We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

Two Ancient (and Modern) Motivations for Ascribing Exhaustively Definite Foreknowledge to God

A historic overview and critical assessment

Abstract: The traditional Christian view that God foreknows the future exclusively in terms of what will and will not come to pass is partially rooted in two ancient Hellenistic philosophical assumptions. Hellenistic philosophers universally assumed that propositions asserting’ x will occur’ contradict propositions asserting’ x will not occur’ and generally assumed that the gods lose significant providential advantage if they know the future partly as a domain of possibilities rather than exclusively in terms of what will and will not occur. Both assumptions continue to influence people in the direction of the traditional understanding of God’s knowledge of the future. In this essay I argue that the first assumption is unnecessary and the second largely misguided.

While there are a host of factors that motivate Christians to conclude that God possesses exhaustively definite foreknowledge (EDF), three clearly seem more fundamental than others.’ The first is exegetical: Christians who embrace EDF believe it is taught, or at least implied, in scripture. The second is philosophical: Christians who embrace EDF assume that propositions about what ‘will’ come to pass contradict propositions about what ‘will not’ come to pass. Thus, propositions about what ‘will’ or ‘will not’ come to pass exhaustively describe the future: either ‘x will happen’ or’ x will not happen’. Since all grant that God is perfect and must therefore know reality perfectly, it follows that God must know the future exclusively in terms of what will or will not come to pass. In other words, there can be no ‘maybes’ for a perfect, omniscient being like God.

A third motivation that leads Christians to embrace EDF is theological: Christians who embrace EDF generally assume that a God who foreknows with certainty all that will and will not come to pass exercises significantly more providential control than a God who does not. If God does not exhaustively foreknow the future as a domain of settled facts, it is often argued, he cannot guarantee that’ all things work together for the better’ and that all events will fit into a divine plan (Romans 8.28; Ephesians 1.11). Many find this consequence not only exegetically problematic but also existentially unacceptable.

In this essay I will briefly review and critically assess the second and third of these motivations. 2 I will argue that both motivations are rooted in several philosophical assumptions that played a significant role in pre-Christian Hellenistic philosophical discussions about divine foreknowledge, fate, and moral responsibility and that were eventually appropriated by Christian theology. 3 I will first review and critique the philosophical motivation for ascribing EDF to God and then turn to the theological motivation for ascribing EDF to God.

The philosophical motivation Five ancient views on the truth-value of propositions about future contingents Central to the ancient Graeco-Roman debate about divine foreknowledge, fate, and moral responsibility was the question of the truth-value of propositions about future contingents (PFCs). Ancient perspectives on this question can be loosely grouped into five trajectories of thought (the last three of which, we shall see, are not mutually exclusive).

(1) Chyrissipus and other Stoics argued that, since all propositions must be either true or false, all PFCs must be either true or false. In other words, the principle of bivalence applies to PFCs. 4 On this (and other) grounds Stoics generally concluded that it is impossible for the future to be other than it will be. Whatever will be will certainly be. The whole of the future, therefore, is fated and predetermined.5

(2) Epicurus and his followers wanted to avoid determinism at all costs, primarily because they believed it undermined moral responsibility. We are only responsible for our actions if our actions are ‘up to us’ (eph hemin), and they can only be so if the future is not exhaustively settled. 6 Hence these thinkers denied that bivalence applied to PFCs. PFCs are neither true nor false until free agents resolve their truth-value one way or another by making morally responsible choices.7

While most non-Stoic thinkers in the ancient world wanted to avoid Stoic-type determinism, most felt that denying the universal applicability of bivalence was too high a price to pay to accomplish this. Not only did this seem counterintuitive, but the denial of bivalence to PFCs also seemed to undermine divination (which, we shall see, was almost universally accepted) and became associated with the infamously indefensible Epicurean postulation of a random ‘swerve’ among atoms.8 The remaining three views were born out of attempts to avoid determinism while affirming bivalence applies to PFCs.

(3) The first of these final three trajectories of thought was generated by Carneades when he in effect separated the a/ethic status of PFCs from the ontology of the future itself.9 He argued that the fact that PFCs are eternally true or false is not incompatible with the future being ontologically open such that what ends up coming to pass is to some extent up to our free decisions. For Carneades, ‘x will happen at t*’ is true at t just in case ‘x is happening’ is true at t*’.

(4) A fourth and much more complicated trajectory of thought goes back to Aristotle’s famous discussion of a ‘sea battle’ in chapter 9 of On Interpretation.’10 While the dominant interpretation of this passage among contemporary scholars holds that Aristotle was denying that bivalence applies to PFCs, the dominant interpretation in the ancient world was that Aristotle affirmed that PFCs were either true or false but denied they were true or false in a definite way.11 For example, in his commentary on Aristotle’s De Interpretatione, Ammonius writes,

[Aristotle] simply says that singular propositions concerning the future divide truth and falsity, but not in the same way as propositions concerning the present or the past. for it is not yet possible to say which of them will be true and which will be false in a definite way (orismenos), since before its occurring the thing can occur and not occur.12

As with many others ancients, Ammonius shared the Epicurean fear that if the future was settled in a definite way, it would destroy moral responsibility and undermine providence.13 Yet, as with most non-Epicureans, it appears Ammonius also did not want to abandon the universal applicability of bivalence.14

Unfortunately, none of those who used Aristotle’s concept of indefinite truth to retain universal bivalence while avoiding an exhaustively predefined future (e.g. Alconius, Proclus, Ammonius and Boethius) spell out precisely what they mean by it. Mario Mignucci argues that the concept of indefinite truth in these authors simply refers to ‘a contingent proposition, i.e. a proposition which denotes an event whose outcome is not yet settled, and at the same time is a simply true proposition’.15 Mignucci rightly notes that this entails that ‘the relation between propositions and facts is not a temporal relation’. 16 The truth-value of PFCs, in other words, is atemporal. The future could therefore be viewed as ontologically (not just epistemologically) unsettled, and yet bivalence still applied to PFCs. By contrast, Alexander of Aphrodisias and others who interpreted Aristotle’s concept of indefinite truth to constitute a denial of the applicability of bivalence to PFCs held that ‘truth is a totally temporal notion ‘.17 PFCs are indefinite in that they are neither true nor false until free agents resolve them one way or another.

While Mignucci’s assessment of the understanding of indefinite truth in the dominant school of thought represented by Ammonius may be correct, I do not see that it renders the concept coherent. There is no difficulty understanding what someone like Alexander of Aphrodisias who (on most accounts) denied that bivalence applies to PFCs meant by claiming the truth-value of PFCs was indefinite. But what does it mean to say that the truth-value of PFCs is indefinite for those who continue to affirm that PFCs are either true or false? One could of course say their truth-value is indefinite to us, but as Mignucci himself argues, it seems quite clear that Ammonius, Proclus, and Boethius are claiming more than this.18 Rather, they are trying to avoid Stoic determinism and preserve moral responsibility by denying that the future is ontologically settled. Their concept of indefinite truth was their way of doing this while also retaining the universal applicable of bivalence. But, so far as I can see, their attempt was simply unsuccessful.

(5) Closely related to this fourth trajectory is a strand of thought that took Carneades’ distinction between the alethic status of PFCs and the ontology of the future as well as the distinction between definite and indefinite truth and applied them in an innovative, theologically motivated way. A question that Iamblichus, Ammonius, Proclus, and Boethius each wrestled with was: How can God (and/ or the gods) who (they assumed) is altogether necessary, unchanging and atemporal, perfectly know a world that is contingent, perpetually changing and temporal? They answered this question by postulating that divine knowledge must be understood not in terms of the nature of what is known but in terms of the nature of the knower.19 This view, I would argue, is influenced by a widespread ancient misunderstanding, virtually canonized by Plato, which held that perception involves an active process in which light goes out from our eyes. 20 As perception and knowledge were closely linked in the ancient Hellenic world, knowing also was construed as a process of acting on the objects of cognition rather than being acted on by them.21

This activist view of perception and knowledge allowed these thinkers to conelude that the mode of God’s! the gods’ perception and knowledge of the contingent, changing world is defined by the necessary, timeless and unchanging nature of God/the gods, rather than by the contingent, temporal changing world that is seen and known. Hence, they were able to assert that God/the gods see and know changing reality in an unchanging way, the indefinite future in a definite way, the contingent future in a necessary way, and ultimately all of time in a nontemporal way. In this way Iamblichus, Ammonius, Proclus, and Boethius were able to reconcile God’s EDF (which, given God’s atemporality, is only ‘foreknowledge’ from our perspective) with an ontologically open future and thus with moral responsibility.

Largely through the influence of Augustine and especially Boethius, the view that God’s knowledge conforms to God’s timeless mode of being rather than the temporal world that God knows quickly established itself as the dominant view in the Christian tradition. 22 In a variety of forms, the assumption that God’s knowledge is conditioned exclusively by the mode of the divine being rather than the nature of what is known continues to be dominant, as is evidenced, for example, by the fact that the debate over the open view of the future continues to usually be construed as a debate about the perfection of God’s knowledge rather than as a debate about the content of reality that (all orthodox Christians within this debate agree) God perfectly knows. 23

An unnoticed assumption

There are, of course, an abundance of complex, hotly debated issues that surround the traditional Christian view. For example, is it coherent to affirm that God timelessly knows temporal contingencies without His timeless knowledge being conditioned by the temporal contingencies He knows? Why think that a being who lacks any before or after, existing in a single eternal moment, is more perfect than a being who experiences a ‘before’ and’ after’, especially if it is granted that this perfect being is personal and interactive with agents in history? Is the concept of an atemporal eternity even coherent? Could an atemporal God know what time it is now? And, of course, is God’s a temporal mode of knowledge logically compatible with libertarian free will?

The literature discussing these and a host of related questions is voluminous and it would take us far outside the limited scope of this present essay to even begin to discuss them.24 For the purposes of this present essay, I want to instead draw our attention to an unnoticed assumption that historically was a significant driving force in the origination of all five ancient views, including the dominant Neoplatonist and Christian view.

In a word, each of the five views proceed on the assumption that propositions asserting ‘x will occur at t1’ logically contradict propositions asserting ‘x will not occur at t1.’ 25 Since they are contradictory, the two propositions exhaust the alternatives. Hence, one must be true and the other false or bivalence must be deemed inapplicable to PFCs. The assumption thereby seemingly forces one either to accept Stoic determinism, or the Epicurean denial of bivalence, or one or more of the three positions that attempt to steer a middle course between these two views.

While the assumption that ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ propositions contradict each other may seem obvious, there is no strictly logical reason to accept this. Consider: If ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ propositions are logically contradictory and exhaust the alternatives, what are we to make of propositions that assert what ‘might’ and ‘might not’ occur? If’ xwill occur’ and’ x will not occur’ exhaust the alternatives, ‘x might occur’ and’ x might not occur’ can only be interpreted as merely asserting the logical precondition of propositions asserting what’ will’ and ‘will not’ occur and/or as asserting our ignorance of the truth of both propositions. On this reckoning,’ might’ and’ might not’ cannot mean that it is historically possible (viz. in the actual flow of history) that ‘x might and might not occur’- for, per this assumption, either’ x will’ or’ x will not’ occur.

That is to say, ‘might’ and ‘might not’ can never be the final thing to be said about any possible future state of affairs, for what is also true – and eternally true – about any possible future state of affairs is that it either it will or will not come to pass. Hence an omniscient God must eternally know whether the state of affairs will or will not come to pass, never that it might and might not come to pass. From a strictly logical perspective, however, there is no necessity to this restricted interpretation of ‘might’ and ‘might not’. That is, there is no logical basis for denying that the future could be onto logically open.

One might of course offer empirical arguments to the effect that the future is exhaustively definable by ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ type propositions. The Stoics, for example, based their deterministic view primarily on alleged evidence from divination, combined with arguments premised on the universality of causation (deterministically understood).26 So too, if one has other reasons for believing that God possess EDF, then these constitute grounds for interpreting ‘might’ and ‘might-not’ type propositions as expressing merely the logical precondition for ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ type propositions and/or as expressing our ignorance of the truth value of ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ type propositions.27 What is interesting, however, is that the four non-Stoic positions reviewed above do not generally argue in this fashion. They simply assume ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ type propositions exhaust the field and then try to argue that this does not imply determinism. In this sense, this assumption drives all five views and, I believe, lies behind all their problematic features.

An alternative assessment of’ will’ and ‘will not’ type propositions’28

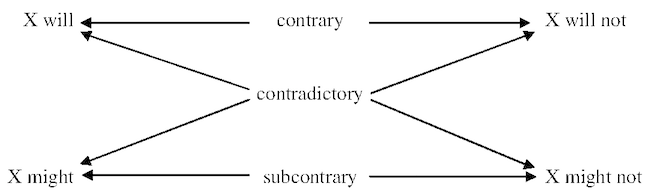

An alternative way of analysing ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ type propositionsand thus, by implication, ‘might’ and ‘might-not’ type propositions-is to understand ‘will’ and ‘will not’ not as contradictories, but as contraries. The contradictory of ‘x will’ is not ‘x will not’, but rather ‘not [x will] ‘ which is logically equivalent to’ x might not’. And the contradictory of’ x will not’ is not ‘x will’ but ‘not [x will not]’, which is logically equivalent to ‘x might.’ On the traditional Aristotelian Square of Opposition, the four possible options with their logical relations appear as follows:

As contraries, ‘will’ and ‘will not’ cannot both be true at the same time, but they can both be false- just in case it happens to be true that’ might’ and’ might not’ are both true at the same time, for sub contraries can, of course, be conjointly true. If’ x might’ is true, then its contradictory’ x will not’ is necessarily false, and if’ x might not’ is true, then its contradictory’ x will’ is necessarily false. (For the subaltern relationship between’ x will’ and ‘x might,’ on the one hand, and ‘x will not’ and’ x might not’, on the other, see the Appendix).

As I read them, this is precisely what Iamblichus, Proclus, Ammonius, and others were groping toward with their vague concept of the indefinite truth of PFCs. Without denying bivalence, they were attempting to affirm something in between ‘will’ and ‘will not’. Unfortunately, their assumption that ‘will’ and ‘will not’ are contradictories rather than contraries prevented them from doing so with logical consistency.

For example, in his commentary on Aristotle’s de Interpretatione g, Ammonius says that what he is asking is ‘whether every contradiction divides truth and falsity in a definite way, or [whether] there is some contradiction which divides them in an indefinite way (aoristos) ‘.29 He answers by asserting that propositions containing future contingents ‘divide … truth and falsity, however not in a definite but [in] an indefinite way’. Unfortunately, Ammonius, like everybody else at the time, was yet considering ‘will’ and ‘will not’ as contradictories rather than contraries, as is clear from his very next sentence: ‘It is necessary that Socrates tomorrow either will or will not bathe and it is not possible that both or neither are true.’30

I suggest that what Ammonius wants- and what the concept of ‘indefinite truth’ is trying to provide – is a way both to affirm for the sake of bivalence, and to deny for the sake of morally responsible free will, that it is settled that Socrates will or will not bathe tomorrow. Unfortunately, by applying bivalence to ‘will’ and ‘will not’ rather than ‘will’ and ‘might not,’ on the one hand, and ‘will not’ and ‘might,’ on the other, neither Ammonius nor anyone else who reflected along these lines could carve out a logical space to consistently have it both ways.

Once we reject the assumption that ‘will’ and ‘will not’ are contradictory and thus exhaust the alternatives regarding PFCs, we can see that there are three, not just two, possible states of affairs regarding the future: ‘will,’ ‘will not’, and ‘might and might not’. As Tom Belt, Alan Rhoda, and I have demonstrated elsewhere, when its contrary, sub contrary, and subaltern relationships are illustrated, the traditional Square of Opposition is transformed into a hexagon of logical relations (comprised of three versions of the original Aristotelian square, as illustrated in the Appendix).

Positing a threefold rather than a twofold analysis of possible states of the future allows us to avoid Stoic determinism, but without having to bite the counterintuitive Epicurean bullet of denying bivalence. Regarding all PFCs, we can affirm that either a proposition or its contradictory is true. That is, either’ x will occur’ or ‘x might not occur’; either ‘x will not occur’ or ‘x might occur’; and either ‘x might and might not occur’ or ‘x will or will not occur’. This also allows us to avoid determinism without having to accept the various philosophical conundrums associated with views (3)-(5).

What this means for omniscience

This analysis obviously has important ramifications for our understanding of the content of God’s knowledge. For if we grant that ‘might’ and ‘might-not’ type propositions may be conjointly true- and thus that ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ type propositions may be conjointly false- then an omniscient being would perfectly know the future in terms of what may and may not come to pass to the extent that the future is comprised of historically (not just logically) possible future events, and would perfectly know the future in terms of what will or will not come to pass to the extent that the future is comprised of events that in fact will (certainly) or will not (certainly) come to pass. The truth-value of propositions about what may and may not come to pass obviously changes if and when circumstances that once made a future event merely possible now make it certain to occur or not, and an omniscient God would, of course, instantly know when this shift occurred. 31

The issue of the precise extent to which the future is at any given time ‘open’- i.e. comprised of’ might and might-not’ historical possibilities- and the extent to which it is at any given time settled- i.e. comprised of’ will’ or’ will-not’ settled facts- is one that could only be inferred by humans on empirical, not logical, grounds. What is important, however, is that once one accepts that propositions asserting what ‘will’ and ‘will not’ occur are contraries, not contradictories, it can no longer be held hat omniscience means, by definition, that God possesses EDF. Consequently, there is no longer any difficulty asserting that God is omniscient and affirming the universal applicability of bivalence while at the same time denying that the future is exhaustively settled.

The theological motivation

We turn now to the theological motivation for ascribing EDF to God. If God does not know the future exhaustively as a realm of settled facts, does this not significantly undermine his providential control of the world?

Foreknowledge and providence in the Ancient World

As with the philosophical motivation, the theological motivation for ascribing EDF to God did not originate with Christianity. To the contrary, the association of foreknowledge with providential assurance was a central aspect of the Hellenistic debate over the issue of divine foreknowledge, fate, and moral responsibility. The debate largely centred around the practice of divination which was part of the social fabric of Graeco-Roman culture. As Luther Martin notes, divination and other practices ‘established and maintained the structure of [Hellenistic] society’. 32 ‘The social identity of Greece’, he continues, ‘was commemorated at its oracular shrines with their pan-Hellenic framework of cosmic fate and their practices of divination, a practice which continued to exemplify popular piety until the establishment of Christianity, and beyond’. 33 While divination was occasionally ridiculed by certain sceptical philosophers (e.g. Carneades and Cicero), it was almost universally accepted by academics and lay people alike and was widely regarded as the main proof that the gods were concerned with and involved in human affairs.34 Indeed, the alleged success of divination played a central role in the Stoic argument that God’s providential hand governs all things, determining the whole of the future. 35

As we noted above, one of the primary reasons few accepted the Epicurean open view of the future was that, not only did it require the counterintuitive rejection of bivalence, but it was believed to contradict divination and therefore undermine divine providence.36 And this undermining of providence understandably put fear in the hearts of many ancient Greeks and Romans, just as it seems to do for many people today. So highly was divination esteemed that, with very few exceptions, even many of those who espoused an open future (including the Christian Calcidius !) were at pains to show how their philosophies could account for its success and therefore provide an adequate account of divine providence.37

This association of divination with providential security was widely adopted by the early Church. To be sure, early orthodox Christians uniformly reject divination practices and, at least up until Augustine, vigorously attacked all forms of determinism. Yet the association of providence with the conviction that God knows the future exclusively in terms of what will and will not come to pass was almost uniformly adopted from the start. When the early Fathers refer to divine foreknowledge, it is almost always in a context where they are concerned with either proving Christ’s deity from Old Testament prophecies (now understood along the lines of Hellenistic divination- that is, as prognostications) or in contexts where they are discussing God’s providential control of the future. 38

Foreknowledge and providence today

So far as I can see, the widespread Hellenistic assumption that the gods lose significant providential control if they do not know the future as exhaustively settled remains with us to this day. Aside from exegetical objections, the single most frequent criticism raised against the open view in the polemical literature is that it undermines confidence in providence. To illustrate, this criticism permeates Bruce Ware’s book, God’s Lesser Glory. According to Ware, the open view of God posits a ‘limited, passive, hand-wringing God’, who can do little more than hope for the best.39 ‘[W]hat is lost in open theism’, Ware contends,

… is the Christian’s confidence in God …. When we are told that God … can only guess what much of the future will bring … [and] constantly sees his beliefs about the future proved wrong by what in fact transpires …. Can a believer know that God will triumph in the future just as he has promised he will?40

Inasmuch as the need for security strongly influences the faith of most people today, as it did in ancient Greece, this type of argumentation is psychologically effective. But is it valid? I do not believe that it is.

Of course, it cannot be denied that a conception of God who meticulously determines the whole of history, such as we find both in Stoicism and in the classical Augustinian-Calvinist tradition, provides more assurance to believers that everything is going ‘as planned’ than can a God who grants libertarian free will to agents. Most non-Calvinists of course argue that this extra ‘assurance’ is purchased at an unacceptably high price, for it requires, among other things, that we accept all evil as part of God’s providential plan. But more importantly, this is not what is at issue in the debate about God’s foreknowledge. Rather, the issue is over whether God gains any significant providential advantage simply by virtue of knowing the future exhaustively as a domain of settled facts (what will and will not come to pass) as opposed to a domain that includes possibilities (what might and might not come to pass). And the answer to this specific question, I argue, is that He does not, provided one agrees that God possesses unlimited intelligence.41

Of course, we humans are much less in control of a future we know to be comprised of possibilities than we are a future we know to be comprised only of settled facts. But the reason for this is that we only possess a finite amount of intelligence. Hence, the more possibilities we have to anticipate and prepare for, the thinner we have to spread our limited intelligence to anticipate them. This is why playing a formidable opponent in an important game of chess, for example, is much more stressful than (say) working on an assembly line.

By contrast, if God is omniscient, there is no limit to his intelligence. This entails that God does not have a finite amount of intelligence that must be ‘spread thin’ to cover various possibilities. Rather, if God possesses unlimited intelligence, God can attend to each and every one of any number of possibilities as though each and every one was the only possibility- viz. as though each was an absolute certainty.42 For a God of unlimited intelligence, therefore, there is no functional difference between anticipating a possibility and anticipating a certainty. God prepares for ‘maybes’ as effectively as He does ‘certainties’. Indeed, a God of unlimited intelligence anticipates ‘maybes’ as though each was a ‘certainty’. If you ever have the misfortune of playing God at chess, you will most certainly lose. For however you may choose to move, God has been anticipating that very move and preparing a response to it, as though you had to make this move, from the onset of the game- indeed, from before the foundation of the world (for possibilities are eternal, hence eternally known by an omniscient God).

This means that, whatever comes to pass, an open theist can say as confidently as a person who ascribes EDF to God that God had been anticipating this very event from before the foundation of the world, as though the event had to happen.

It is just that the open theist would add that, because God possesses unlimited intelligence, God did not need to foreknow the event as an eternally settled fact in order to anticipate it as though it was an eternally settled fact. Any number of other events could have occurred instead of the event that came to pass, and if any other event had come to pass, the open theist would be saying the exact same thing about it.

In the light of God’s unlimited intelligence, an open theist can affirm that every event happens with a divine purpose without having to assert that everything happens for a divine purpose. God brings an eternally prepared purpose to events, but God does not bring about (or specifically allow) all events for an eternal purpose. The open theist can thus remain as confident as any free will theist who ascribes EDF to God that God can bring good out of evil and fit all events into a divine plan. But she can do so without having to make God complicit in evil.

A question of resources

One might reply that, while a God who possessed unlimited intelligence but lacked EDF could anticipate possibilities as effectively as certainties, He could not be as efficient at utilizing resources in anticipating future events as He could if He possessed EDF. To return to the chess analogy, a God who foreknew with certainty how His opponent was going to move wouldn’t need to expend resources putting contingency plans in place for every possible move His opponent might make. While open theists can believe as strongly as a person who ascribes EDF to God that God has an eternally prepared response for any event that comes to pass, only the person who ascribes EDF to God can further affirm that God has been preparing a response exclusively for this event.

I think the objection must be granted. At the same time, it does not seem to me that the additional providential advantage that EDF gives God is all that significant. Since both views affirm libertarian free will, both must grant that God’s eternally prepared response to events is merely the best possible (or as good as possible just in case there is no uniquely best response possible) given the creational constraints God must work around. Had individuals chosen differently, both views must grant, a more ideal response might have been possible. Indeed, had individuals chosen differently, there might be no event requiring God to respond in the first place. Hence, the difference between free-will theists who affirm EDF and those who deny EDF boils down to a disagreement over the scope of logically possible resources available to God as He prepares his best possible response to future events, given the constraints the kind of world He decided to create place upon him.43

Moreover, since both views affirm the assuredness of God’s ultimate victory, whatever slight providential advantages the EDF perspective might offer us must be considered penultimate. That is, both views confess that God will ingeniously weave all events into a God-glorifying unity under Christ (Ephesians, 1.10), and that, when the eschaton has come, we’ll regard all the sufferings of this present epoch as unworthy of comparison to the joy we then experience (Romans 8.18). Eschatologically speaking, therefore, whatever providential advantages EDF might grant God are trivial.

Yet, for the purpose of this present paper, perhaps the most important reply to the above objection is that this is not the level at which the providential argument against open theism has generally been waged, either in ancient or in modern times. The issue has not been that a God who lacked EDF might merely have a narrower range of logically possible resources to draw from as He prepares the best possible response to future events, but that a God who lacked EDF can’t be providentially assuring at all. As we noted above, many contemporary Christians argue that a God who faces a future partially comprised of possibilities must be a ‘limited, passive, hand-wringing God’ who can only ‘guess at what much of the future will bring’, and whom Christians can’t trust to ‘triumph in the future ‘.44 And in reply to this sort of all-to-common argument, we need only point out that the charge presupposes that God is limited in intelligence. Only a god of limited intelligence would need to foreknow all that comes to pass in order to avoid wringing His hands in worry or in order to be assured of triumphing in the future.

Conclusion

I have argued that both the philosophical and the theological motivations for ascribing EDF to God are derived from, and rooted in, misguided Hellenistic philosophical assumptions that pre-date Christianity. There’s no strictly logical reason why we should not regard ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ propositions as contraries rather than contradictories, and thus no reason to assume ‘will’ and ‘will-not’ propositions exhaustively define the future. Hence, there is no strictly logical reason to deny that the future is partly comprised of events that might and might not occur and that God, being omniscient, therefore knows the future partly as a domain of what might and might not come to pass. Yet, a God of unlimited intelligence does not lose any significant providential advantage because of this fact. Whatever comes to pass, God has been preparing for it from all eternity as though it had to come to pass.

Appendix and Notes:

Appendix: The hexagonic logic of an open future [Adapted from G. Boyd, A. Rhoda, and T. Belt ‘The hexagon of opposition: thinking outside the Aristotelian box’, unpublished manuscript]

Category: Essays

Tags: Essay, Open Theism

Topics: Defending the Open View

Related Reading

The Cruciform Center Part 4: How Revelation Reveals a Cruciform God

I’ve been arguing that, while everything Jesus did and taught revealed God, the character of the God he reveals is most perfectly expressed by his loving sacrifice on the cross. Our theology and our reading of Scripture should therefore not merely be “Christocentric”: it should be “crucicentric.” My claim, which I will attempt to demonstrate…

Greg Boyd Chats with Thomas Jay Oord (podcast)

Greg talks with Thomas Jay Oord about what God can and can’t do. Episode 674 http://traffic.libsyn.com/askgregboyd/Episode_0674.mp3

How do you respond to Jeremiah 1:5

The Lord says to Jeremiah, “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, and before you were born I consecrated you; I appointed you a prophet to the nations.” This verse shows God’s love and plan for Jeremiah before he was born. This does not imply that Jeremiah could not have “rejected God’s…

How do you respond to Matthew 26:36?

At the last supper Jesus said to Peter, “Truly I tell you, this very night, before the cock crows, you will deny me three times.” This is probably the most frequently quoted verse by defenders of the classical understanding of God’s foreknowledge against the open view. How, they ask, could Jesus have been certain Peter…

Does God Have a Dark Side?

In the previous post, I argued that we ought to allow the incarnate and crucified Christ to redefine God for us rather than assume we know God ahead of time and then attempt to superimpose this understanding of God onto Christ. When we do this, I’ve argued, we arrive at the understanding that the essence…

How do you respond to Isaiah 53:9?

Speaking of the suffering servant Isaiah says, “[T]hey made his grave with the wicked and his tomb with the rich…” As with most evangelical exegetes, I believe that Isaiah 53 constitutes a beautiful and stunning prophetic look at the person of Jesus Christ. The most impressive feature of this prophecy is that the suffering servant…