by feeling special before God on this basis.

Religious idolaters have a pharisaical “holiness” that’s rooted in how they contrast with others. Jesus, on the other hand, manifested a holiness that was compatible with his deep identification with “sinners,” a holiness that was rooted in the life of God that embraces all others. It’s little wonder, therefore, that prostitutes, tax collectors, and other sinners steered clear of Pharisees and other religious leaders, but gravitated to Jesus.

Far from feeling like they received worth from religious leaders, tax collectors and prostitutes rightly sensed that they lost worth around them. Far form being fed life, these sorts of sinners felt they were used as a source of life for these people. In other words, these sinners felt judged.

How different things were around Jesus. Clearly, prostitutes and tax collectors knew this holy rabbi didn’t condone their sinful behavior, any more than he condoned the behavior of robbers, evildoers, and adulterers. Yet, Jesus didn’t get life from the fact that he wasn’t like them. This wasn’t his “holiness.” He didn’t need to get life by contrasting himself with others. He didn’t need the cheap, parasitic “holiness” of religion.

This is also why Jesus was free to love and serve people as they were. Because he didn’t need to derive worth from others, Jesus was free to ascribe unsurpassable worth to others. Again, this begins to explain why prostitutes and tax collectors wanted to hang out with him.

This is the unique and beautiful holiness of the Kingdom, and it contrasts with the ugly “holiness” of religion in the strongest possible way.

Category: General

Tags: Holiness, Humility, Idolatry, Judgment, Kingdom Living, Love, Religious Idolatry, Torture

Topics: Following Jesus

Related Reading

If Judgment is the Opposite of Love, How Can God Judge? (podcast)

Greg considers how God’s judgment differs from our own, making it an expression of his love. Whereas, for us, judgment stands contrary to our love. Episode 488 http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0488.mp3

Becoming Like the Accuser

When the Adam and Eve yielded to Satan and surrendered their God-given authority over the earth and animal kingdom (Gen 3), Satan became “the god of this world” (2 Cor. 4:4), the “ruler of the world” (Jn. 12:32; 14:31) and the “principality and power of the air” (Eph. 2:2) who “has power over the whole…

The Kind of Sin Jesus Publicly Exposes

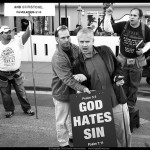

Image by danny.hammontree via Flickr Religious sin is the only sin Jesus publicly confronted. The religious variety of the forbidden fruit is the most addictive and deceptive variety. Instead of acknowledging that judging others is prohibited, religious idolatry embraces the knowledge of good and evil as divinely sanctioned and mandated. It gives the illusion of being on…

How God Changes the World

All who place their trust in Jesus look forward to a day when he will return and fully establish the kingdom of God. When this happens, Scripture promises that everything will change. There will be no more sickness, death, hunger, natural disasters, violence, fear, heartaches, sin, or evil. There will be no more racism, nationalism,…

Participating in the Divine Nature (Love)

When God created the world, it obviously wasn’t to finally have someone to love, for God already had this, within himself. Rather God created the world to express the love he is and invite others in on this love. This purpose is most beautifully expressed in Jesus’ prayer in John 17. Jesus prays to his…

A Lesson in Otherness

http://youtu.be/VeK759FF84s Long, long ago, a third grade teacher taught her class a lesson they will never forget. You won’t forget it either. This video is nearly 15 minutes long, but it’s so worth your time. Let’s love one another.