We run our website the way we wished the whole internet worked: we provide high quality original content with no ads. We are funded solely by your direct support. Please consider supporting this project.

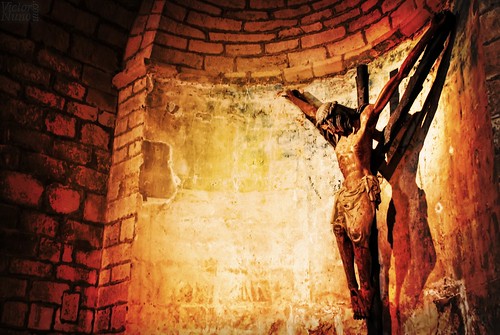

The Cross and the Witness of Violent Portraits of God

In my previous post I noted that the prevalent contemporary evangelical assumption that the only legitimate meaning of a passage of Scripture is the one the author intended is a rather recent, and very secular, innovation in Church history. It was birthed in the post-Enlightenment era (17th -18th centuries) when secular minded scholars began to insist that the Bible must be interpreted the same way we interpret any other book. Prior to this time the Church uniformly taught that, since the ultimate author of Scripture is God, any given passage may have a number of meanings that go beyond what the human author intended. (This “surplus” of divinely-intended meaning is traditionally referred to as the “sensus plenoir” of Scripture).

The precedent for the traditional way of reading Scripture is found in the NT itself, for as I noted in an earlier post, NT authors exhibit little concern for the original meaning of passages in the OT. As is true of all Christian interpreters prior to the Enlightenment, the authors of the NT understood that, if we’re going to see how all Scripture bears witness to Christ, as Jesus himself taught (Jn. 5:39-45; Lk 24: 25-27, 32, 44-46), we have no choice but to allow the Spirit to “remove the veil,” as Paul taught so we can discern a deeper meaning – a more profound “glory” — than what we find in “the letter” of Scripture (2 Cor. 3:6, 14—18). And, consistent with the above mentioned teaching of Jesus, the “glory” Paul is referring to is “God’s glory displayed in the face of Christ” (2 Cor. 4:6, cf. 3:17-18).

NT authors utilize a number of creative strategies to find Christ in the OT, but in this and my previous two posts I’m addressing one that I had never heard of before: namely, “prosopological exegesis.” In his intriguing book The Hermeneutics of the Apostolic Proclamation: The Center of Paul’s Method of Scriptural Interpretation (Baylor University Press, 2012), Matthew Bates goes so far as to argue that this strategy, which he demonstrates was employed throughout the Greco-Roman world, constitutes the very center of Paul’s hermeneutic (that is, his approach to the OT). By positing a different speaker and/or addressee in a sacred text, ancient interpreters were able to overcome difficulties they confronted in their sacred writings and to discern how these writings spoke to their contemporary situation (183, 218).

While Paul and other early Christians used this technique to discern how the OT reflects core aspects of their Christ-centered proclamation, this strategy was often employed whenever there was “ a perceived incompatibility in the mind of the interpreter between the ascribed identity of the speaker/addressee” in a text, on the one hand, “and certain well-known “facts” pertaining to that person,” on the other. Bates argues that, among ancient interpreters, this perceived incompatibility “stimulates the selection of a more suitable prosopon” (216) – that is, a deeper “voice behind the (apparent) voice” of the text.[1] For example, Bates notes that ancient Stoics employed this strategy to get around the morally offensive depictions of the gods in Homer, whom many considered to be divinely inspired (209-10).

Whether or not Bate’s work demonstrates that prosopological exegesis constitutes “the center” of Paul’s hermeneutics, I am convinced it at least demonstrates that Paul’s creative use of this strategy, under the guidance of the Spirit, provides warrant for us to be similarly creative and imaginative as we confront material in the OT that is incompatible with the revelation of God in the crucified Christ. So the question I’ve been wrestling with for the last several weeks is, how might prosopological exegesis help us discern how portraits of Yahweh causing parents to cannibalize their children (e.g. Lev. 26:28-29; Jere 19:9; Ezek.5:10 ) or commanding genocide (Deut. 7:2) point us to the enemy-embracing, non-violent, self-sacrificial love of God revealed on the cross?[2] I submit that, if ever it is true that “the letter kills,” as Paul says (2 Cor. 3:6), it is here! Hence, if ever we need to have “the veil removed” and to employ creative and imaginative strategies under the guidance of the Holy Spirit to search for “the (true) voice behind the (apparent) voice” of the “letter” of passages, it is here!

Moreover, if ever there was a “perceived incompatibility” between the ascribed identity of the speaker” of a passage, on the one hand, “and certain well-known “facts” pertaining to that person,” on the other, it is here! For the “well-known ‘facts’ pertaining to” Yahweh are that he is revealed in Christ to be a God who sacrifices himself to bring abundant life to all, the very opposite of a “thief” who “kills, steals and destroys” (Jn 10:10) by causing parents to eat their babies and by commanding the wholesale slaughter of entire people groups! Hence, if ancient Stoics employed this strategy to explain Homer’s offensive depiction of the gods, might we not be permitted to employ it, under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, to not only explain away offensive depictions of Yahweh, but to discern how they bear witness to the crucified Christ?

Though Bates’ work doesn’t address the issue of the OT’s violent divine portraits, he points us in the direction of an affirmative answer to these questions when he suggests that his work entails that contemporary Christians should follow Paul’s lead and “unabashedly gaze on the ancient Jewish scriptures through the realigning lens of the Christ story….” (353). With this I would wholeheartedly agree, though for reasons I’ve argued elsewhere, I would bring further specificity to the “Christ story” by noting that the entire “Christ story” is thematically centered on the cross. With Moltmann, I contend that “[t]he crucified Christ…[is] the key for all the divine secrets of Christian theology,” including “the key” to disclosing how all Scripture — including its violent portraits of God — bear witness to Christ.[3]

So, how does gazing at violent portraits of God through the lens of the crucified Christ help us discern how they bear witness to the crucified Christ? And how might “prosopological exegesis” play into this? This is what I’ll address in my next post. Stay tuned!

Meanwhile, be assured that when Paul says “be imitators of God” (Eph.5:1), he did not intend us to eat our babies and engage in genocide. He rather means, “live in love, as Christ loved you and gave his life for you” (5:2).

[1] Bates cites as examples Heractlius, Allegoria, 62:1-2; Mk 12:35-37; Acts 2:27; 16:35.

[2] To grasp the gravity of the issue before us, its worth noting that Yahweh is depicted as uttering the command to slaughter the entire population of certain regions thirty-nine times in the OT.

[3] J. Moltmann, J The Crucified God: The Cross and the Criterion and Criticism of Christian Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993 [orig. German, 1973]). 114.

Víctor Nuño via Compfight

Category: Essays

Tags: Bible, Bible Interpretation, Cruciform Theology, Essay, Jesus, New Testament, Old Testament

Topics: Interpreting Violent Pictures and Troubling Behaviors

Related Reading

God in Our Image

zen Sutherland via Compfight We came across this piece written by Jonathan Storment earlier this month and we had to share it here. The title of the piece is Everyday Idolatry: My God. He does a great job of outlining the ways that we twist God into whatever we need him to be to prop up…

What Is God’s Glory?

In John 12 we find a view of God’s glory that challenges many modern notions of what the glory of God means. In this passage, we find that Jesus was “troubled” by the cross that lay ahead to such an extent that he wanted to cry out, “Father, save me.” But Jesus quickly expresses his…

Classical Theism’s Unnecessary Paradoxes

The traditional view of God that is embraced by most—what is called “classical theology”—works from the assumption that God’s essential divine nature is atemporal, immutable, and impassible. The Church Fathers fought to articulate and defend the absolute distinction between the Creator and creation and they did this—in a variety of ways—by defining God’s eternal nature…

Part 3: Disarming Flood’s Inadequate Conception of Biblical Authority

Image by Ex-InTransit via Flickr In this third part of my review of Derek Flood’s Disarming Scripture I will offer a critique of his redefined conception of biblical inspiration and authority. I will begin by having us recall from Part I that Flood holds up “faithful questioning” over “unquestioning obedience” as the kind of faith that Jesus…

Why Did Jesus Die on the Cross?

If asked why Jesus had to die on the cross, most Christians today would immediately answer, “To pay for my sins.” Jesus certainly paid the price for our sins, but it might surprise some reader to learn that this wasn’t the way Christians would answer this question for the first thousand years of Church history.…

Responding to Driscoll’s “Is God a Pacifist?” Part I

I’m sure many of you have read Mark Driscoll’s recent blog titled “Is God a Pacifist?” in which he argues against Christian pacifism. I’ve decided to address this in a series of three posts, not because I think Driscoll’s arguments are particularly noteworthy, but because it provides me with an opportunity to make a case against what I’ve…