We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Early Anabaptists and the Centrality of Christ

In a previous post, I wrote about the Christocentric interpretation of the Scriptures espoused by the magisterial Reformers, specifically Luther and Calvin. Their hermeneutic was focused on the work and the offices of Christ, but in my opinion the Anabaptists surpasses their approach because it focused on the person of Christ with an unparalleled emphasis on the call to obey his teachings and follow his example.

In addition, because Luther and Calvin remained within the Constantinian ecclesial paradigm, and thus assumed a just-war perspective on the use of violence, they failed to appreciate the centrality of the enemy-loving non-violence in Jesus’ kingdom ethic. They thus failed to appreciate the full depth of the tension between the Christ who was at the center of their hermeneutic, on the one hand, and OT’s violent divine portraits and violent moral codes, on the other. By contrast, the distinctive emphasis on the enemy-loving, non-violence of Jesus’ teaching and example gave the Christocentric hermeneutic of the Anabaptists a sharper edge as it highlighted the difference between the Old and New Testaments on the use of violence.

I argue that Christ was actually a more significant controlling principle in the Anabaptist hermeneutic and theology than in Luther and Calvin. As Kassen notes, because “Christ was…the center of Scripture” for Anabaptists, “[a]ny specific word in the Bible stands or falls depending upon whether it agrees with Jesus Christ or not.” Hence, “[a]nything which stands in opposition to Christ’s word and life is not God’s word for Christians even if it is in the Bible.” [1] While Anabaptists were as unwavering in their commitment to the plenary inspiration of Scripture as were the magisterial Reformers, they did not hesitate to state that aspects of the OT reflected an incomplete revelation and were no longer binding on Christians.

Another aspect of the Anabaptist approach to Scripture that set them apart was their “hermeneutics of obedience.” The Anabaptists held that understanding and a willingness to obey are closely related. We might compare the way the Bible functioned within the Anabaptist hermeneutic to a Rorschach test: what one discerns when they look at Scripture reflects the condition of their heart at least as much as it reflects what is actually in Scripture.

This conviction, which I introduce here, was by no means an Anabaptist innovation. It’s deeply rooted in Scripture, and one finds it reflected in a variety of ways throughout the Church tradition. What was distinctive about the Anabaptists’ use of this insight, however—and what set them at odds with their Protestant and Catholic contemporaries—was that this insight was fused with their distinctive emphasis on the importance of obeying the teachings and example of Jesus. Some Anabaptists thus insinuated that the reason magisterial church leaders failed to see the centrality of non-violence in Jesus’ teaching and example was not because it is objectively ambiguous but because it’s impossible to correctly interpret Scripture unless one is willing to obey it.

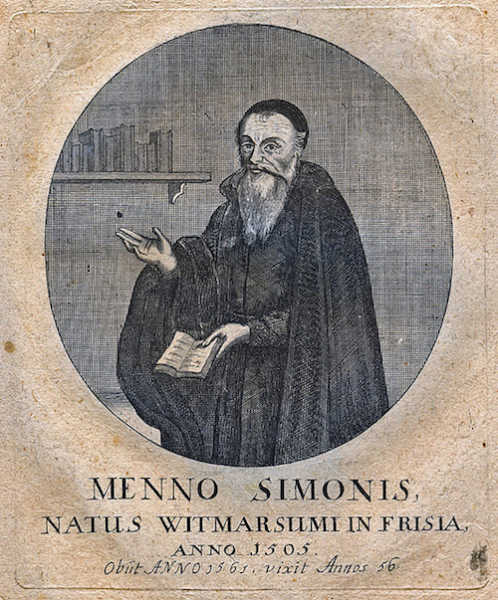

One final aspect of the Christocentric hermeneutic of Anabaptists should be noted. While they were notoriously literalistic when it came to interpreting the NT, there is some evidence that Menno Simons and possibly other Anabaptists were beginning to pick up Origen’s project of reinterpreting or “spiritualizing” aspects of the OT that seemed to contradict the revelation of Christ. Unfortunately, because virtually all of the educated leaders of this fledgling movement were executed before it got off the ground, a distinctly Anabaptist theological reinterpretation of the OT was never explored. We of course cannot say where things might have gone had these leaders survived and/or had a tradition of rigorous theological wrestling with Scripture been established within this movement. Yet, when we consider the centrality of Christ and of non-violence in this movement, together with the fact that some openly acknowledged the contradiction between Christ’s kingdom ethic and aspects of the OT, it doesn’t seem entirely unreasonable to speculate that this group might very well have continued to explore a reinterpretation approach to the problem of violence in the OT, had circumstances allowed for it.

In any event, what I argue in Crucifixion of the Warrior God could justifiably be understood as an attempt to recover and build upon not only the reinterpretation approach of Origen and other early church fathers that was aborted in the fifth century, but also upon the aborted trajectory of early Anabaptists thinking on this problem as well.

[1] W. Klassen, “Bern Debate of 1558: Christ the Center of Scripture,” W. Swartley, ed. Essays on Biblical Interpretation: Anabaptist-Mennonite Perspectives (Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 1984), 106-114 [111].

Photo credit: Stifts- och landsbiblioteket i Skara via Visualhunt.com / CC BY

Category: General

Tags: Anabaptists, Cruciform Theology, Menno Simons

Topics: Biblical Interpretation

Related Reading

Cross Centered Q&A

For those within driving distance of Saint Paul, MN, we invite you to join us for a free event. Greg will be discussing his new book Crucifixion of the Warrior God with Bruxy Cavey (Pastor of The Meeting House in Toronto) and Dennis Edwards (Pastor of Sanctuary Covenant Church in Minneapolis). Don’t miss this opportunity to hear Greg…

Does Paul Condone Vindictive Psalms? A Response to Paul Copan (#1)

In a recent paper delivered at the Evangelical Theological Society, Paul Copan raised a number of objections against my book, Crucifixion of the Warrior of God. This is the first of several blogs in which I will respond to this paper. (By the way, Paul and I had a friendly two-session debate on Justin Brierley’s…

Podcast: How Does God’s Wrath Fit within a Cruciform Theology?

Greg considers God’s wrath. http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0390.mp3

Christ-Centered or Cross-Centered?

The Christocentric Movement Thanks largely to the work of Karl Barth, we have over the last half-century witnessed an increasing number of theologians advocating some form of a Christ-centered (or, to use a fancier theological term, a “Christocentric”) theology. Never has this Christocentric clamor a been louder than right now. There are a plethora of…

Why a “Christocentric” View of God is Inadequate: God’s Self-Portrait, Part 5

I’m currently working through a series of blogs that will flesh out the theology of the ReKnew Manifesto, and I’m starting with our picture of God, since it is the foundation of everything else. So far I’ve established that Jesus is the one true portrait of God (See: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4).…

Crucifixion of the Warrior God Update

Well, I’m happy to announce that Crucifixion of the Warrior God is now available for pre-order on Amazon! Like many of you, I found that the clearer I got about the non-violent, self-sacrificial, enemy-embracing love of God revealed in Christ, the more disturbed I became over those portraits of God in the Old Testament that…